At one point in Jurassic Park, Sam Neill attempts to evade a T-rex by hiding in plain sight. His theory—supported by years of paleontologic research—is that the dinosaur’s visual acuity is based on movement, so it won’t detect him if he stands stock still. It’s a riveting scene (most scenes in Jurassic Park are), forgoing the kineticism of the typical chase (“must go faster”) in favor of terrifying immobility. Don’t Breathe, the taut and accomplished new chiller from Fede Alvarez, essentially extends this concept to feature-length. It’s a horror movie that bottles the genre’s rushing adrenaline and redirects it inward; here, rather than running away, the only way the characters can escape the monster is by being very, very quiet.

That monster—the film’s tyrannosaur, if you will—is Stephen Lang, the grizzled television actor who briefly lit up the big screen in 2009, with colorful parts in Public Enemies, The Men Who Stare at Goats, and (most memorably) Avatar. In the latter, he played a bloodthirsty warmonger named Miles Quaritch; his heavy in Don’t Breathe makes Quaritch seem positively pacifistic. Here, he portrays an unnamed, solitary Iraq war veteran who owns a modest two-story home, a surly rottweiler, and an even surlier disposition. As soon as you see him in the cold open dragging a bloody body down a deserted street—an ill-advised flash-forward that dilutes the movie’s considerable tension—you can see the darkness in his soul.

But he can’t see yours. The tantalizing hook of Don’t Breathe is that its villain isn’t your run-of-the-mill slasher—he’s a blind man. He’s also a mark for the movie’s nominal heroes, a trio of teenagers living in impoverished Detroit who moonlight as amateur thieves, breaking into abandoned homes and stealing random valuables. (In this sense, Don’t Breathe recalls Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, if glimpsed through a cracked mirror.) They include Rocky (Jane Levy, a dead ringer for Elisabeth Moss), her boyfriend Money (Daniel Zovatto), and their friend Alex (Dylan Minnette), whose father runs a security company, granting them illicit access to keys for houses across the neighborhood. Frustrated with the crew’s meager scores—Alex insists that they never steal currency and that they limit themselves to ten thousand dollars in goods to avoid exposure to a grand larceny charge—Money perks up when he hears from his fence that some old guy in town is sitting on nearly half a million in cash. A few days later, these unsuspecting delinquents are at the blind man’s door, Rocky wriggling her way through an upstairs window before shutting off the alarm. From there, it’s just a matter of finding the loot without disturbing the sleeping owner. I know you’ll struggle to believe me, but something goes wrong.

The opening act of Don’t Breathe is tidy and efficient, even if it also demonstrates that Alvarez isn’t especially interested in characters. To be fair, his script, which he wrote along with Rodo Sayagues (who also co-wrote Alvarez’s ill-received Evil Dead remake), makes a token effort to define these youths—Rocky is a well-meaning person who longs to emancipate her younger sister from their vulgar mother, Alex is a smart and diffident kid who carries a torch for Rocky, and Money, well, Money is just a one-dimensional asshole—but his heart isn’t in it. He’s here to scare, not care.

Which is fine. Alvarez’s minimalist approach allows him to quickly get to the good stuff, and once the burglars are in the house, he goes to work. For such a gleefully nasty movie, there’s a surprising degree of elegance in his filmmaking; a single-take sequence where the camera drifts through the blind man’s house, tracking the various thieves as they search its countless rooms, is a moment of inspired directorial bravado. It’s midnight madness by way of Robert Altman.

It is hardly a spoiler to reveal that, in short order, the blind man wakes up, at which point Don’t Breathe gets down to business. Remarkably, for such a simple premise—the latter two-thirds of the film essentially boil down to “blind guy chases teens”—Alvarez maintains a high level of suspense, continually tweaking his claustrophobic template with inventiveness and wit. He also puts a sly and novel spin on the usual horror conventions. I’ve seen plenty of movies where a woman has to frantically crawl through a narrow air duct (see: 10 Cloverfield Lane), but never where she’s being chased by a rottweiler shimmying its way after her. (That poor pooch deserves a raise; a scene where it attempts to attack someone in a locked car is indecently nail-biting.) And while every serial-killer flick features potential victims trying to hide from a ruthless murderer, this is the first where someone does so by flattening himself against a wall as his pursuer strides blindly past him.

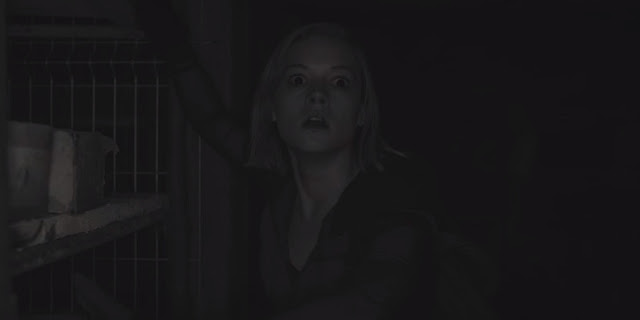

That’s the real key to Don’t Breathe: It makes brilliant use of its villain’s sightlessness, which it treats as both a disability and a superpower. The blind man may be unable to see, but he can still detect his surroundings, and Lang hammily plays up his sniffing and his snarling, suggesting a demon with enhanced senses. This means that Alvarez can make the movie scary without resorting to the queasy sadism that so many horror directors rely on. He doesn’t use “Boo!” moments to shock his audience; he uses them to feed information to his characters. In the suffocating silence of Don’t Breathe, the slightest noise—the creak of a floorboard, the vibration of a cell phone—is a dead giveaway, emphasis on “dead”. By the time the blind man turns off the lights and plunges the teenagers into absolute darkness—an evening of the playing field that obviously recalls the climax of The Silence of the Lambs—you’ll be holding your breath right along with them.

In one of Don’t Breathe‘s more iconic images, a character lies sprawled unconscious atop a skylight, the glass beneath him slowly beginning to crack under his weight. It’s a moment that nicely summates Alvarez’s canny style, his ability to take a straightforward conceit and stretch it to its breaking point. Don’t Breathe finds variety amid its terror—there’s one legitimately jaw-dropping twist, and I haven’t even mentioned the diabolical turkey baster—but it’s really just about generating constant white-knuckle tension. I can envision critiques regarding its lack of depth, but I advise those critics to take after this movie’s characters. In other words: hush.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.