In 1972 in Iceland, Bobby Fischer attempted to become the first American-born man to win the World Chess Championship, seeking to wrest the crown from imposing Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky. Now, if you think that sounds challenging, try making a movie about it. Sure, sports films are only tangentially about the sports themselves, but they almost always revolve around some degree of dynamism or athleticism, some sort of physical heroism for the camera to capture. But Pawn Sacrifice, Edward Zwick’s dramatization of Fischer’s famous battle against Spassky and the Iron Curtain, is about chess, which is basically the least cinematic sport imaginable. Zwick’s seemingly impossible task is to transform a thoroughly sedate affair—one in which two men stare at carefully sculpted figurines, furrow their brows, and think—into an actual thriller of tangible urgency and excitement. He mostly succeeds. Functional, beautifully acted, and curiously engrossing, Pawn Sacrifice resembles the best traditional sports movie Zwick possibly could have made on this subject. In other words, it isn’t half-bad.

The film opens in medias res, after Fischer has forfeited the second game of the Championship (the rules provided for up to 24 total games) and has barricaded himself in his rented cottage, flinching at the slightest sound. It then flashes back to his childhood in New York, a predictable device that immediately illustrates both the benefits and the drawbacks of Zwick’s orthodox approach. The flashback, which is mercifully brief, does its job: It bluntly illustrates that Fischer (played as a young boy by Aiden Lovekamp and then as a teen by Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick) is both a genius and a prick. Expressing the former element proves problematic for Zwick; unable to telegraph Fischer’s virtuosity visually, he settles for dialogue, with adults repeatedly gushing about the boy’s brilliance, followed by a montage of handshakes soundtracked to laudatory notices from newscasters. (To be fair, Zwick initially toys with using graphics to convey Fischer mentally maneuvering pieces on the chessboard, but it’s a gimmicky tactic that he wisely abandons.) But he efficiently articulates Fischer’s petulance, as when the youth loudly berates his mother without a hint of remorse. This kid has no time for sensitivity—he has chess to play.

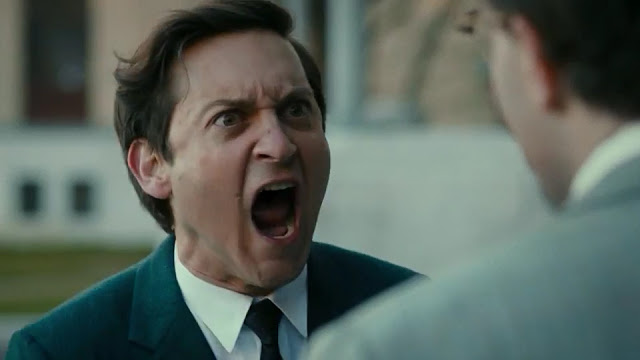

Of course, despite its adherence to the strictures of the sports movie, Pawn Sacrifice isn’t really about chess at all. That becomes clear once Fischer (now an adult, and played by Tobey Maguire in an electric, wildly entertaining performance) is approached by Paul Marshall (Michael Stuhlbarg, great as ever), a self-proclaimed patriot with apparent government influence. There’s a Cold War going on, you see, and Marshall has determined that Fischer is just the galvanizing, blue-collar chap the American people need to see succeed. If he can beat the Russians at their own game in the Championship, his victory will inspire the nation. As for concerns about Fischer’s mental health? Don’t worry, he’ll be fine.

A cynic (as well as a fan of obvious metaphors) might argue that Fischer is a pawn in Marshall’s grand scheme, a helpless lamb to be fattened up and sacrificed at the altar of American exceptionalism. That is certainly the fear of Bill Lombardy (Peter Sarsgaard, pulling an effortless 180 from his jittery turn last week in Black Mass), a chess champ-turned priest who defeated Spassky years ago and whom Fischer selects as his second. (Turns out chess players have seconds. Who knew?) Fischer doesn’t like many people—as with Rick Blaine, he would probably despise you if he ever gave you any thought—but he seems to enjoy Lombardy’s company, grateful to be in the presence of someone who can properly comprehend his genius. It’s a sound choice of companions; if Marshall is the devil sitting on Fischer’s shoulder, Lombardy is undoubtedly the angel, watching over his charge with both collegial admiration and paternal anxiety. Yet Marshall consistently prods Fischer forward—during one of Fischer’s regular episodes of doubt and frustration, Marshall hands him the phone, and who is on the other end but Henry Kissinger, providing words of encouragement—even as the prodigy’s mind begins to fray.

What follows is mostly tried-and-true formula, which means it is both generic and soothing. As Fischer’s “off-field” conduct grows increasingly perturbing (in the film’s best sight gag, he walks through an airport with a paper bag over his head), he faces off against different indistinguishable Soviets in various satellite tournaments, carelessly demolishing them all as the Big Game against Spassky looms. The most interesting of these preliminaries is held in California, where Zwick thankfully opens the movie up a bit. It’s where he introduces Spassky (Liev Schreiber, appropriately restrained), via a glorious shot on a golden beach, the grey-suited champion flanked by an armada of black-clad confederates. It’s also where we meet Donna (Orphan Black‘s Evelyne Brochu), a precocious prostitute who is strangely taken with Fischer. Their brief scenes together—the master of one of the world’s oldest games flirting with the veteran of the world’s oldest profession—may feel imported from another film, but they nevertheless have their own awkward charm, fleshing out Fischer’s brittle humanity while simultaneously underscoring his obsession with chess.

Unfortunately, there remains much of that to play. And despite fine efforts from his cast and crew (Maguire has Fischer wince at every muffled cough from the audience, which the sound design slyly amplifies), Zwick repeatedly bumps up against the limitations of the sports-movie genre, which prove especially constricting in the context of chess. Virtually every scene of match play follows the same regrettable template: Either Fischer or his rival makes a move, followed by a cut to an observer (typically Lombardy or his Russian equivalent) whispering about that move’s consequences. That may be how chess is actually played, but it is not the stuff of compelling cinema. The actors do their best to enliven the proceedings—Schreiber’s look of puzzlement while trying to decipher the intent behind one of Fischer’s moves is more expressive than any line of dialogue—but they cannot surmount the game’s inherent tedium. Stretches of Pawn Sacrifice feel less like a movie than a televised sporting event, and a dull one at that. Playing chess can be stimulating, rewarding, and even thrilling; watching other people play it is simply boring.

Crucially, where Pawn Sacrifice fares better—and where the deceptive guile of Maguire’s performance is so invaluable—is in conveying Fischer’s erratic behavior and abrasive personality. It is well-known that Fischer, who was Jewish, disappeared from public view in the 1970s, only to emerge decades later as a belligerent anti-Semite. Pawn Sacrifice never fully explains how its protagonist degraded from a national hero into a bigoted outcast, but that is by design. It would be facile to attribute Fischer’s mastery of chess to his failings as a person. Instead, Maguire reveals Fischer as a man who, while undeniably brilliant, is also not quite right. Eyes darting everywhere, paranoia mounting after every match, he seems to absorb too much information to process it all properly, as though he is under siege from his own mind. Best known for playing quiet heroes in the Spider-Man films, here Maguire is loud, antic, and, thanks to his deft body language and lack of vanity, simultaneously sympathetic and appalling.

He is, in essence, mesmerizing, but I can’t quite say the same for Pawn Sacrifice. This movie is orderly, sleek, and uncontroversial—everything Bobby Fischer was not. But while it is tempting to envision a more radical encapsulation of this troubled and troubling figure, something bolder and more anarchic, it is unfair to overlook this version’s significant pleasures. It may lack imagination, but it offers us the luxury of spending quality time with quality actors, and it ably evokes the unfathomable mania that surrounded an American chess player in a time of national turmoil. In that sense, its successes offset its failures. Let’s call it a draw.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.