The Phoenician Scheme: The Hand Grenade’s Tale

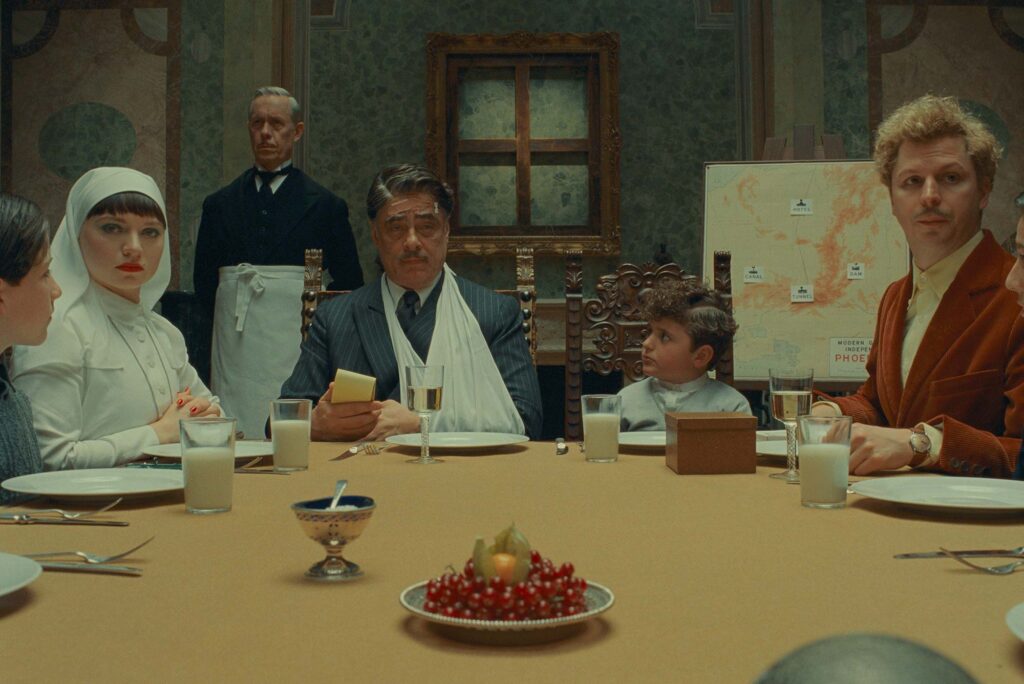

Wes Anderson’s movies are so meticulously constructed, it’s easy to overlook that they also tend to be explosive, messy, and violent. It takes all of 30 seconds into The Phoenician Scheme, his latest lavishly imagined whirligig, before someone gets literally blown in half by a missile. Not long after, the picture’s unscrupulous hero, an entrepreneur named Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro), emerges from the wreckage of a plane crash, trying to stuff a protruding organ back inside his body. Over the picaresque adventure that follows, Korda will face flaming arrows, gun-toting guerillas, duplicitous spies, overcooked pigeons, and a pit of quicksand. He’s the unflappable eye of a fastidiously unstable hurricane.

That all of this mayhem unfolds in the context of Anderson’s characteristic rigor—a method of careful framing, crisp camerawork, and filigreed production design—isn’t really a product of dissonance. Rather, The Phoenician Scheme harmonizes control and commotion. Anderson’s style is often pejoratively deemed fussy, but his exacting craft doesn’t drain the life from his filmmaking. Quite the opposite: The rich colors, the sharp wordplay, and the impeccable ornamentation all coalesce to imbue the proceedings with urgency and vivacity. In this heightened alternate reality, precision generates momentum. Read More