Holiday Gift Bag: Bumblebee

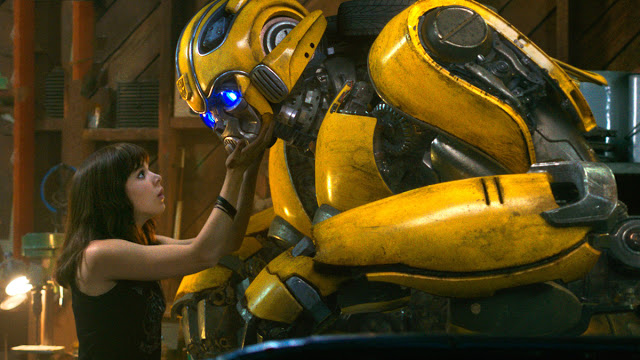

As a girl-and-her-robot story, Bumblebee is genuinely playful and affecting. Sure, Hailee Steinfeld’s Charlie is a walking cliché, tormented both by memories of her dead dad and by the richer, blonder girls who mock her awkwardness and her relative poverty. But Steinfeld brings real depth to the one-dimensional role, especially once she starts sharing her garage—where she toils to repair her father’s old Corvette, thereby establishing her tomboy bona fides—with the titular transformer. With a canary-yellow paint job and glowing blue eyes, Bumblebee proves to be an agile comic partner, whether he’s grooving to the sounds of The Smiths or inadvertently rampaging through Charlie’s home like the dog from Turner & Hooch. Director Travis Knight (Kubo and the Two Strings) has a good handle on social misfits, and he wields some impressive special effects—in addition to those iridescent baby-blues, Bumblebee has metallic flaps that double as puppy-like ears—to make the robot impressively expressive; the computer code becomes a character, one who conveys anxiety, devotion, and fear. His cold steel will warm your heart. Read More