Yelena Belova is bored. She’s just elegantly parachuted into a secret laboratory in Kuala Lumpur, swiftly dispatching a crew of anonymous guards before overpowering a hapless scientist so that she can bypass the facility’s facial-recognition security and retrieve… forget it, it doesn’t matter. The point is that she’s done this sort of thing before. To a layman, such strenuous effort may sound exciting, but for Yelena, it’s just another day at the superhero-adjacent office. She needs something fulfilling, something inspiring, something new.

Thunderbolts is the 36th(!) installment in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and the key to its moderate success is its understanding of Yelena’s self-described ennui. The MCU is no longer the global box-office behemoth it once was, in part because there are only so many times self-important men in metallic suits and spandex can save the world from imminent catastrophe. Thunderbolts, directed by Jake Schreier from a screenplay by Eric Pearson and Joanna Calo, is not a great movie; it remains overly reliant on franchise mythology, and its storytelling is a little choppy. But it’s an appealing sit—not just for its welcome lightness of tone, but for its willingness to shift away from standard-issue heroes and toward more colorful, esoteric characters. Specifically, it’s about a bunch of losers.

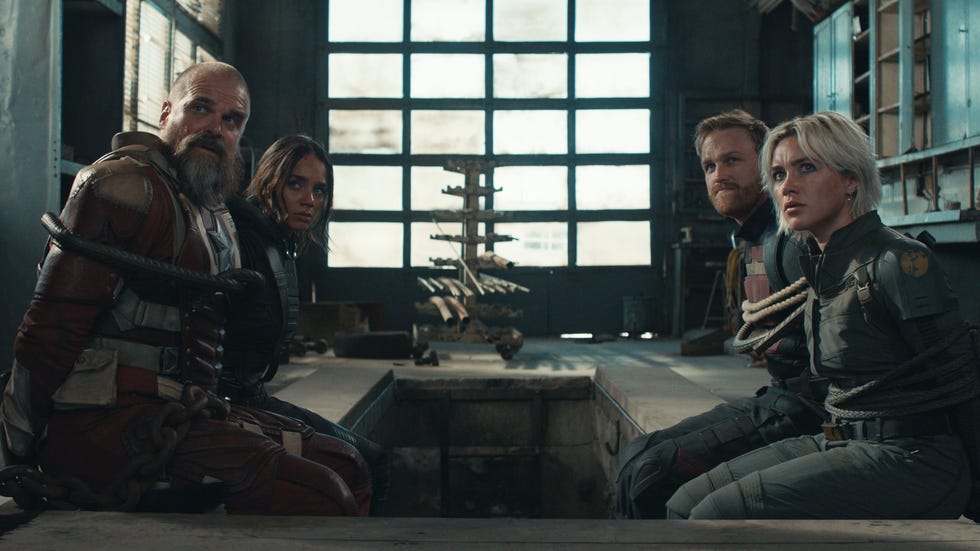

Maybe that’s unfair. Certainly Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan), the Winter Soldier himself, is a figure of some repute, given that he’s leveraged his stature as Captain America’s best friend into an election as a U.S. Congressman. (His famous vibranium arm is revealed here to be dishwasher-safe.) But Bucky’s presence emblematizes what’s both cute and annoying about Thunderbolts: Its main cast comprises people who have previously appeared in the MCU, albeit as sidekicks, villains, or outcasts. We first met both Yelena (Florence Pugh) and her father, Alexei (David Harbour), in Black Widow, where they served as nuclear-family foils and allies to Scarlett Johansson’s now-dead avenger. One of the heavies in that movie was Taskmaster (Olga Kurylenko), who appears and disappears here so quickly, I didn’t even realize her involvement until the credits rolled. Speaking of vanishing: Do you remember Ava Starr, aka Ghost (Hannah John-Kamen), the troubled antagonist from Ant-Man & the Wasp who was blessed and cursed with the knack for becoming incorporeal, allowing her to walk through walls and maybe blink out of existence? If not, then you surely don’t recall John Walker (Wyatt Russell), the telegenic dude from The Falcon and the Winter Soldier who temporarily succeeded Steve Rogers as the next Captain America before a slight case of murder cost him the gig.

You can see my issue. The Marvel films have always felt a bit like homework assignments, rewarding viewers who study the intersecting pieces of franchise lore while flunking the uninitiated who wallow in a fog of confusion. To the extent Thunderbolts fancies itself a corrective to the MCU’s ongoing drudgery, its Frankenstein approach—mashing together disconnected characters whose gifts and flaws we’re expected to have already memorized—means it’s working at cross-purposes. And yet, such foreknowledge isn’t really essential to enjoying this latest entry, because Thunderbolts is less about perpetuating a continuing saga (it’s the final episode of Phase Five, whatever that means) than about exploring the collision of its strong-willed personalities. The movie’s gamble is that you don’t need to possess a doctorate in comic-book history in order to appreciate its feuding characters and its playful comedy.

It’s a smart bet. The best scenes in Thunderbolts (the official title includes an asterisk whose significance is revealed during the closing credits) have nothing to do with the Avengers, Dr. Doom, or (shh) the impending integration of the Fantastic Four. They instead involve the central characters—an assortment of goofballs and also-rans who have no visible credentials that would warrant them headlining their own blockbuster—simply squabbling, bonding, and collaborating. It’s not about the end of the world; it’s about how the world can feel like it’s ending when your parents embarrass you in front of your new friends. (Forgive the lack of context, but I’m still savoring Harbour’s deranged reading of the line, “Yelena! It’s your dad!!!”)

Not that the movie is devoid of plot. Its inciting incident is an impeachment inquiry brought against Valentina Allegra de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), the unscrupulous CIA director who’s been overseeing extralegal and experimental operations around the globe. (The most fantastical element of this comic-book picture is its vision of a Congress that might actually stand up to the executive branch’s abuses of power.) Insistent that national security demands biologically enhanced warriors, Valentina has conspired to create a new superhero called the Sentry, an invulnerable guardian with godlike powers. Yelena and her fellow misfits—the origin of their titular moniker is too adorable to spoil—represent both Valentina’s employees and her obstacles to implementing this stratagem.

Naturally, the narrative’s machinations require the Thunderbolts to frequently fight various foes and one another, generally in abandoned hangars, empty deserts, office towers, and other venues that can be easily replicated on a studio backlot. The mundanity of these locations is customary for the MCU, though the caliber of the action represents a marginal improvement on the series’ typical computer-generated light shows. Schreier, a TV journeyman and music-video director making his first feature in a decade, isn’t a great choreographer, but he doesn’t clutter the frame, which means all of the spear-hurling and shield-tossing is reasonably legible. (Yelena’s early rampage in Malaysia is captured in a graceful single take that recalls the classic hammer fight from Oldboy if shot from above, though the film doesn’t remotely aspire to Park Chan-wook levels of visual ambition.)

Besides, Thunderbolts isn’t really an action movie. It’s more of a workplace comedy, and its script flashes sufficient wit to prevent the dialogue from coming off as engineered banter. Pugh and Harbour already honed their daughter-father chemistry in Black Widow, and virtually every scene between Yelena and Alexei—she’s searching for deeper meaning, he just wants to be famous—is charming. There’s a cute bit where Yelena, Ava, and Walker—along with a new character, Bob (Lewis Pullman), whose apparent ordinariness masks a more disturbed and disturbing agenda—find themselves trapped in a vast vertical shaft, and the tactics they apply to escape are the opposite of conventional superhero maneuvers. Around the same time, Bob is shocked to discover that Walker briefly served as Captain America: “It’s just… you’re an asshole.”

Funny! And yet, in its third act, Thunderbolts actually becomes kind of scary, as our (anti)heroes battle one of society’s most fearsome enemies: depression. A lengthy sequence set in a shadowy realm, where Yelena and others must confront the demons of their past, exhibits a surprising level of storytelling bravery, eschewing the usual sound-and-fury nonsense in favor of more intimate doom and danger. This is also where the casting of Pugh pays off; she’s good throughout (the black leather combined with blue eyeliner doesn’t hurt), but her ability to imbue outlandish circumstances with brittle humanity allows the movie’s familiar themes of self-doubt and redemption to acquire genuine heft. There’s also a moving moment involving a very big rock where the once-divided gang demonstrates the power of unity; sure it’s hoary, but it works.

The smirking Deadpool pictures pride themselves on mocking the Marvel machine from within, but Thunderbolts is a more meaningful act of subversion, even if it can’t help but be at war with itself. As is standard with MCU fare, it features multiple post-credits scenes, and the final one dutifully primes viewers to anticipate future installments. But it’s the mid-credits stinger—which both honors Alexei’s courage and ridicules his vanity—that better encapsulates the movie’s impish-yet-wholesome spirit. Maybe the Thunderbolts can’t save the world. But with their verbal sparring and their grudging teamwork, they can at least rejuvenate a cinematic universe.

Grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.