NOMINEES

Frozen River – Courtney Hunt

Happy-Go-Lucky – Mike Leigh

In Bruges – Martin McDonagh

Milk – Dustin Lance Black

Wall-E – Andrew Stanton & Jim Reardon

WILL WIN

Ah, now here’s a category. Gene Siskel always used to say that the Best Original Screenplay nominees comprised the second-most important grouping of the Oscars after Best Picture, and while I rarely agreed with anything Siskel said or wrote, he was on the right path. Cinema, despite being a visual medium, is first and foremost about storytelling, and movies that receive their genesis from an original script represent the pinnacle of filmmaking creativity. This is not to say that an original screenplay is a prerequisite for a great movie – on the contrary, most of my favorite films are based on novels – but that the Best Original Screenplay category is important because it honors screenwriters who advance the boundaries of cinema. Ideally, the winner of the category will be entirely new – we’ll never have seen anything like it. (Hopefully that’s the case here, but we’ll get to that.)

It’s somewhat fitting, then, that the five screenplays nominated here exhibit tremendous variety. There’s a chilling look at poverty and what people will resort to in order to escape it (Frozen River), a character study of a woman of indefatigable pluck (Happy-Go Lucky), a comic thriller about two hit men vacationing in Belgium (In Bruges), a biopic of a revolutionary gay politician (Milk), and a near-silent love story about two robots (Wall-E). I’m not necessarily enamored with all of these movies, but I do applaud the Academy for selecting five screenplays that illustrate the wide breadth across which contemporary cinema currently stretches.

So who wins? It’s tempting to immediately pick Milk because it’s the lone Best Picture nominee of the group, but that might be a bit too easy. For all its supposed inclinations toward orthodoxy, the Academy has historically rewarded originality in this category (which, you know, makes sense given that it’s called Best Original Screenplay). Not only have quirky pictures such as Juno and Little Miss Sunshine walked away with Oscars for their screenplays, but three movies this decade have won the honor absent a Best Picture nomination (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Talk to Her, and Almost Famous). So Milk is far from a sure thing.

That said, I don’t see either Happy-Go-Lucky or Frozen River claiming gold. Mike Leigh has been nominated thrice before, but his scripts appear to be a bit too free-wheeling (and perhaps too British) to actually win the award, while Courtney Hunt’s tale of woe in Frozen River is so stark and depressing that it’s easy to admire but difficult to adore. As for In Bruges, the movie is just too damn eccentric (if jovially so) to take home a statuette.

The lone challenger, therefore, is Andrew Stanton’s and Jim Reardon’s screenplay for Wall-E, and it’s here where I have to hope that Academy voters try, to the best of their ability, not to be stupid. There is pessimism among Wall-E’s supporters that, because the movie contains very little actual dialogue, voters will perceive its script to be inconsequential, erroneously believing that dialogue is the sole criterion in evaluating a screenplay’s merit. (Guy Lodge took this philosophy to task over at In Contention – hopefully his readership among Oscar voters exceeds mine.) This is, of course, utterly moronic; a screenplay’s primary facet isn’t the quality of its dialogue but its story, and Wall-E is pure story, no matter how many spoken words it contains. But should the Academy neglect this obvious truth and instead adopt the Neanderthal mentality that a screenplay equals the sum of its words, Wall-E is in trouble.

But you know what? Let’s be optimistic. After all, the Academy was sensible enough to nominate Stanton’s and Reardon’s screenplay in the first place, so surely they can’t be as idiotic as I’ve just suggested. Besides, awarding Wall-E an Oscar for its screenplay can serve as voters’ collective (and feeble) apology for failing to nominate it for Best Picture. (What’s that? Wall-E was only excluded from Best Picture because of the existence of that infernal Best Animated Feature category? Nah …) Best Original Screenplay is an important category, and its winner should be an important film. Wall-E is it.

SHOULD WIN

Alright, I’ll just come out and confess: I haven’t seen Happy-Go-Lucky. I really do apologize. I always make a concerted effort to see every single movie that receives an Oscar nomination, and on balance I think I did a pretty solid job this year, given that Mike Leigh’s film is literally the only such feature I haven’t yet seen (excluding documentaries and foreign-language films). I was planning to see it at the Boston Common, which conveniently played the trailer for Happy-Go-Lucky multiple times; naturally, they refused to actually screen it. (Other movies the Common teased me with this year before ultimately failing to deliver include foreigners The Class and Waltz with Bashir, as well as Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York.) The DVD isn’t being released until March 10, and I just can’t will myself to download the movie online – not because I’m morally opposed to it but because I refuse to watch a feature film in crappy quality on a 17-inch screen.

(And yes, I probably could have seen the movie at Kendall Square in Cambridge, but I didn’t, and on that note, I have an announcement: I am done with Kendall. I know we’ve had our problems in the past, but I’ve always been willing to give it another shot. No longer – it is fucking over. The screens are small, the sound quality is poor, the prices are high, and the place is smack in the middle of motherfucking Cambridge – I’d rather drive to a theatre in Beirut. A month ago, I felt desperate to see Wendy and Lucy because Michelle Williams was receiving Best Actress buzz (whoops), only it wasn’t playing at the Common, so my friend Kerry and I went to see it at Kendall. What a disaster. It honestly took me 30 minutes to drive a quarter-mile once I got into Cambridge, and there wasn’t even any road construction. We actually both wound up making the movie on time, but only after I parked on the fourth floor of the garage and murdered a couple of senior citizens with Clemenza’s garrote from The Godfather in order to free up seats. At least the movie wasn’t horribly depressing or anything.)

So, anyway, yeah, I can’t comment on the quality of the screenplay of Happy-Go-Lucky. Sorry.

As for the remaining nominees, Frozen River is impressive in that it’s both compelling and fiercely unsentimental, but its minor characters are poorly developed, and some of the plot points of its final act are tough to swallow. The story of In Bruges is thoroughly entertaining, but I had a hard time taking it seriously, and it isn’t quite funny enough to succeed as a comedy. Milk, for its part, is a perfectly well-made film about an extraordinary individual, but Dustin Lance Black’s screenplay, while serviceable, fails to distinguish itself.

Having dispensed with the other candidates, my chosen winner is thus Wall-E, but don’t confuse this as mere process of elimination. Andrew Stanton’s and Jim Reardon’s story, about a robot assigned to dispose of trash and instead finding hope, is simply magnificent. The writers don’t need words to tell their story because it’s a story that transcends spoken language. Its themes of perseverance and undying love are universal, and they are expressed with such subtlety and humor that the film’s story is everlasting. Playful in tone but pure of heart, the screenplay of Wall-E is one for the ages.

DESERVING

Vicky Cristina Barcelona – Woody Allen. It’s a bit baffling that Woody Allen, who already had an astounding 14 Best Original Screenplay nominations under his belt, didn’t earn one for one his best scripts in years. Absent Allen’s usual hyper-neurotic pandering and self-effacing humor, Vicky Cristina Barcelona instead focuses on characters, creating several memorable and fully realized personalities. I’ll concede that the narrator is a bit of a crux, but the voiceover integration is at least handled gracefully, and for the most part Allen’s writing is fluid and intelligent without ever seeming pretentious. The Academy really missed one here.

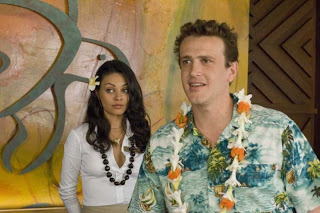

Forgetting Sarah Marshall – Jason Segel. Sure, there are a ton of funny lines, and sure, Aldous Snow immediately enters the Hall of Characters (“I was gonna listen to that, but then I just carried on living my life”), but the movie, for all its hilarity and hijinks, is actually, well, sort of real. I love the moment early on when Peter is explaining to his stepbrother that he’s deleting all the pictures of Sarah from his computer because he can’t be surrounded by her anymore, only his stepbrother realizes that Peter isn’t even deleting them properly, and Peter meekly confesses that he wants to keep the pictures backed up in case he and Sarah get back together. Look, you can’t quite appreciate that kind of stuff unless you’ve ever been miserably depressed over a girl, but that shit happens! That’s what’s great about Judd Apatow’s movies – they’re funny, yes, but they’re also based in truth.

(And just in case you think I’m being overly sentimental with this emotionally tinged shtick, let me emphasize that the writing is also really funny. Just take a look at some of the lyrics in “Peter You Suck”: “Go see a psychiatrist / I hate the psychiatrist! / Well go see one anyway!” Emotional depth or not, that shit is funny.)

Gran Torino – Nick Schenk. There’s a beautiful simplicity to Gran Torino, and while the delivery of some of the movie’s large-scale themes – racism! tolerance! redemption! – could have been heavy-handed, the film’s story is so organic that its theses emerge naturally rather than being obtusely conveyed. It helps that Schenk’s script is generous in humor as well as message.

The Bank Job – Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais. I can’t vouch for the accuracy of this film’s depiction of the infamous 1971 Baker Street robbery, but the screenplay seethes with verisimilitude. Dozens of nefarious characters are introduced, but Clements’ and La Frenais’ script properly identifies them and their associated role in the heist. It’s an impressive feat of storytelling, even if it helps that they were given an incredible true story to begin with.

Quantum of Solace – Paul Haggis, Neal Purvis, & Robert Wade. I know the editing was sloppy and the action scenes were borderline incoherent, but I really like what this screenwriting team – the same creative forces behind the adaptation for Casino Royale – is doing with James Bond as a character. More distant yet more human, 007 is no longer a suave, slick super-agent; he’s a troubled force of destruction seeking to find his identity in a world full of violence and evil. The scene in which he gets drunk on a late-night plane ride – not on shaken-not-stirred martinis, by the way – reveals emotional depths heretofore unheard of in Bond lore. It’s a cold new world out there, and James Bond is learning how to cope with it. The film’s stunningly tender final scene shows he may be on his way back.

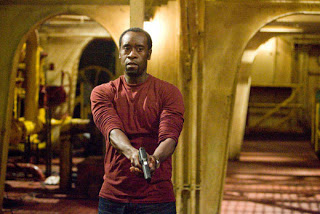

Traitor – Jeffrey Nachmanoff. It’s challenging enough to create a complex story set amidst the backdrop of modern-day terrorism. It’s more daunting still to fashion your protagonist not as a heroic white knight but a religiously fervent Muslim who just may be on the other side. Traitor may not have all the answers about the current global climate, but it at least asks a number of the right questions, which is more than most thrillers do these days. It is also distressing for its horrifically realistic depiction of how youth can become corrupted in the service of terror.

Rachel Getting Married – Jenny Lumet. Like father, like daughter. Sidney Lumet has earned five Oscar nominations over the course of his illustrious career (four as a director), and while Jenny is hardly in his class yet, her screenwriting debut shows unmistakable promise. Ostensibly the tale of a dysfunctional family, Rachel Getting Married supplies neither a host of caricatures nor a recipe for salvation. Instead it gives us glimpses into real people’s lives, as well as several scenes of raw emotional power. This will not be the last time you hear Jenny Lumet’s name.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.