The Visit, a chintzy tale of low-budget horror, is the best movie M. Night Shyamalan has made in over a decade. This, of course, is hardly extravagant praise. But while Shyamalan, the cinematic-wunderkind-turned-critical-punching-bag, has helmed his share of recent misfires, those failings suffered less from a lack of artistic talent than a poor sense of scale. Certainly, his recent output—Lady in the Water, The Happening, After Earth—could charitably be deemed “not good”, but all three of those films had their minor virtues, particularly their director’s gift for nifty camerawork and provocative imagery. (Even the misbegotten Last Airbender had one good scene.) The problem was that Shyamalan didn’t want these movies to be good; he wanted them to be great, to be revolutionary, to capture the zeitgeist. Sadly, his clumsy storytelling dashed those hopes, and when you added his ham-fisted dialogue into the mix, the laughable writing masked the visual artistry. Shyamalan’s recent films didn’t fall short of greatness so much as they fell off a cliff.

The Visit is not a great movie (not even close), but the key to its relative success is that it doesn’t want to be great. This is a slender, modestly mounted fright flick—sometimes scary, sometimes funny, frequently ridiculous—and its lack of ambition frees it from the shackles of grandiosity. That in turn gives Shyamalan greater freedom to flex his filmmaking muscle, which he does with aplomb, repeatedly delivering memorable set pieces and exquisite framing. He’s always been good at that stuff, but here he hasn’t weighed himself down with a ponderous storyline, making this the first time he’s ever seemed relaxed.

The plot of The Visit, like its title, is refreshingly simple. Loretta (Kathryn Hahn, turning a smattering of moments into a character) fled home when she was 19 after becoming embroiled in an affair with her teacher, and she hasn’t spoken to her parents since. Now, 15 years later, her two plucky children have decided that she needs some alone time with her new beau in the form of a weeklong cruise. In the meantime, those children—15-year-old Becca (Olivia DeJonge, quite good) and 13-year-old Tyler (Ed Oxenbould, likably irritating)—will head to rural Philadelphia to meet their grandparents for the first time. What could go wrong?

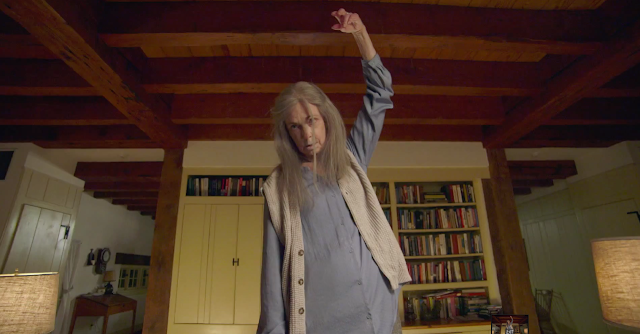

At first, not much. The grandparents, known only as Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Boardwalk Empire‘s Peter McRobbie), seem like perfectly charming old folks. Nana bakes slightly burnt walnuts, and Pop Pop shuffles about a bit aimlessly, but nothing about these coots seems all that crazy. They even cheer when Tyler, a wannabe hip-hop artist, performs an absurd impromptu rap about pineapple-upside-down cake. It’s family bonding! So when Pop Pop gently informs his grandchildren that bedtime is at 9:30 sharp, and that they should stay out of the basement because of the mold, it scans to the kids as little more than grizzled paternal warmth.

You know better, of course. It doesn’t take long before Nana and Pop Pop’s actions become increasingly difficult to explain. Nana is a bit of a klutz in the kitchen, and whoops, she accidentally just poured batter on the lens of Becca’s webcam. Pop Pop is often seen staring into the distance or ambling into the shed for extended periods of time, and wait, is that a shotgun? In stock horror-movie tradition, Shyamalan lets these trivial incidents gradually accumulate, slowly building tension while also supplying the occasional jolt-scare.

This is nicely done, but it’s nothing new. Virtually every modern horror movie starts out cooking at an enjoyable simmer before fizzling into an overheated climax (there are exceptions), and in this regard, The Visit is no different. What’s interesting here is Shyamalan’s choice of form. The Visit, you see, is the latest entrant in the irksome subgenre of found footage, that ill-advised fad that exploded with low-budget smashes like Paranormal Activity before swiftly wearing out its welcome. Thus, Becca is more than another sympathetic teenage victim; she’s an aspiring documentarian, and she’s resolved to film every moment of her and Tyler’s trip to their grandparents’ cozy cottage. And so, the entirety of The Visit purports to be actual footage captured by the kids’ twin handheld cameras.

This is by no means an original idea—it might be hard to believe, but there have already been five different Paranormal Activity movies, with a sixth due out next month—but it is a surprising one, given Shyamalan’s pedigree. His greatest asset as a filmmaker is his ability to manipulate the frame; say what you want about the plot of The Village, but Bryce Dallas Howard’s final journey into the woods remains a masterful display of how to use expertly cropped close-ups to induce maximum fear. But where Shyamalan’s technique has always been about discipline—recall the ingeniously distorted angles in the opening scene of Unbreakable—found footage is necessarily anarchic, with wavering handheld camerawork and explicit sloppiness. It would seem to be an ill fit for such a visually fastidious director.

Quite the opposite. The format gives The Visit some serious kick, as Shyamalan brilliantly toys with viewers in a variety of ways, both chaotic and controlled. An early hide-and-seek sequence, in which Becca and Tyler scramble under a catacomb-like maze beneath their grandparents’ house (all while steadfastly holding onto their cameras—even by horror standards, found footage requires significant suspension of disbelief), features just the right touch of confusion about a possible intruder, an uncertainty that elevates the suspense. Yet Shyamalan is even more effective when the kids put their cameras down, cannily using stillness and depth of field—in many instances, a threatening figure appears in the background, unbeknownst to the teenager in the foreground—to deliver organic scares.

As with most horror films, there is a certain level of sadism that underlies these proceedings; we are taking pleasure in observing Becca and Tyler’s pain. The Visit makes this dichotomy palatable, largely because its two heroes are stupid enough to deserve it. Becca and Tyler are sweet enough—DeJonge and Oxenbould demonstrate a genuine and unforced sibling rapport—but they probably aren’t making the honor roll. Sure, Hansel and Gretel made their share of dubious decisions, but they were at least smart enough to leave a trail of breadcrumbs. These kids actually think it’s a good idea to investigate the basement.

But The Visit isn’t about its characters being smart, which is why its third-act twist (a Shyamalan staple; come on, did you not see The Sixth Sense?) feels less cheap than harmless. It’s about its director recalibrating his ambitions to match his skills. There’s a goofy subplot in The Visit in which Becca is terrified of seeing her own reflection. It’s more than a little ludicrous, but it leads to a payoff that’s oddly satisfying. That satisfaction may stem from our recognition that, as this fun and foolish movie reveals, Becca isn’t the only one who’s finally learned to look in the mirror.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.