There have been bloodier war movies—grisly productions committed to depicting the visceral horror as bullets tear through flesh. And there have been more provocative war movies, those that reenact armed conflict to make a political statement on its nobility or its lunacy. But there has never been, in my estimation, a war movie of such relentless, gripping intensity as Dunkirk, Christopher Nolan’s stunning World War II epic. The adjective “white-knuckle” has wilted into cliché, but as someone who spent the majority of this film with his fists clenched in involuntary apprehension, allow me to offer a word of advice: Before seeing Dunkirk, clip your nails. Otherwise, you’re liable to tear them right off.

The sheer magnitude of Dunkirk feels unprecedented, but it’s in keeping with a director who has made a career of smuggling brainy, stimulating ideas inside packages of overpowering brawn. Size matters to Nolan, and not just in the way you might think. Yes, Dunkirk is a gigantic film, shot extensively on 65-millimeter IMAX cameras, which help convey the enormity of its scale. (For the record, I watched the film projected in non-IMAX 70mm, though I intend to make a trip to the IMAX for round two.) But even as he’s painting on a sprawling canvas—showing you the vastness of a beach, the infinite reach of an ocean—Nolan is simultaneously compressing the carnage, paradoxically resulting in an expansive claustrophobia. Consider an early scene on the title city’s famous coastline: Thousands of soldiers scattered along its sands freeze in unison, their ears picking up the faint whine of an approaching German bomber. The horizon seems endless, but there’s nowhere to go. As the plane zooms past overhead, all they can do is flatten their bodies and cross their fingers.

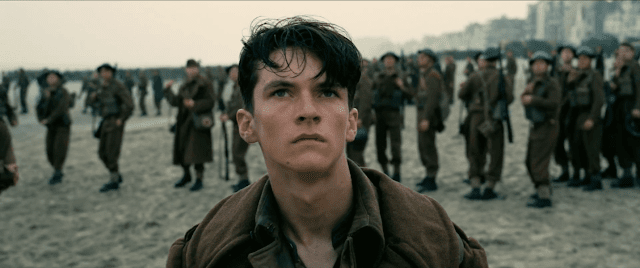

One of those soldiers is Tommy (Fionn Whitehead, boyish and sympathetic), the putative protagonist in a movie less concerned with individual personalities than with collective coordination and chaos. To the extent that Dunkirk has a flaw, it lies in its lack of the kind of achingly human center that grounds Nolan’s grandest films in such tangible desire and despair—something akin to Guy Pearce’s forgetful gumshoe, Leonardo DiCaprio’s obsessive dreamer, or Matthew McConaughey’s grief-stricken pilot. Here, Nolan articulates war primarily as a collaborative struggle, so much so that his screenplay barely bothers to name its characters.

But even if Dunkirk declines to ensnare your heart with a tragic person, it remains deeply invested in people, and in exploring the toll that war exacts on the human psyche. It’s a study in the inherent tension between Darwinian instincts and martial solidarity. There are passages of anguish, as when a shell-shocked officer lashes out at a rescue boat captain for returning to the site of his trauma, or when a handful of would-be stowaways conclude that their beached vessel needs to offload weight in the form of fellow soldiers. But while Dunkirk never flinches from warfare’s horrors—amplified tenfold by the excruciatingly realistic sound design, and by Hans Zimmer’s extraordinary, fever-pitch score—it is nevertheless the work of a devout humanist. This is a profoundly hopeful film that happens to chronicle a seemingly hopeless situation.

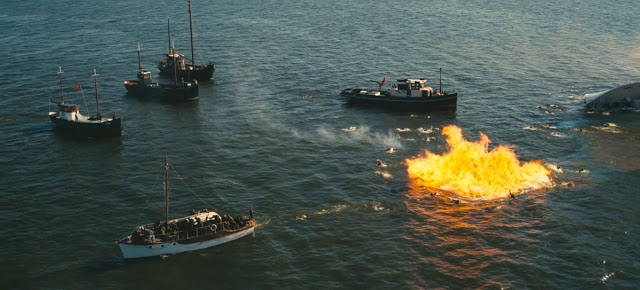

About which: Dunkirk’s premise is refreshingly uncomplicated. It recreates the famous evacuation of 1940, when roughly 400,000 soldiers—British, French, and Belgian—found themselves stranded on a beach, their backs against the Atlantic, with Nazi forces closing in. This means that, for all its majestic images and sweeping emotions, Dunkirk is essentially a movie about a giant logistical challenge. The British Army wants to ferry its boys home. How can it do that when the Germans are bombing its men from above, sinking its boats from below, and generally thwarting its every maneuver?

Dunkirk broadly answers this question—by the time it ends, we have a basic understanding of what happened, and how—but it does so through intimacy rather than by resorting to clumsy docudrama. Apart from a terse opening title card, the film is virtually devoid of exposition; refusing to hold your hand, Nolan instead shoves you into his gilded nightmare, making you taste his characters’ sweat and absorb their terror. This can make Dunkirk’s narrative disorienting, especially early on, when you’re scrambling to keep up with its frenetic pace and whirlwind of new faces. Yet while the film may be busy—it’s remarkable how much incident Nolan packs into his 106-minute running time—it’s never choppy. As a director, Nolan may be a visionary, but as a writer, he remains scrupulous.

And while Dunkirk is a staggering visual and aural achievement, what really makes it special is its structure. In an audacious gambit, Nolan has devised the movie as a triptych, with three overlapping segments that all occupy convergent time frames. The first, subtitled “The Mole” (better known to this layman as a large pier), follows Tommy and a handful of soldiers he meets, and it spans one week. The second, called “The Sea”, tracks Dawson (Mark Rylance, splendid), a civilian who decides to sail his motorboat across the English Channel to help with the retreat; it covers the evacuation’s last day. And the third, “The Air”, takes place entirely in the sky, where a Spitfire pilot, Farrier (a miraculous Tom Hardy), attempts to provide air cover during the retreat’s final hour.

Had it progressed linearly, Dunkirk probably would have worked just fine, but its fractured chronology lends it an electrifying kick. For one thing, it reinforces the film’s commitment to point of view, showing everything through the eyes of its disparate principals, each of whom possesses limited information. This adds to the movie’s vérité feel, placing you inside the characters’ headspace and forcing you to puzzle things out along with them. But it also contributes to Dunkirk’s steamrolling accumulation of emotional power. Because the threaded narrative continuously loops back on itself, it depicts a number of events twice, but from different perspectives. As a result, certain sights—a wave of a hand, a wrecked vessel, a whoosh of planes flying overhead—acquire new and cathartic meaning when glimpsed a second time. (For this reason—and as is true with many Nolan films, particularly The Prestige—the movie is certain to reward multiple viewings.) Admittedly, in terms of raw comprehension, the latticed construction isn’t quite as clear as it could have been. But Nolan’s chief goal here is not clarity. It is awe.

And to borrow some slang from Nolan’s homeland, by golly does Dunkirk deliver that. Most war movies—even the great ones, like Saving Private Ryan—tend to toggle between high-octane set pieces and more muted stretches of dialogue and preparation. Here, everything feels like a set piece, resulting in a sensation of perpetual, agonizing suspense. (It is in this regard that the persistent throb of Zimmer’s score is so effective.) In one scene, Tommy and a comrade are forced to run across a narrow plank while carrying a wounded man on a litter, the surrounding soldiers eyeing them like a crowd watching a golfer lining up a putt. In another, a downed pilot scrambles to crack open his escape hatch as water floods the cabin, and you may start to experience shortness of breath. Even mundane actions, like scrawling a number with a piece of chalk or methodically cranking open a landing gear, are endowed with tension. Ships capsize, men drown, oil bursts into flame, and all the while Nolan watches, his 70-millimeter print affirming both the grandeur of film and the grotesque absurdity of war.

It’s almost too much to bear. But again, there is a gentle undercurrent of optimism running through Dunkirk, as it examines how brave men stared down death with dignity and resolve. In communicating this shared valor, all of the actors are capable and convincing, but I would be remiss not to single out Hardy. Working with Nolan for the third time, the chameleonic performer is blessed with handsome features and sinewy physicality, so of course his director straps him inside a cockpit and obscures his face with a mask. Few could cobble together anything of note with those constraints, but Hardy—who previously showcased his ability to do a lot with little in Locke—can do more with an eye flit than most actors can with a scream. He invisibly expresses Farrier’s internal thoughts and somehow, through the accretion of tiny gestures, builds him into a tragic hero. In a scene where he repeatedly glances at his fuel gauge before making a momentous decision, very little actually happens, but it still feels like the stuff of triumph.

The restrictions facing Hardy as an actor are, of course, nothing compared to the oppressive fear that suffocates the film’s characters, especially those trapped on the mole. In this movie, safety is an illusion, and catastrophe is just a fired torpedo or a dropped bomb away. It’s small wonder that when Tommy’s newfound friend boards a destroyer—his ostensible passage to freedom—the first thing he does is start poking around for the exits. But there is no escaping Dunkirk. This is a film whose intensity builds and builds and builds, shackling you to your seat with its might and its craft. The men on that beach made history, and with Dunkirk, Nolan has paid them magnificent homage. In so doing, he’s made his own mark in the annals of film, providing a towering reminder that cinema—that ever-malleable medium of infinite artistic possibility—shall never surrender.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.