Us: Meeting the Enemy, and Looking in the Mirror

Jordan Peele’s Get Out was such a unique and exhilarating blend of images and ideas—a suspenseful horror movie with a pointed political message—that it was easy to tolerate its third-act slide into ordinariness. His follow-up, Us, is not quite as thematically bracing; it feels more like a superlative exemplar of nightmare cinema than a full-on reinvention of the form. But even if Us is more entertaining than extraordinary—and to be clear, it would be deeply unfair to demand that Peele’s encore be equally groundbreaking—it is in some ways a more impressive picture than Get Out, with superior visuals and more consistent follow-through. Minimizing sociopolitical allegory in favor of visceral dread, it finds Peele sharpening his focus and refining his technique. He’s less interested in making you look inward in self-reflection than in forcing you to shut your eyes in fear.

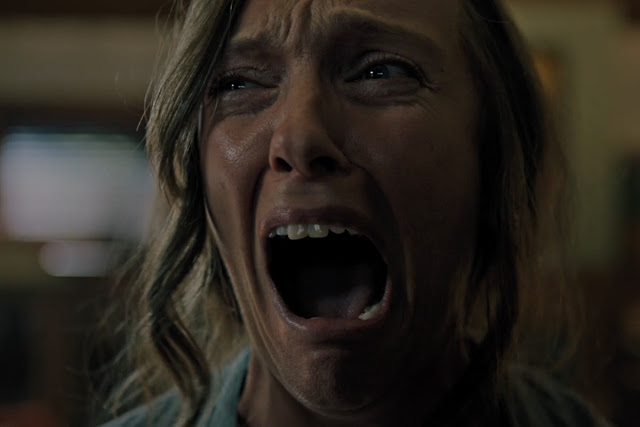

This isn’t to say that Us is altogether silent with respect to race and politics. Its vision of an unseen underclass—a toiling horde of perpetually neglected laborers, à la The Time Machine—isn’t all that far removed from Get Out’s conceit of white aristocrats bidding on black bodies. But the most striking overlap between the two films is their use of the same indelible image: a close-up of a central character’s face, eyes widening in dismay and filling with tears as they perceive the terror of what surrounds them. Read More