Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark: Book Smart, Kids Dumb

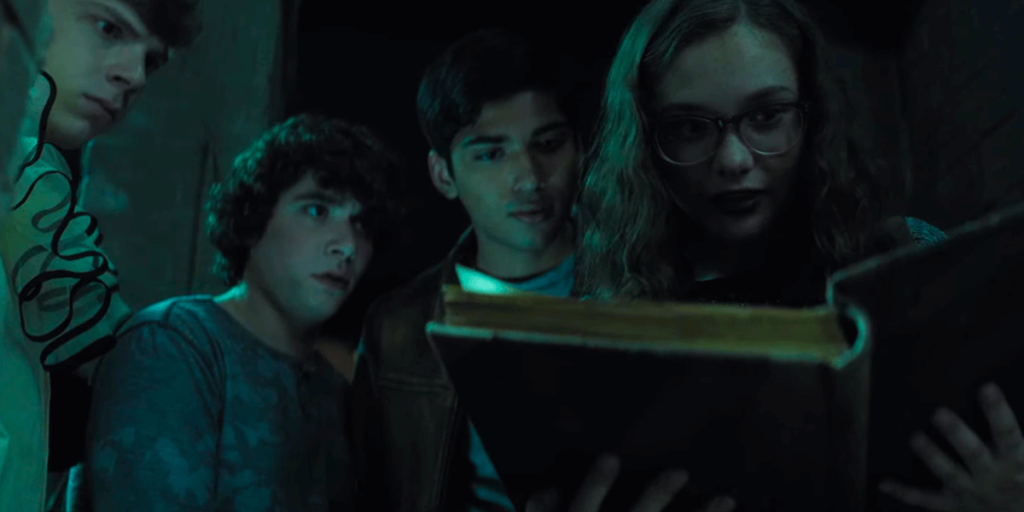

Less teenage horror movie than lightly creepy seminar, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark functions as a kind of starter kit for curious viewers looking to dabble in the cinema of fright. Cogently threading together a handful of spooky tales lifted from Alvin Schwartz’s famous anthology of the same name, this passable imitator assembles the building blocks of classic fear fests, then nudges them into predictable, clockwork motion. It’s nothing we haven’t seen before, which may be why it seems geared toward horror virgins—the innocent few who really haven’t seen this stuff before. As an example of the genre, it’s pedestrian; as an introduction to it, it’s effective.

The director André Øvredal has a keen understanding of the essential elements, which he draws together with workmanlike efficiency. There is a haunted house, complete with creaky hinges, dark closets, and a cavernous basement. There is a cornfield, the rows upon ominous rows of crops lorded over by an ugly, unsmiling scarecrow. There are rusty wheelchairs, slowly turning doorknobs, and long, spindly shadows that emanate from nowhere, stretching menacingly across cobwebbed walls. And then there are the more visible and corporeal terrors: wriggling spiders; reanimated corpses; Richard Nixon. Read More