Money Monster is a fanciful parable rooted in a real-life catastrophe. In December of 2007, the U.S. economy crashed, and the Great Recession began. People lost their homes, their jobs, and a whole lot of their money. The financial markets have since rebounded, but for many, the acrid scent of the collapse still lingers. Attempting to capitalize on this continuing bitterness, Money Monster paints a portrait of Wall Street as a rotted abscess, festering with corruption and venality. You’ve never seen America’s big banks depicted in such an unflattering light. Well, unless you’ve seen The Big Short. Or Margin Call. Or Too Big to Fail. Or Inside Job. Or a newspaper article or blog post that was written at any point in the past eight years.

You get the picture. This movie, which has been directed by Jodie Foster from a script by a trio of screenwriters, isn’t saying anything new. But topicality is hardly a requirement of cinematic worth, and while Money Monster isn’t remotely insightful, it is rarely uninteresting. Some of this is to its benefit: It sports a decent premise, it’s surprisingly funny, and it features excellent actors who take their craft seriously. But the real fascination surrounding this silly, vacuous, ultimately disastrous thriller is of the morbid variety. Watching it, you are compelled to wonder just how a picture of such pedigree could disintegrate into such a puddle of idiocy. Perhaps it’s all a clandestine metaphor designed to mirror the tumultuous nature of the recession itself. It raises your hopes through bluster and recklessness before it crashes—hard.

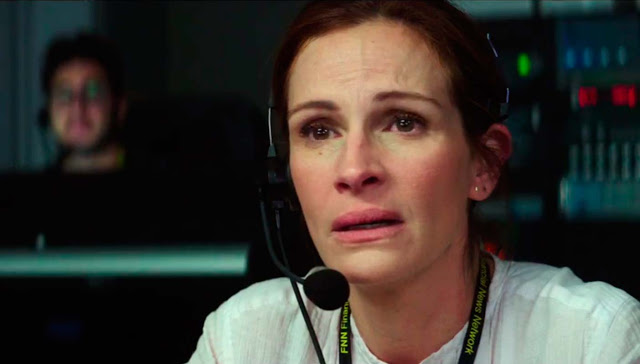

But there’s a rise before the fall, and Money Monster‘s opening passages have an undeniably slick, goofy appeal. George Clooney stars as Lee Gates, an unctuous financial pundit with a daily television show that’s a cross between Mad Money and The Jim Rome Show, as hosted by Howard Stern. He dances, he raps, he wears ludicrous costumes laden with phony bling, and he regularly smacks a giant red button on his desk to introduce an obnoxious video clip or sound effect. His director, Patty Fenn (Julia Roberts), watches from the booth with a weary mixture of admiration and resignation, attempting to keep the show from careening out of control as her pompous star leaps from one improvised bit to the next.

It’s tempting to envision a different version of Money Monster, one that operates as a character study of these two showbiz souls, dissecting their yin and yang. As it is, we at least get a glimpse of just how pathetic a person Lee is, and how helpless he feels. Clooney is often criticized (wrongly, in this critic’s view) as an actor who simply coasts on his natural charisma, but he counteracts that impression here, playing Lee as an oblivious gasbag who can’t comprehend the hollowness of his own success. Lee is cocky, juvenile, and just a smidgeon desperate—watch as he boasts about how he hasn’t eaten dinner alone in years—but Clooney doesn’t oversell it. It’s nice to see him playing a gigantic doofus outside of a Coen Brothers film.

But the incarnation of Money Monster that we do have is a hostage thriller, not a drama. As the film opens, Lee’s show is interrupted by Kyle Budwell (Jack O’Connell), who, after posing as a delivery driver, sneaks on set and brandishes a gun. (That an armed man can simply waltz onto the set in a crowded television studio without anybody noticing him is actually one of this movie’s more plausible happenstances.) After proving that his weapon is loaded, Kyle reveals that he’s a disgruntled investor who recently squandered his savings on one of Lee’s bogus stock tips, and he’s not too happy about it. He forces Lee to don a suicide vest; he also informs Patty that he possesses the vest’s detonator and that he’ll set off the explosive if she cuts the live feed. (Apparently, Lee performs his shows live rather than taping them—remember what I said about plausibility?) Kyle has something to say, and he demands an audience.

There’s potential here—after all, a hostage crisis served as the template for Sidney Lumet’s classic Dog Day Afternoon, and even F. Gary Gray’s The Negotiator (with Samuel L. Jackson and Kevin Spacey) mostly worked as a sturdy crime procedural. So it’s almost impressive how badly Foster squanders the promise of Money Monster‘s conceit. This is the legendary actress’ fourth feature as a director, and her first since The Beaver, which starred Mel Gibson as a American man who, after an apparent psychotic break, begins speaking exclusively through a hand puppet, complete with Cockney accent. The Beaver was strange and heavily flawed, but it at least possessed a strong narrative through-line, and you sensed that its maker was in control of its material, no matter how ridiculous.

Money Monster is a different kind of mess. It lacks any sense of authorship, as though Foster thought that she could rely on the caliber of her actors and the themes of the script to disguise her own filmmaking neglect. Whatever the reason, the execution here is downright risible. Scenes never seem to play for the proper length, either cutting before they develop any momentum or lurching on far past their expiration date. The editing is patchwork, such that some sequences appear to have been inserted out of order. Even the blocking frequently seems off, an irony for a movie in which a character is constantly directing cameramen to provide different types of coverage.

And yet, despite all of these errors in technique, the movie’s first half is not devoid of pleasures. It works best as a black comedy, with Lee and Patty feebly leaning on their television expertise in an effort to mollify a deranged viewer. (There’s a very funny throwaway gag where, after Lee curses, a technician winces aloud, apparently more concerned about an F-bomb going off over the airwaves than with a real bomb going off 20 feet away.) Emily Meade provides an unexpected blast of energy as Kyle’s girlfriend, who shows up, then erupts, delivering a tirade that would be right at home on an entirely different type of daytime television show. And the movie achieves a sort of mad genius during a scene where Lee tries to extricate himself from his predicament the only way he knows how: by transforming the entire ordeal into just another stock tip.

And then… look, it’s unfair to judge a movie too harshly for a bad ending. Ending a movie is hard. The problem with Money Monster is that its ending begins at the rough one-hour point, at which point it abandons its sense of inane fun and instead just becomes eye-poppingly stupid. There are plot twists, fake phone calls, inadvertent gunfire, didactic mumbo-jumbo about algorithms, and hackers who talk like Yoda. Dominic West arrives as an oily CEO, while Outlander‘s Caitriona Balfe furrows her brow as his hoodwinked PR lieutenant, and while it’s always gratifying to see two stars of prestige TV drama getting paid, it’s also difficult not to feel sorry for them as they spit out clumsy dialogue and check their respective watches. (Speaking of prestige television, the rote squabbling here between Giancarlo Esposito and Chris Bauer as police officers—one sensible, the other irritatingly thick-skulled—now has me longing for a series where Gus Fring hangs out with Frank Sabotka.)

But no one deserves more pity than Jack O’Connell. Primed to go supernova after his terrific performances in ’71 and Starred Up (along with his solid leading-man work in Unbroken), the English actor surely couldn’t pass up the prospect of working alongside American screen royalty. But while O’Connell gamely throws himself into the role of Kyle (complete with a scraggly beard and New Yawk accent), he’s doomed from the start. Kyle is Money Monster‘s idea of an everyman, which means he’s erratic, sullen, dimwitted, and prone to spasms of violence. He isn’t a real person—he’s just a construct, a shrill and reductive effort at symbolizing the pain felt by so many blue-collar folks across the country. That the film endeavors to depict him as a tragic hero reveals both the absurdity of its writing and the emptiness of its politics.

Early in Money Monster, Lee offers to make his captor financially whole, a gesture that Kyle angrily rebuffs. Instead, he seethes, “I want an explanation.” So do I. In particular, I’d like to know how a movie directed by an accomplished actress, starring a phenomenally talented cast, and featuring an intriguing premise could crumble into such a debacle. Per the demented logic of Money Monster, the surest way for me to receive satisfying answers to my questions would be to stroll into the offices of TriStar Pictures, whip out a gun, and take the film’s producers hostage. But that sounds like a lot of work, and as it turns out, I’m not as noble as Kyle. He seeks to understand how he was swindled. I just want my money back.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.