Robert Zemeckis’s The Walk tells the story of Philippe Petit, the French daredevil who one day in August 1974, to the surprise and delight of thousands of unsuspecting New Yorkers, tiptoed back and forth across a wire stretching between the roofs of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Midway through the film, Philippe and two confederates slink into a Manhattan electronics store and ask to purchase an interphone. The proprietor, a sharp fellow named J.P., suggests they buy a walkie-talkie instead, but Philippe refuses, explaining to his comrade in rapid French that cops can listen in on walkie-talkies. This statement raises the eyebrows of J.P., who it turns out speaks French (his initials stand for Jean-Pierre, and he is played very well by the American actor James Badge Dale); he assumes that this motley crew is intent on robbing a bank, and that they’re in dire need of some help.

Strictly speaking, J.P. is wrong—Philippe has no plans to steal anything, except perhaps a few moments of immortality. But in cinematic terms, J.P. is on the mark. The Walk, in its elemental form, is a crime caper. Its story, which it tells with considerable glee and marginal distinction, is that of a gang of lawbreakers who conspire to evade police detection and carry out a seemingly impossible objective. In this way, it is a successor to classic heist pictures like Rififi and Ocean’s Eleven. What distinguishes this one is that, where most capers thrive on the planning of the crime rather than the actual execution, The Walk achieves its power in depicting Philippe’s improbable, death-defying triumph. For the majority of its runtime, it’s a fun, frothy film: nicely acted, convincingly staged, and thoroughly familiar. Then Philippe steps out on that wire, and this modest, unmemorable movie becomes unforgettable.

Of course, one does not simply rush out onto a 1,362-foot-high wire without undertaking the proper preparation. And The Walk takes great pains to illuminate just how Philippe pulled off his extraordinary achievement, examining both his specific temperament and the feat’s overall logistics. We first meet Philippe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt, in a nimble and winning performance) standing in the torch of the Statute of Liberty, a spot Zemeckis returns to throughout the film, where his hero fulfills the role of cheery narrator. We then flash back a few years to Paris, where Philippe’s work as a street performer earns him pennies, along with the ire of his father. He also receives scorn from Papa Rudy (Ben Kingsley, on cruise control), a legendary circus leader who eventually becomes Philippe’s reluctant, wise mentor. Despite some mishaps, Philippe is undaunted in his quest to become the world’s preeminent wire-walker.

So far, so dull. If you ignore Philippe’s peculiar skill set, his obsession with his art initially feels somewhat generic. After all, The Walk is about—and stop me if you’ve heard this one before—a man who has always had a dream. But even if Philippe occasionally comes across as a construct, Gordon-Levitt makes him immensely likable, and Zemeckis stages his early exploits with style and ingenuity. He remains the rare director who can properly capitalize on the potential of 3-D beyond the usual bombastic set pieces. One of the film’s conceits is that Philippe is constantly on the lookout for stationary objects where he can hang his wire, and Zemeckis (working with cinematographer Dariusz Wolski, who shot Dark City), frequently has him eyeball a pair of distant trees or poles, holding up a slender piece of coil to estimate the width between them; in these moments, the 3-D holds that coil in the foreground while simultaneously accentuating the objects in the background, brilliantly communicating the spatial workings of Philippe’s mind. (Many interior scenes, however, remain too dim on account of the glasses, a problem that similarly plagued the Wolski-shot The Martian.)

The preliminary wire-walking scenes in France are jaunty and effective (though Zemeckis rushes too quickly past one of Philippe’s initial conquests, when he scuttles across the spires of Notre Dame’s cathedral), but once Philippe spies a magazine ad announcing the construction of the Twin Towers, his mania sets in. It’s at this point that Philippe begins assembling his crew, whom he terms “accomplices”. This is Caper 101, but Zemeckis curiously proves more comfortable with objects than with people. Philippe briskly romances a fellow street artist named Annie (Charlotte Le Bon), but their relationship is undernourished, with Annie reduced to the boilerplate role of the supportive female. This same lack of definition befalls Jean-Louis (Clément Sibony), a photographer whom Philippe befriends and immediately casts as his chief collaborator but who never develops any real personality of his own. The requisite scenes of fraternal bonding do yield some moments of wry comedy—when Philippe learns that one of Jean-Louis’ recruits is a math teacher who’s terrified of heights, he responds genially, “That’s OK, I’m terrified of algebra”—but they can’t prevent the movie’s supporting characters from appearing one-dimensional.

But The Walk is less about its characters than about their accomplishments. And in detailing the meticulous planning that predicated Philippe’s historic stroll, Zemeckis is scrupulous without ever becoming banal. (For this and many other reasons, The Walk will assuredly be compared to Man on Wire, the Oscar-winning documentary about Petit’s self-dubbed “coup”.) Whether it’s Philippe’s stroke-of-luck recruitment of an “inside man” or Jean-Louis’ inspired use of a bow and arrow, Zemeckis articulates the magnitude of Philippe’s feat through a canny combination of cinematic flair and straight-up reporting. He allows us to become a de-facto member of Philippe’s crew, reveling in the group’s furtive excitement (they seem to be on the constant brink of police discovery) and trembling with their fear.

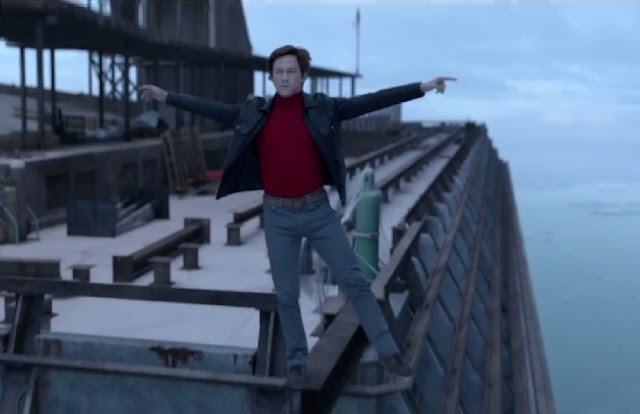

This makes The Walk fun, but Zemeckis is after something more than ephemeral entertainment. In conveying Philippe’s story with such care, he pays tribute to the notion of art as its own form of wonder. Philippe may be insane, but he is not narcissistic. He does not walk across the Twin Towers on a wire simply to elevate his own stature (though that is surely part of it). Rather, he uses his gifts of balance and agility to enchant his audience, to bring joy to those staring in astonishment below. And the final act of The Walk is breathtaking in its scope and simplicity. Armed with amazing special effects and Gordon-Levitt’s effortlessly expressive performance (the actor trained with Petit for the role, not to mention learned French), Zemeckis captures the majesty and madness of Philippe’s walk, emphasizing both the unfathomable danger and the virtuoso talent. There is a moment, in the midst of balancing on his wire in the middle of the sky, when Philippe humbly acknowledges his audience below, and the profound beauty of it makes you—miles beneath him in your seat in the theater—want to stand up and cheer.

Of course, there is also a strain of quiet melancholy percolating through this sequence, the sad recognition that, although we see the fearsome Twin Towers looming before us, we know they can only be remarkably convincing visual effects. Yet the predominant spirit of The Walk is elation, not sorrow. Philippe states repeatedly—to Annie, to us, to anyone—that in order to succeed, he must have absolutely no doubt in himself, to the point that he refuses even to say the word “death”. It’s a fitting sentiment that encapsulates this movie’s confident grandeur, obscuring its minor failings in the process. It is not about death. It is a celebration of life.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.