Leave No Trace: Out of the Woods, But Not Fitting In

Every night before they go to sleep, the 13-year-old girl and her father, nestled snugly in a cramped tent, say goodnight to each other without using words. Instead, they make a sort of clicking sound, bringing their tongues against the back of their front teeth, the type of noise one might use to summon a horse: “tchic-tchik.” In other contexts, it might sound silly; here, it’s an expression of sincere, absolute love.

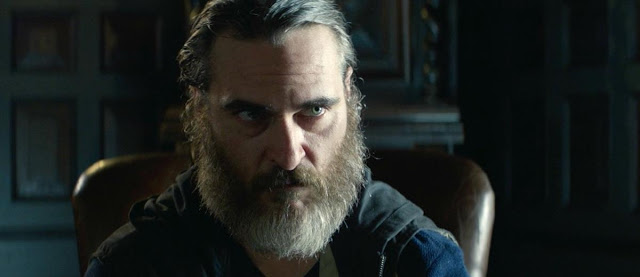

To my recollection, nobody actually says “I love you” in Leave No Trace—the gentle, empathetic, quietly devastating new movie from Debra Granik—but the concept of devotion is nevertheless sewn into the film’s very fabric. It’s present in the relationship between the father, Will (Ben Foster, against type), and the girl, Tom (Thomasin Harcourt McKenzie, revelatory), who open the picture residing comfortably and illegally in the verdant woods outside Portland. It’s found in the respect that the two demonstrate for nature, with all its wonders and terrors. (The title derives from a popular conservationist ethos.) And it’s apparent in the warm regard that Granik displays for her characters, whom she treats with curiosity, tenderness, and honesty. Read More