Lists are idiotic. I love them.

But here’s the thing: Who doesn’t love reading lists? They’re easy and breezy, they inspire debate (perhaps in the Bizarro universe, one of my posts will set off a firestorm of controversy amidst my readership), and they’re an effective means of encapsulating all of my far-flung thoughts that inevitably accumulate over the period of a year.

Or in this case, a decade. As the first 10-year span of the new millennium comes to a close (well, technically the new millennium didn’t begin until 2001, but never mind), commentators from all corners of the blogosphere are compiling decade-long compendiums, and far be it from me to miss out on the fun. Sure, I’m being completely hypocritical, but hey, what my readers want, my readers get. (That none of my readers has made any such demand is a fact I choose to ignore.)

I’ll unveil my list of the best movies of the decade in the near future, but I figured I’d ease in with something a bit more modest (though only slightly). Therefore, what follows is the Manifesto’s list of the top 10 performances of the 2000s. I decided to restrict myself to lead performances, mainly because I wanted to focus on actors who clearly carried their movies. So, much as I adore the work of, say, Philip Seymour Hoffman in 25th Hour and Emma Watson in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, they’ll have to settle for my silent admiration for now. It also breaks my heart that I couldn’t find room for many of my favorite actors (Tom Cruise and Tobey Maguire, to name just two), but 10 is a cruelly small number.

So it goes. Speaking of truly heart-wrenching decisions, the following performances constitute my honorable mention – an eleven-way tie for eleventh place. In alphabetical order: Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Russell Crowe in A Beautiful Mind, Daniel Day-Lewis in Gangs of New York, Anne Hathaway in Rachel Getting Married, Bryce Dallas Howard in The Village, Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge!, Keira Knightley in Pride & Prejudice, Jared Leto in Requiem for a Dream, Campbell Scott in Roger Dodger, Denzel Washington in Training Day, and Kate Winslet in Little Children.

On to the decathletes. For those with an Oscar bent, only three of the following 10 performances received nominations from the Academy, with only one actor taking home a statuette (I’m feeling pessimistic and assuming that my one selection from 2009 will fail to garner a nomination). But as I’ve always said, fuck the Oscars. (Actually, I’ve never said that. I love the Oscars – they’re the reason this blog exists. No matter.) Here are the Manifesto’s top 10 acting performances of the 2000s:

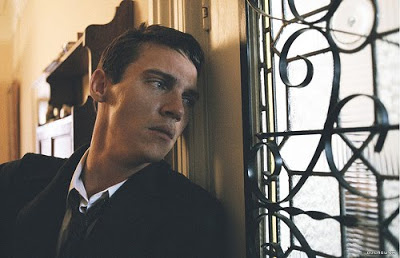

10. Jonathan Rhys Meyers – Match Point (2005). Acting is easier when the performer has something to do – a facial tic, an accent, a big speech, anything showy. As the exceedingly polite, disturbingly handsome tennis pro in Woody Allen’s Match Point, Rhys Meyers has no such luxuries. As a result, he’s forced to convey his character’s gradual descent into moral oblivion almost entirely through silence (thankfully, Allen refuses to give him a voiceover as a crux), and he does it beautifully. He speaks mostly with his eyes; watch the way they flit nervously around a room even as he’s coolly standing still, the way he sizes up a situation. The turning point in the movie is actually one of inaction, when Rhys Meyers decides – with exquisite hesitation – not to answer a phone call. It’s a marvelously controlled performance, and it gives us complete access to an individual who is, at least to all others around him, inaccessible.

9. Joseph Gordon-Levitt – Brick (2006). Most critics will point to 2005’s Mysterious Skin as Gordon-Levitt’s coming-out party, and they wouldn’t be wrong. But he takes things to a whole new level in Brick, simply disappearing into the potentially ludicrous role of a teenage Bogart scrambling to uncover the whereabouts of his ex-girlfriend. Brick essentially takes place in an alternate reality, where characters speak in the mannered beats of the noir dialect. (“Do you trust me now?” “Less than when I didn’t trust you before.”) It’s a bold, risky move from first-time director Rian Johnson, but Gordon-Levitt, who appears in every scene in the film, sells it completely. With hunched, introverted body language that seemingly contradicts his aggressive, rapid-fire style of speech, he’s completely convincing as a hardboiled super-sleuth. Listen to him talk tough to a gang of local heavies: “I got all five senses and I slept last night, that puts me six up on the lot of you.” Watching Gordon-Levitt, we aren’t looking at a scrawny high-schooler playing hooky; we’re watching a man possessed.

8. Jennifer Westfeldt – Kissing Jessica Stein (2002). The character of the neurotic New York Jew has been a bit of a cliché ever since Annie Hall, but there isn’t a hint of artifice in Westfeldt’s free-wheeling portrayal. An obsessive, hyperactive, totally gorgeous woman yearning for romance, her quest is doomed because she’s incapable of finding anything but fault in her potential partners (well, male partners anyway). The movie’s premise, involving a straight woman tentatively exploring a same-sex relationship, is one rife with laughs, but it could have come off as implausible were it not for the extraordinary nuance Westfeldt brings to her role. Her timidity regarding her decision is palpable, but it’s matched by her sheer desperation. “Sometimes I feel like I’m going to be alone forever,” she says in a devastating moment of emotional fragility, and that fear catalyzes her into action. By turns poignant and hilarious, brilliant and discombobulated, this New York Jew is in no way a stereotype.

7. John Cusack – High Fidelity (2000). Cusack has taken some deserved flak throughout his career for essentially essaying over and over again the character that first made him famous. That would of course be Lloyd Dobbler in Say Anything, a youth so gentle and heartwarming that it’s hard to blame Cusack for going back to the well a few times. But his incarnation of Rob Gordon in High Fidelity is another beast entirely. Bitter, broken, and seething with self-righteous anger, Rob is just as compelling as Lloyd but nowhere near as perfect. But his imperfections are what make him interesting, and Cusack shrewdly emphasizes Rob’s pathetic tendencies along with his sharp intelligence and quick wit. One of the greatest talk-to-the-camera performances ever, it is also one of absolute honesty. Watch Cusack’s face when he tells us that he cheated on his girlfriend, the way the shame mingles with the resentment. There’s real emotion there, but Cusack isn’t begging for our sympathy – he’s just reminiscing about his ex, the way we all do. That frankness, along with some effortlessly natural (and very funny) humor, makes Rob fascinating. At one point, Rob wonders openly why someone as average as himself has “become the number one lover-man in his particular postal district”. The answer lies in Cusack’s performance; he may not be a great guy, but he’s great fun to be around.

6. Jenna Jameson – Dreamquest (2000). Just kidding. Although you could make the argument that … never mind.

6. Tilda Swinton – Julia (2009). If you’ve never heard of this movie, you aren’t alone – it made just $64,000 at the box office before disappearing from U.S. screens forever. And that’s a terrible shame, because Swinton’s performance as a supremely reckless alcoholic is absolutely riveting. There’s a wonderful sense of improvisation about her acting, as though she’s inventing the character as she goes along. Yet as is the case with many great British actors (she’s playing American here, just to up the ante), her work is also fastidiously controlled, full of subtle beats and precise movements. There’s a terrific moment halfway through the film when Swinton’s title character realizes that she’s made a crucial mistake, and recognition splashes across her face like a glass of ice-water. But seconds later, after a seemingly physical effort to regain control, her face again assumes a mask of indifferent passivity – the ice-queen reclaiming her throne. I might never see Julia again (its release on Blu-ray seems ill-fated at this point), but Swinton’s performance has forever seared itself into my memory.

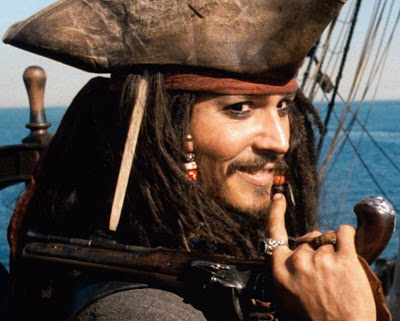

5. Johnny Depp – Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003). There are unconventional action heroes, and then there’s Captain Jack Sparrow. Armed with a rapier wit to go with his actual rapier, he’d rather swashbuckle his way out of danger than gallantly save the day. “Will you be saving her, then?” he asks a pair of bumbling sailors as a damsel plunges to her distress, before reluctantly doing the deed himself. But buried beneath the drunken lurches and spouts of verbiage (“nigh uncatchable!”), there’s a quiet sense of nobility to Captain Jack. He may be a no-good bloody pirate, but at least he believes in something. That lends a certain dignity to a performance that is otherwise gleefully undignified. Simultaneously the smartest man on the ship and the looniest, Captain Jack is a spectacular condemnation of the classical action hero, and with his limp-wristed movements and sardonic delivery, Depp invents an entirely new archetype. In an era in which studios are routinely criticized for distributing derivative entertainment, we can feel confident knowing we’ve never seen anything like Captain Jack.

4. Daniel Day-Lewis – There Will Be Blood (2007). There’s a great moment in “The Office” where Steve Carell says, “It takes a big man to admit his mistakes. And I am that big man”. Well, I am also that big man, because two years ago, while discussing There Will Be Blood, I suggested that Day-Lewis’ crowning achievement was his work as Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York. I maintain that his earlier effort is a seminal piece of screen acting (it did make my honorable mention, after all), but after viewing Paul Thomas Anderson’s epic a second time, I’m forced to concede that Day-Lewis’ work as Daniel Plainview is the superior performance. Whereas the Butcher is openly toxic and hateful, Plainview conceals his disgust of people with a veneer of politeness. He despises humanity – at one point, he confesses as much to a confidant (whom he soon kills, but no matter) – but the political nature of his occupation (“When I say I am an oil man, you will agree”) requires that he treat lesser beings with courtesy and respect. Yet every so often his rage boils over, and the monster who emerges is truly terrible to behold. Plainview is cordial, efficient, and ruthless; he is also lustful, vengeful, and beyond redemption. Day-Lewis somehow makes him all these things and does so cohesively, so that Plainview’s disparate qualities are but many warring parts of a single, rotted soul.

3. Leonardo DiCaprio – The Departed (2006). Was this the Decade of DiCaprio? Perhaps if Shutter Island (get psyched) and Inception (get very psyched) had come out a year earlier, but even so, the man has been on a historic run the past seven years, ever since his breakout performance in Catch Me If You Can. But his role as Billy Costigan in The Departed is his true masterwork, an enthralling portrayal of violence, charisma, and fear. As an undercover cop nestling his way into the inner circle of the mob, Billy is both smart and capable. He’s also scared shitless, not just of being discovered but of losing himself in the darkness he’s been charged to bring down. DiCaprio plays Billy as a wounded animal, frenzied and frightened but also lethal when cornered. He also exudes a furious intensity – one always gets the sense he’s a hair’s breadth away from exploding into violence – yet he combines that ferocity with genuine vulnerability and confusion. It’s a magnetic performance from a singularly talented actor at the peak of his art form.

2. Keira Knightley – Atonement (2007). This should really be #1, but I decided that she didn’t possess quite enough screen time to earn the top slot on my list. But her penultimate ranking does nothing to diminish this unassailable fact: This is the most emotionally devastating performance I have ever seen. I discussed it in extensive detail here, so I won’t get carried away a second time. Suffice it to say that acting is all about feeling – the great actors make us feel what they’re feeling, be it through body language, intonation, eye movements, anything. And everything Keira Knightley does in her portrayal of Cecilia Tallis makes me feel exactly what she’s feeling. Pain, passion, hesitancy, desperation, fury, longing, hope, and most of all despair – it’s all there. I often half-jokingly (emphasis on “half”) complain about how actresses refuse to show their bodies on camera, but in Atonement, Keira Knightley does something far more challenging and rewarding: She shows us her soul.

1. George Clooney – Michael Clayton (2007). Strangely, this could probably double as the “most underrated” performance of the decade. Audiences seemed to forget about Clooney, perhaps because he found himself competing against the behemoth that was Daniel Day-Lewis in the 2007 Oscar race. More likely it’s that viewers prescribed to the gross misconception that he was merely playing himself. Wrong. So very wrong. Clooney is an undeniably hypnotic presence, both on-screen and off; perhaps the most charismatic figure in Hollywood, he simply oozes cool and self-confidence, and that’s often the case in many of his film roles (see the Ocean’s movies). But not in Michael Clayton. Here, he’s a broken man, financially scrambling, spiritually crumbling. Sure, Michael works as a fixer at a powerhouse law firm, but what does he really have? No job security, no close friends, no marriage, no direction – he’s a man without a country. I wrote about the performance at length here, so let me simply recall the scene in which Clooney meets the morning sunrise alone. It’s a stunning moment of nonverbal acting – technically brilliant but also incredibly potent – and it reminds us what movie stars can do. They can show us people not unlike ourselves, bring us into their lives, and in doing so, just maybe enrich our own.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

Just watched Up In the Air- it was pretty great- shouldnt Clooney get props for that (though i like him as #1 for Michael Clayton)? Also, I am disappointed that you only gave Jim Carey an honorable mention for Eternal Sunshine- he was amazing, as was the movie as a whole. Despite this, I am happy you recognized Joseph Gordon-Levitt- i love him.

I know you loveee Keira Knightley, but i also expected Kate Winslet to be on there for Rev. Road or The Reader (ps: because Tilda doesnt actually qualify as a women, this was a totally male dominated list).

Finally- what about Guy Pearce in Momento (2000)? Sean Penn in Milk (2008)?

Love the post!

I thought Clooney was great in Up in the Air — he might wind up with my vote for Best Actor in 2009 — but he's more in his comfort zone there. In Michael Clayton, he's on a different plane.

Carrey was a tough decision, and he very nearly made the final cut. It's still easily the performance of his career, and that's saying more than most people realize.

Were it not for DiCaprio, Winslet might have been the actor of the decade. She's just an automatic home run at this point. I went with Little Children on honorable mention partly because it's less showy than her spell-binding work in The Reader, and partly because she didn't have the luxury of a killer co-star (as she did in Revolutionary Road and Eternal Sunshine), but it's hard to argue with any of her performances.

Regarding your utterly baseless (and sarcastic, I know) accusation of chauvinism, if we assume that Tilda Swinton is in fact a woman, then I could have done a lot worse than a 70-30 split. Throw in the fact that five of the 11 honorable mentions were ladies, and I'm not losing any sleep. I am marginally ashamed that I failed to include an actor from a foreign-language film, but I see so few that some ethnocentrism is inevitable.

I love Guy Pearce and thought he was terrific in Memento, but I remember that movie more for the once-in-a-lifetime screenplay than for any of its actors. And I admired Sean Penn in Milk, but the performance, much like the movie, didn't really stick with me. I preferred him in Mystic River.

Thanks for the comments!