When we were growing up, my sister refused to watch foreign movies. I can’t recall her precise rationale for this, although given how childish we both were at the time, I’m not sure our reasoning processes could have been deemed to have anything resembling a “rationale”. I think she complained about having to read the subtitles, which didn’t make much sense given that she was perfectly literate. Regardless, whenever my father suggested watching a foreign movie, he was met with extreme disdain, not to mention occasional wailing.

Nowadays, armed with the power of a Netflix account, my sister probably watches 5-6 foreign movies each month. This victory over her earlier cinematic xenophobia can largely be attributed simply to growing up, but I’ll tentatively argue that it’s symptomatic of our country’s maturation toward foreign movies as a whole. Over the past decade, films like Amelie, City of God, and Pan’s Labyrinth have gained prominence not just abroad but within American cultural circles (all three earned major nominations at the Oscars, not just for Best Foreign Language Film). As a national collective, our moviegoing tastes have ever-so-gradually expanded, and subtitled pictures lack the stigma they once possessed.

Of course, there’s still work to do. Distribution for foreign films, though improving, remains woefully inadequate, meaning that most American moviegoers have to wait until the DVD release in order to partake in imported entertainment. Fortunately, the advent of Netflix is a tremendous boon to viewers who desire to expand their horizons beyond our borders. As consumers, we are no longer at the mercy of the tyrannical multiplex infrastructure; if we want to watch a movie about suicidal Turkish lovers, you’re not going to fucking stop us.

Don’t misunderstand me: I’m in no way decrying the current state of American cinema. I’ve always fashioned myself a champion of mainstream movie entertainment, and there’s a great deal to like about a number of studio-helmed blockbusters that dominate the contemporary landscape. There’s just no reason to limit our collective sphere of interest when we can finally gain access to the fertile soil that’s available overseas.

To that end, this post is designed to introduce readers to 20 high-quality foreign films of which, for whatever reason, you just aren’t aware. (Note that by “foreign” I really mean foreign language, so movies from Britain and Australia are ineligible. Also note that all but two of my selections are from this past decade because, well, such is life.) Now, this compendium is by no means intended to be an all-encompassing. Obviously there are hundreds of other excellent foreign films out there that I’ve excluded, either because I’ve forgotten about them or – more likely – I simply haven’t seen them. That’s the great thing about movies: There are always more good ones to watch.

So, feel free to sound off regarding any particularly egregious omissions in the Comments. In the meantime, if you’re feeling avant garde or just in the mood for some foreign flavor, you can’t go wrong with any of these. In no particular order (i.e., I spent three hours carefully selecting the order, but I can’t possibly describe the method to my madness) …

4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days (Romania, 2007). This one’s a no-brainer. Cristian Mungiu’s ferociously gripping drama set during the Romanian dictatorship in 1987 starts off slowly, as we meet two friendly female college students who seem to be planning some sort of trip. By the time it ends, Mungiu has subjected both his characters and his audience to primal fear and grotesque villainy, all presented with prosaic, chillingly observant technique. Featuring a number of excruciatingly long handheld takes, Mungiu’s camera makes no comment on the bleakness of his characters’ predicament, though the body language of his actors – most notably the achingly sympathetic Anamaria Marinca and the quietly terrifying Vlad Ivanov – says plenty. Stylistically austere, 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days uses no music whatsoever, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t sing.

Just Another Love Story (Denmark, 2009). Love that title. Ole Bornedal’s chaotic, unpredictable thriller indeed focuses on just another everyman, a world-weary crime scene photographer played with perpetually expanding disbelief by Anders W. Berthelsen. One minute he’s on a routine investigation, and then suddenly he’s sleeping with an amnesiac in her hospital bed, ducking stares from an eerie masked man in a wheelchair (or did he imagine that?), and impersonating a shadowy figure who was murdered in the Thai underworld (wasn’t he?). Bornedal’s script zigs and zags frantically, resulting in a breathless, giddily entertaining thriller that gleefully toys with its viewers’ preconceptions. An American remake is already in the works, with (500) Days of Summer director Marc Webb rumored to be at the helm, and while a retooled script could provide some welcome ballast to Bornedal’s freewheeling twists and turns, it’s hard to imagine another love story quite like this one.

Let the Right One In (Sweden, 2008). Great, another fucking vampire movie. Hold on: The vampire in question is a skittish 12-year-old girl, and the movie is really about her gentle, burgeoning friendship with the bullied boy next door. Tomas Alfredson’s film is part tender romance, part delicate coming-of-age story, and part Carrie-esque horror. That might sound like an ungainly mixture, but Alfredson pulls it off thanks to true regard for his characters, as well as masterful command of his craft. There are moments in Let the Right One In – such as a scene in which the camera observes from afar as a figure silently scales a building – that constitute pure filmmaking on the level of Spielberg or, well, Brian de Palma. Cloverfield director Matt Reeves has a remake (titled Let Me In and starring Kick-Ass‘ Chloe Grace Moretz and The Road‘s Kodi Smit-McPhee) arriving in October, and while it may be a noble attempt to introduce American audiences to the mythology, it’s difficult to conceive how he can possibly improve on the original.

Pan’s Labyrinth (Mexico, 2006). If the goal of this list is to introduce readers to films they’ve never heard of, then Pan’s Labyrinth doesn’t really belong. It made a healthy $38 million at the U.S. box office and garnered six Oscar nominations (winning three); clearly, it’s already found its audience. But I just can’t leave it off. A supremely original story combining whimsical childhood fantasy and acutely adult rebellion against fascist rule, Guillermo del Toro’s majestic movie retains its innovative hue four years after its release. Originality may be a theme of this post as a whole, but innovation isn’t an end in itself – there are plenty of bad movies that are no less terrible simply because they’re original. But del Toro weaves his disparate threads together so fluidly that he creates a cohesive tapestry depicting both a child’s plight and a nation’s defiance. It’s a story that’s magical in any language.

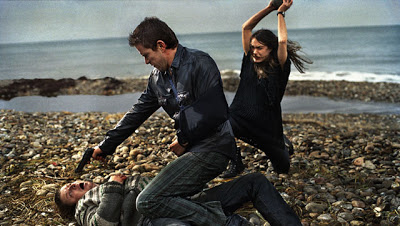

Tell No One (France, 2008). Pure suspense. Guillaume Canet’s thriller sinks its hooks into its viewers with a spooky, economical opening – a man gets knocked out, a woman disappears – and never relinquishes its hold. The screenplay, which spans at least eight years and half-a-dozen double-crosses, is frenziedly complicated in the vein of classic noirs like The Big Sleep, but Canet shepherds us along gracefully. He’s ably assisted by François Cluzet, who grounds the movie in his fiercely pragmatic performance as a doctor desperately trying to unravel the mystery of his wife’s death. The film’s high point is a frantic foot-chase across a highway, a sequence that is free of visible special effects but nevertheless matches the freeway chase from The Matrix Reloaded for verve and adrenalin.

Head-On (Germany, 2005). And here are those suicidal Turkish lovers I was talking about. Titanic twin performances from Birol Ünel and Sibel Kekilli drive Fatih Akin’s poignant drama about two desperate souls who find a measure of peace in each other. The photography is drenched in grime and grit – this is not a flattering portrait of Germany – and the narrative pulls no punches in its descent into despair (a stabbing sequence is particularly disturbing, as are multiple suicide attempts). Yet Head-On is somehow strangely optimistic, and it plays some light grace notes of humor and hope amidst its agony. There’s a lot of filth in the world, and this movie shows us plenty of it, but it also shows us how the intimacy of love can repel even the foulest elements of human nature.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Sweden, 2010). A self-described international sensation, the first installment of Stieg Larsson’s fantastically popular Millennium Trilogy surprisingly doesn’t cater to typical populist tastes. It is pervasively, almost uncomfortably violent, and it traffics in seedy topics such as incest, rape, and Nazism. It is also riveting entertainment. Briskly paced and tightly plotted, it shades its lead characters with depth and nuance incongruous with its pulpy subject matter. And the performance of Noomi Rapace is revelatory. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo represents yet another film on this list rumored to be the target of an American remake, this time with David Fincher behind the camera and, um, Carey Mulligan in the title role. Don’t get me wrong, I think Carey Mulligan is an excellent actress, but I can’t possibly see her matching Rapace’s intensely focused ferocity. Best not to try.

The Wages of Fear (France, 1953). Whoa, wait a minute – 1953? Sue me, I watched it for the first time a few years ago. And unlike a handful of films deemed to be critical classics (cough, The Rules of the Game), I was fully on board with this mesmerizing thriller. After a meandering first half that wanders aimlessly through a dilapidated village, Henri-Georges Clouzot abruptly centers his film on a simple task: Four men must navigate two trucks laden with explosives across twisting roads and treacherous terrain. The setup is simple, but the execution is magnificent. As Clouzot’s relatively mundane heroes grapple with naturalistic elements such as a hairpin turn and a rickety bridge, he presents their challenges with uncanny detail. The term white-knuckle suspense is often misapplied, but it’s valid here – watching the trials in The Wages of Fear, you’ll be clenching your fists so tightly that you may as well be gripping that steering wheel yourself.

Waltz with Bashir (Israel, 2008). An animated documentary in Hebrew about a massacre in Lebanon? Who wouldn’t want to watch that? Documentaries, of course, are not my strong suit as a filmgoer – in fact, I basically can’t watch them – but the rippling animation in Ari Folman’s picture breathes life into its story of death. The movie is more a collage of memories than an admonition of military tactics, but it’s presented with such exquisite clarity that it generates a far more powerful experience than would have a mere collection of talking-head interviews. Waltz with Bashir may not hew closely to traditional narrative methods of documentation, but Folman’s creativity within the medium lends undeniable force to his message.

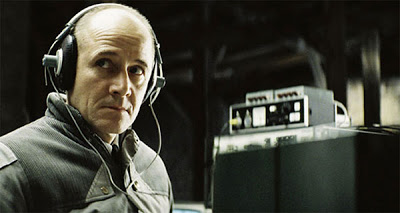

The Lives of Others (Germany, 2007). This Cold War thriller set in 1984 East Germany feels like it was made during the Cold War. Ostensibly the story of a popular novelist tentatively exploring the prospect of defection, the film really focuses on a secret police agent, played with heartbreaking loneliness by Ulrich Mühe. As the two characters slowly encroach on each other’s orbits, director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck (now there’s a name) heightens the tension, and we get a true sense of the claustrophobia and terror that pervaded the country and its citizens (not unlike the atmosphere of 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days). The film’s conclusion is both stirring and sad, a testament to the decency of humanity in its never-ending battle against the corrupt and the cruel.

He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not (France, 2003). If I had to pick a single film on this list that I’m confident you’ve absolutely never heard of, this is the one. Despite the presence of the singularly charming Audrey Tautou, Laetitia Colombani’s coy drama never crossed over. That’s unfortunate, because it’s the product of a daring, fiendishly clever screenplay that examines weighty romantic conceits such as destiny and true love but does so in a lithe, nimble style befitting its gamine star. The movie, like Tautou’s protagonist, at first appears to be fluffy and inconsequential, but as its narrative dips and dives, you realize it’s far more substantive that you thought.

Lorna’s Silence (Belgium, 2009). I don’t know much about the Dardenne Brothers, except that they’re allegedly masters of realism, or some high-brow crap like that. Ordinarily I shy away from cinema verite – mainly because I find it really freaking boring – but Lorna’s Silence is hypnotic in that way it captures the lives of its characters with pristine, clinical detachment. As the two leads, Arta Dobroshi and Jérémie Renier (the latter can be seen in remarkably different form in the critically acclaimed Summer Hours) are devastatingly real, and while the film’s conclusion is a bit too metaphysical for my tastes, there’s no denying the overall power of this tale of sacrifice, regret, and redemption.

House of Flying Daggers (China, 2004). The major knock on contemporary action filmmaking is that it’s too frenetic. Bullets whiz, cars fly, planes explode, editors cut, and the entire time the audience really has no clue what’s actually happening on screen. Zhang Yimou eschews this path in favor of a more elegant style, one in which both his combatants and his camera move with grace and fluidity. That makes the action in Zhang’s movie sound boring, but it’s anything but, as he choreographs his set pieces with the flair and artistry of a maestro – it’s just that he communicates the action to his viewers rather than assaulting us with sound and fury. Of course, action is subservient to story, and the story in House of Flying Daggers is appropriately solemn and earnest, while the performances from Takeshi Kaneshiro and Zhang Ziyi give the central romance the requisite weight. But it’s the elegance of Zhang’s filmmaking that makes the movie truly memorable.

Z (Algeria, 1969). I’m not much for politics in general, and that disdain often extends to my taste in film, but there’s something courageous about a movie that ends with the disclaimer, “Any resemblance to real events, to persons living or dead, is not accidental. It is DELIBERATE.” Yet one doesn’t need to be familiar with the political history surrounding Z‘s genesis in order to appreciate Costa-Gavras’ depiction of a ruthlessly corrupt government. Jean-Louis Trintignant – who appeared 35 years later in Kieslowski’s magnificent Red – is flawless as a lone honest bureaucrat attempting to expose the truth behind an assassination, but honesty and integrity are no match for the power wielded by the corrupt. Z may have been deliberately focused on a specific historical event, but its themes of governmental deception and tyranny remain resonant.

The Secret in Their Eyes (Argentina, 2010). The Oscar winner last year for Best Foreign Language Film, here is a movie that at first appears to be a standard police procedural only to transform into something else entirely. Of course, those procedural elements are pretty damn compelling, thanks to a tightly scripted screenplay and a heartfelt performance from Ricardo Darín; the film’s romance, while a tad malnourished, is similarly stirring. But it’s the finale of The Secret in Their Eyes that really packs a wallop, a mournful commentary on the fleeting nature of love and the corrosive power of obsession. The movie provides a hesitantly hopeful coda, and perhaps its characters have earned it after journeying through such despair for so long. But the darkness of that finale that haunts their eyes – and their lives – cannot soon be forgotten.

Thirst (South Korea, 2009). Park Chan-wook is best known for Oldboy, that rather revolting tale of a man kidnapped for 15 years who attempts to unleash vengeance on his captors. I found Oldboy to be intriguing but ultimately vile, but I responded quite differently to Thirst, the bizarre story of a priest who becomes a vampire. The absurdist tone of Oldboy is still present, but the characters in Thirst are far more sympathetic and interesting. The resulting confection is undeniably grotesque – this is a film about murderous vampires, after all – but there’s an odd sense of sentiment about the whole enterprise that lends it a curious appeal. Sure there is Park’s usual combination of gruesome violence and pitch-black humor, but Thirst has something else that elevates it above the canon of pulp: The movie – if not its characters – has a beating heart.

Infernal Affairs (Hong Kong, 2002). I’ve highlighted a number of films on this list that have been slated for Hollywood remakes in the future. Well, if you’re looking for someone – or something – to blame, look no further than this tidy little tale of police corruption and mob brutality. In 2006, a little-known filmmaker named Martin Scorsese refashioned this actioner into a little movie called The Departed. I won’t suggest that Infernal Affairs is the superior picture (though its ending is far, far superior to Scorsese’s), but it holds up just fine, untangling its twin stories of duplicity and betrayal with both energy and precision. The film lacks the sprawling ambition of The Departed, but it matches Scorsese’s version in terms of intensity and suspense, while Andy Lau and Tony Leung bring pathos to potentially stock roles. Though it spawned two messily enjoyable sequels, Infernal Affairs is best viewed on its own – when you do, you’ll find it doesn’t need to be compared against anything.

Sin Nombre (Mexico, 2009). There’s something highly pleasurable about sitting down to watch a movie and realizing you have absolutely no idea where it’s going. At first Sin Nombre appears to be a brutally frank look at gangland culture in Mexico, and in a way it is. But it’s also an out-of-nowhere character study and a thoughtful meditation on the instant decisions we make and their ultimate consequences. Cary Fukunaga could have made a pointed melodrama laced in despair, but he focuses instead on quiet character beats and unspoken moments. For a film rife with violence and conflict, it’s these beats of silence that speak the most.

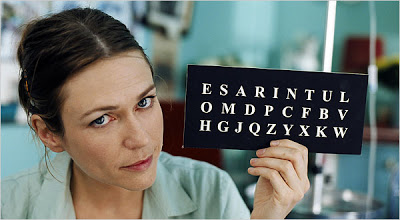

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (France, 2007). This one doesn’t really need my help either, as it earned four major Oscar nominations (though not one for Best Foreign Language Film, thanks to the Academy’s inane rules), but it’s worth seeking out regardless. The premise – a man who is completely paralyzed, except for his ability to blink one eye, develops a method of communication and ultimately writes a book – would be preposterous if it didn’t also happen to be true. Director Julian Schnabel improbably finds beauty in his protagonist’s predicament, and he exploits it through remarkably vivid photography (cinematographer Janusz Kaminski is Spielberg’s longtime collaborator) and keen ingenuity (the sequence where a needle dances toward the camera in its effort to sew an eye shut remains firmly etched in my memory). It’s a stranger-than-fiction type of tale, but after watching Schnabel wield his technique, it’s clear that a simple documentary would have failed to do this extraordinary story justice.

Curse of the Golden Flower (China, 2006). The second Zhang Yimou picture on this list, this one replaces the delicate subtlety of House of Flying Daggers with out-and-out decadence. This is not to suggest that Zhang has discarded his painterly gifts for nuance and detail, just that he’s employing those gifts on an exponentially larger canvas. Curse of the Golden Flower is a vaguely ridiculous epic, but it’s ridiculous in all the right ways and befitting its gargantuan scope. The action scenes have never been more elaborate, the colors never brighter, the production design never grander. Most filmmakers would crumble under a movie of such magnitude, but Zhang – who orchestrated the opening ceremonies of the Beijing Olympics – has never shown a surer hand. His actors join him in accepting the challenge. Chow Yun-Fat is mercilessly exacting as a cruel despot, but it’s Zhang’s perpetual muse Gong Li who infuses his squalid opera with a true sense of tragedy. The demise of a dynasty has never looked this good.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.