In the opening scene of Rushmore, a math teacher asks Jason Schwartzman whether he might be able to come to the blackboard and solve an impossibly complex equation. Schwartzman’s character does so effortlessly and receives the adoring congratulations of his classmates, at which point Wes Anderson reveals that the sequence is a dream. Hidden Figures, Theodore Melfi’s sincere and sappy biopic of three black women who worked at NASA during the height of the Space Race, is essentially a feature-length version of this scene, minus the concluding fake-out. It fancies itself a hard-hitting historical drama, but it’s really a frothy, wish-fulfillment fantasy.

And what’s wrong with that? Hidden Figures may not trouble your mind or get under your skin, but it does provide a welcome, feel-good tonic for these troubled times. It insists, with disarming directness, that the evils of prejudice and entrenchment will always succumb to the virtues of hard work and human decency. Its period setting is one of extreme unease (as opposed to now?), but its tone is unabashedly wholesome and reassuring.

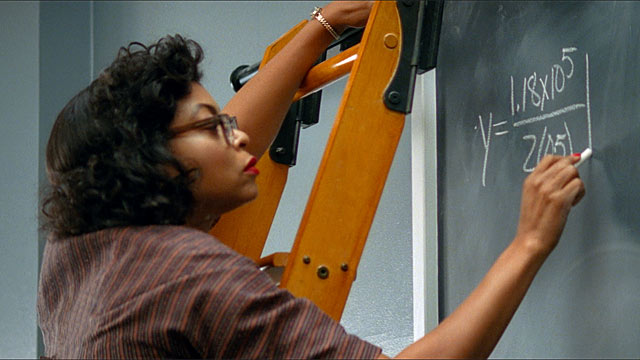

Not that its protagonists would consider themselves stress-free. Hidden Figures’ heroines are all industrious professionals who nevertheless face race-based obstacles to workplace success. Katherine Goble (Taraji P. Henson, very good) is an ingenious mathematician with expertise in analytic geometry, but her white colleagues (including The Big Bang Theory’s Jim Parsons) demean her talents and inundate her with unfulfilling grunt work. Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe, who made her live-action acting debut just a few months ago in Moonlight) is a gifted engineer, but she lacks the required credentials to work on the space shuttle because she is precluded from attending the all-white classes that dispense certification. And Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer) is a de-facto supervisor who, despite overseeing several dozen workers, is treated and paid like an entry-level employee.

In tracing the inevitable arc of this triumvirate—each of whom begins the movie subjugated and ends it triumphant—Hidden Figures is enjoyable, predictable, and largely unexceptional. Yet in adapting the book by Margot Lee Shetterly, Melfi and co-writer Allison Schroeder do impressive work contextualizing their characters’ struggles firmly within 1960s America. NASA may be a locus of technological innovation and human brainpower, but as shown in the film, it is also just another Virginia job site, one that is hardly immune to the rank bigotry that infected the country during the civil rights era. And Hidden Figures, with clarity and insight, depicts the agency’s offices not as KKK-sponsored lairs of outright terror but as places of casual superiority and normative judgment. Throughout, our heroines are constantly reminded of their second-class status, whether it’s being forced to sit at the back of a bus or drink from an inferior coffeepot. In a quietly awful moment that encapsulates their perpetual struggle, Katherine asks where to find the ladies’ room, only to be told, “I have no idea where your bathroom is.”

That’s horrible, but on the whole, Hidden Figures is more uplifting than upsetting. While it illustrates the barricades that society erected to its characters’ professional enrichment, it also shows how they toppled them. In a sense, the movie functions as a how-to manual, an answer key to an especially repellent question: How can individuals who are treated so dismissively by established institutions simultaneously advance within the confines of those institutions? Unable to rebel in traditional ways, Katherine, Mary, and Dorothy must instead rely on stealth and pluck. For Katherine, this means constantly scurrying across NASA’s campus to use the bathroom, accompanied by reams of paperwork and the jaunty original music of Pharrell Williams. Mary, in making her legal argument that she should be allowed to attend racially restricted classes, is forced to appeal to the vanity of the white judge presiding over her case. And Dorothy, fearful of being displaced, resolves to teach herself about the intricacies of the enormous machine that has recently arrived at NASA, an imposing behemoth that goes by the initials I.B.M.

All of this is cleverly and persuasively presented, but in emphasizing its characters’ dilemmas, Hidden Figures often sacrifices nuance in favor of preachy moralizing. This is particularly true in the case of Katherine, whose story is at once the movie’s most entertaining and its least convincing. Despite her formidable intelligence, she is continually disregarded, and Henson plays her with a powerful combination of hardy resolve and fed-up exhaustion. (A scene where she finally erupts in frustration bears an unfortunate resemblance to Lupita Nyong’o’s wrenching “500 pounds of cotton” speech from 12 Years a Slave.) Yet the film’s ultimate solution to her predicament seems to be that, if you’re ever the victim of workplace discrimination, the best thing you can do is work for Kevin Costner.

In a loose, effortless performance, Costner plays Al Harrison, the director of the Space Task Group, whose immediate task is to ensure that the astronaut John Glenn (portrayed with folksy charm by Everybody Wants Some’s Glen Powell) can successfully orbit the earth and return without bursting into flames or crashing into rubble. Al is the kind of gruff superior who is constantly barking out orders and wiping text off chalkboards, but he also appears to be colorblind when it comes to his employees. In a fantastical, undeniably rousing scene, upon learning that Katherine’s segregated bathroom is a half-mile away from her desk, a furious Al takes a sledgehammer to that bathroom’s “Coloreds” sign, and you have to wonder if he’s just metaphorically bludgeoned racism out of existence.

That moment may not be entirely credible, but it is empowering. Yet while Hidden Figures is thematically poignant, it never quite treats its protagonists as actual characters. This is felt most acutely when it comes to Katherine’s love life; her swift courtship by a handsome colonel (Mahershala Ali, underserved) is the embodiment of the token romantic subplot. But Melfi also fails to adequately dramatize the women’s work. Some of this is simply a matter of degree of difficulty—it is quite hard to translate the process of solving equations or calculating sums into stimulating cinema. All the same, Hidden Figures’ representation of intellectual problem-solving lacks real vigor and tangibility. Mathematical theory needn’t feel so theoretical.

Of course, while Hidden Figures is nominally about the Space Race, its technical details are largely beside the point. Instead, its evocation of scientific achievement serves chiefly to provide a backdrop for its emotional drama. (This may explain why the sequences of Glenn in his space shuttle are conceived with a minimalism that borders on neglect.) And that’s fine, because the drama is genuinely stirring. There is no shame in this movie’s goal of telling a didactic, fact-based story that both educates and inspires.

In one of the film’s more striking period touches, Katherine and her cohorts are dubbed “computers”—literally meaning, “one who computes”. And Hidden Figures itself is plainly the product of human engineering. It carefully assembles its components and arranges them pursuant to a familiar formula, the ultimate product of which is the pleasure of its audience. On that score, this movie gets its math right.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.