George Carlin once famously scoffed, “Your house is just a place for your stuff.” But to writer-director Ramin Bahrani, a house is something far more than that. Bahrani, whose previous films include the very good Goodbye Solo (about a gregarious cab driver connecting with his sullen fare) and the very bad At Any Price (about a farmer struggling to keep pace with his competition), makes movies about the existential plight of the common American man. His heroes are hardy, blue-collar folks who nobly toil at their labor while evading the wrath of pitiless institutions, seeking to do little more than provide for their families. That is why, to Bahrani, a house—or, more accurately, a home—is not simply a receptacle. It is instead a birthright, an important symbol of the foundational American dream and a sacred place of familial tradition and honor.

Which makes Rick Carver, the licensed real estate broker at the center of Bahrani’s 99 Homes, something of a bad guy. Actually, that’s being kind. In the context of 99 Homes, Rick is an utter reprobate, the embodiment of corporate greed and inhuman selfishness. We first meet Rick, who is portrayed with snarling relish by the great character actor Michael Shannon, in the film’s electric opening shot, which begins in a bathroom where an anonymous man has just committed suicide via pistol; the camera then glides to Rick and follows him as he strolls through the deceased’s house, barks unsympathetic orders to the sheriff, and heads out into the bright Florida sun before sliding into his luxury sedan. The suicide, we quickly learn, occurred after Rick informed the nominal homeowner that his house now belonged to the bank. Tragic, right? It’s just another day at the office for Rick, who makes his lavish living capably and remorselessly representing various banks, helping to evict residents who have failed to make their mortgage payments and whose homes have entered foreclosure. Though he operates in Florida, he is essentially an instrumentality of Wall Street, a man who executes the will of corrupt and unfeeling conglomerates. He may not be the devil, but he’s basically the devil’s agent.

Where Rick is the undisputed villain of 99 Homes, its less-certain hero is Dennis Nash (Andrew Garfield). Dennis is, at least at first, the quintessential Bahrani protagonist, a down-on-his-luck single father who works tirelessly as a construction laborer to support both his son, Connor (Noah Lomax), and his mother, Lynn (a shrill Laura Dern). The three live in a modest Orlando abode, one that Dennis repeatedly refers to as “the family home” and which is clearly filled with love as well as stuff. But business is slow, Dennis has fallen behind on his payments, and despite his emergency efforts to take legal recourse, one day Rick Carver knocks on his door. The next thing he knows, his furniture is scattered along the curb, and he’s driving his family across town to a cheap motel, where they’re surrounded by fellow victims of the Great Recession.

At this point, you almost certainly feel bad for Dennis, but Bahrani seeks to elicit more than your pity. He wants your rage. At its core, 99 Homes is a blood-boiling screed, and there is something strangely honest in the way it stacks the deck against Dennis so schematically. (To wit: The judge who hears Dennis’s case is unconscionably apathetic.) This movie is not objective, nor is it designed to be. And even if you take issue with Bahrani’s politics, you can still admire his evident passion and acid tone. He cares deeply about this material, and while he may be a bleeding heart, he won’t hesitate to punch you in the stomach.

Though he does hesitate, which is where 99 Homes changes from impressively angry to legitimately interesting. Dennis tracks down Rick and screams at him for awhile; Rick couldn’t care less, but when he gets wind that one of his properties is filled with excrement, he spins on a dime, offering Dennis cash for his assistance. Dennis impresses Rick, not just with his construction expertise but also with his natural instincts as a leader, and lickety-split, he’s a full-time employee of Rick Carver Realty.

You can see where this journey is going, though you probably can’t anticipate the sheer ludicrousness of the destination. But before 99 Homes spirals into a fog of contrivance and melodrama, it serves nicely as a Faustian fable. In working for Rick, Dennis becomes precisely the type of callous individual he so despises, an opportunistic slimeball who views houses as transitory pieces of property rather than consecrated ground. Of course, Dennis constantly reminds Rick that he’s only taking the latter’s money so that he can reclaim his own family home, which is a fairly convincing display of self-delusion. (“Don’t get emotional about real estate,” replies Rick, who rarely gets emotional about anything, except when an underling fails to do his bidding.) And so, 99 Homes slowly plumbs the depths to which Dennis will descend in order to lift himself out of his predicament. He wants to buy his house back, and all he has to do is sell his soul.

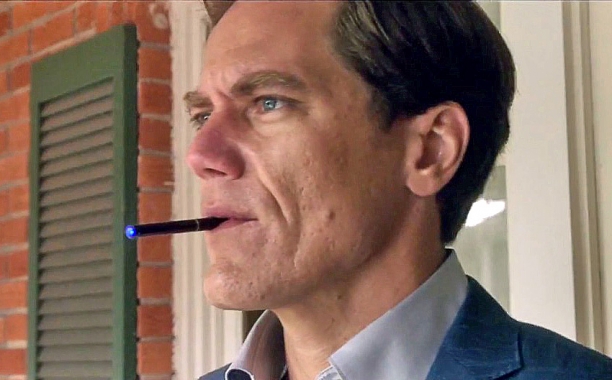

It’s all very black-and-white, or it would be if Bahrani hadn’t cast such talented actors. Garfield and Shannon both excel at locating crevices of dimension beneath flat surfaces, and they provide 99 Homes with more texture than it deserves. Garfield makes Dennis’s dilemma thorny and compelling, polluting his well-meaning drive to support his family with chagrined self-awareness and mounting self-loathing. Shannon, meanwhile, has great fun baring his teeth—Rick is constantly vaping, because that is clearly something evil men do—but he also hints that Rick is simply a product of circumstance; in the movie’s best scene, he delivers a great, swaggering monologue about America’s grotesque financial system and how it transformed him into an eviction maestro.

That’s intriguing, but the nuance of these performances is antithetical to the very essence of 99 Homes, which paints only in stark shades of right and wrong. But don’t worry, any subtlety that Garfield and Shannon supply is dwarfed by the screeching nature of Bahrani’s plotting, not to mention the mundanity of the supporting characters. At one point, Dennis—who has suddenly become flat-out rich—is temporarily stymied from buying his old house back due to red tape (remember what I said about contrivances?), so he instead purchases a McMansion, complete with outdoor pool and cul-de-sac. This allows him to spirit his mother and son away from their dreadful motel accommodations, but when Lynn and Connor tour their new home, they are horrified, and Lynn castigates Dennis for betraying his principles. To repeat: Dennis’s mother and son are disgusted with him because he bought them a beautiful house. As if that isn’t enough, Lynn then flees with Connor to Tampa, which seems problematic; I am not a family lawyer, but I’m fairly certain that a grandmother cannot legally take a young boy away from his father just because the father started earning an increased income.

That is far from the last credulity-straining event in this heartfelt, absurd film. As the sirens start to scream and the bullets begin to fly, it becomes clear that Bahrani has no interest in tempering his homily with plausibility. Yet what really stings about the maudlin conclusion to 99 Homes is that, in restoring Dennis to his dignity, it strips him of his humanity. He becomes a mere puppet, a figurehead for Bahrani’s soapbox theatrics. The director undeniably (and understandably) wants Dennis’s redemption to produce a shudder of catharsis, but he fails to make that catharsis believable or persuasive. That’s the sad irony of Dennis’s predictable arc in 99 Homes. His salvation is the movie’s doom.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.