One of the many running jokes in 2003’s Finding Nemo—that magnificent maritime adventure from Pixar Animation Studios—was that its main character, Marlin (voiced by Albert Brooks), was a clownfish but was spectacularly unfunny. In fact, Marlin was a neurotic grump, far more prone to panic than humor. He’s still grousing about anything and everything in Finding Dory, but one of his complaints stands out. “Crossing the entire ocean is something you should only do once,” he grumbles. It’s a gripe that might as well be chum to metaphor-hungry film critics—not that I have anyone in mind—looking to compare this sequel to Finding Nemo, which remains one of Pixar’s greatest achievements. The computer-animation pioneer is renowned for many things—breathtaking visuals, witty dialogue, mature themes smuggled inside kid-friendly packages—but perhaps its defining trait is its commitment to originality. This is, after all, the studio that has told tales of culinarily gifted rats, silent robots, and anthropomorphized emotions. Which brings us back to Marlin’s gloomy, profound question: Is it really worth crossing the ocean twice? That is, can a straightforward sequel really be worthy of joining the animation giant’s formidable canon?

Yes and no. What, you were expecting a straight answer? Fine, I’ll be blunt: Finding Dory is not as good as Finding Nemo. Yet even that seemingly straightforward assessment comes with a caveat, namely: so what? Comparing sequels to their originals is a reductive way of evaluating them on their own merits; that’s especially true when said original is one of the best movies of the prior decade. Finding Dory may, er, swim in the shadow of its progenitor, but that shouldn’t preclude us from weighing its standalone value as a movie.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. On its own terms, Finding Dory is, well, pretty good. The problem is that, as much as I may strive to, I can’t really judge it on its own terms. It is virtually impossible to watch this movie and not reflexively measure it against its peers—not just Finding Nemo, but the entire Pixar catalog. And in that context, “pretty good” isn’t quite good enough. Finding Dory has much to recommend it—its animation is sublime, its characters are well-drawn, and its themes are thoughtfully articulated and genuinely poignant. Yet it lacks that spark of magic that powers the studio’s grandest feats. It’s second-tier Pixar: enjoyable, but not extraordinary.

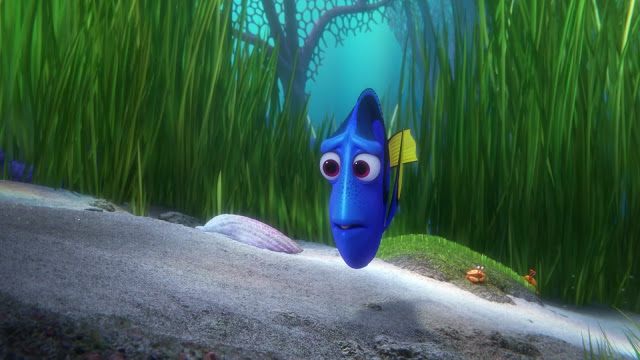

It does have Dory, however, and that counts for plenty. You remember Dory, right? She doesn’t remember you. Voiced once again by Ellen DeGeneres, Dory is a jovial blue tang who suffers from short-term memory loss. That’s a condition that could cripple a less resilient individual (recall the spiritual disintegration that befell Guy Pearce in Memento), but Dory is blessed with an indefatigable cheerfulness that is both admirable and infectious. Her handicap creates a rich vein of comedy, one that the movie mines effortlessly and repeatedly; somehow, the recurring joke of a memory-addled fish losing her train of thought never grows tiresome. But Dory is no mere punch line. She’s a true role model: generous, persistent, and unflinchingly brave. Marlin could learn a few things from her.

That he hasn’t is one of Finding Dory‘s more conventional touches—though it picks up a year following the events of Nemo, the sequel places its characters roughly where we left them. Marlin remains anxious and judgmental, which makes him both a terrible and a perfect friend for Dory, who graciously tolerates his curmudgeonly attitude and occasionally draws out his inner strength. It turns out, however, that Dory has issues beyond her disability. As we learn during the film’s sweet, sad prologue, she was separated from her parents when she was young, and now a memory of them has rushed back into her consciousness, compelling her to look for them. Following some pointed nudging from Dory, Marlin and his son, Nemo (Hayden Rolence, doing a convincing imitation of the now-grown Alexander Gould), agree to accompany her on her journey, which takes them to the sun-dappled shores of California.

The title suggests that we’re in for a replication of the first movie’s search-and-rescue story, but while the sequel does occasionally feel like a retread, it’s less about finding Dory than it is about Dory finding. But finding what? The ostensible object of her quest is her parents, but Finding Dory is also a tale of self-discovery, with Dory first learning the limitations of her abilities and then comprehending the depths of her pluck and resourcefulness. Besides, if you’re going to recycle an old plot, there are far worse blueprints to follow than the one that director Andrew Stanton (also writing here, along with Victoria Strouse) created with Finding Nemo. So yes, once again we find ourselves on a thrilling adventure, meeting colorful characters, seeing dazzling sights, and racing to recover a missing fish (it’s hardly a spoiler to reveal that, at some point, Dory gets isolated from Marlin and Nemo). Gee, bummer. In all seriousness, to perceive such familiarity as inherently harmful is to place too high a premium on novelty while failing to appreciate quality storytelling.

To say nothing of resplendent imagery. It has become almost tedious to extol the astonishing aesthetics of every new Pixar release, but the ocean of Finding Dory demands particularly lavish praise. Shafts of sunlight pierce through the water, motes of dust and fragments of kelp float through the frame, and everything rocks gently to the perpetual, soothing rhythm of the waves. Stanton and his animators capture the constant motion of aquatic life—something in the frame is always rippling, even if the characters are still—but the camera is focused rather than frenetic. Even the 3-D is expertly employed, subtly enhancing depth of field to create an expansive, enveloping environment. As always with Pixar, this level of care extends to the characters, in particular Dory, whose pale-lavender irises serve as windows into her tender, buoyant soul.

The real showstopper, however, is Hank (Ed O’Neill). A sort of chameleonic octopus (though as Dory points out, his missing tentacle actually makes him a septopus), Hank meets Dory at the Marine Life Institute, a Sigourney Weaver-run facility that doubles as her parents’ last known whereabouts. Hank’s disposition could charitably be described as acidic—he makes Marlin seem gregarious by comparison—and all he really wants is to be shipped off to an aquarium in Cleveland. (Regarding the desirability of living in Cleveland, recall that Finding Dory was made prior to last week’s NBA Finals.) Circumstances conspire such that Hank and Dory form a tentative alliance, resulting in some of Pixar’s finest animation yet. Similar to Randall in Monsters Inc., Hank can blend into his surroundings, which leads to some very clever and deceptive imagery of the “Where’s Waldo?” variety. Able to breathe both in and out of water, he moves unlike any other character in the film, squelching his way from one area to the next, and Stanton and his team render his maneuvers with uncanny precision. Hank may be a sourpuss, but he sure looks sweet.

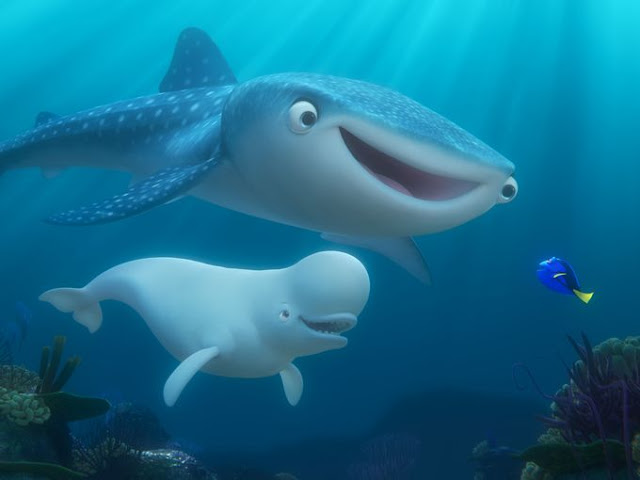

If only he were headed toward a more interesting story. Nothing in Finding Dory‘s narrative is bad, exactly. (That’s literally true of the characters; with the exception of a cameo from an angry giant squid, there isn’t a villain in sight.) But the screenplay simply lacks that trademark verve and wit that distinguish Pixar features from similar animated fare. Everything just feels slightly off. Most of the supporting characters—a pair of territorial sea lions, a spacey common loon, an insecure beluga whale—are cute, but they aren’t quite as funny or distinctive as they’re designed to be. (A happy exception is Destiny, a myopic whale shark who shares a history with Dory.) Weirdly, this blurry sense of impersonality even extends to Marlin and Nemo, who seem to be on hand more to propel the plot than to deepen the emotions or enrich the themes. That plot is reasonably satisfying, but it is also predictable and contrived. And while there are some good laughs, much of the humor lacks sharpness, settling for juvenile gags rather than well-constructed jokes.

This is not to deny the strength of the movie’s message. Finding Dory is at times a powerful meditation on the importance of friendship and family, as well as an appreciation of the value in embracing your differences rather than running from them. But although that’s a noble lesson to teach children, it can’t quite compensate for Finding Dory‘s curious atmosphere of ordinariness, a sense that it could have been made by anyone. That’s most evident during the third act, which is hectic, dubious, and eventually just plain silly. Yet while that scattered climax is the nadir, the film is more deflating for its absence of highlights. As much as I took pleasure in watching the majority of this movie, I kept waiting for that burst of ingenuity, that moment of inspiration that announced it as a true Pixar product—something akin to the furnace scene in Toy Story 3 or Dory’s own “I’m home” speech from Finding Nemo. It never came.

More than once, a character in Finding Dory asks, “What would Dory do?” Good question. If she watched this film, she would almost certainly admire it, in particular its bright colors, its fleet pacing, and its lovely Thomas Newman score. And then, as with most things, she would forget it. Sadly, I suspect that I will do the same.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.