A daub of acid on an exposed nerve, Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane is a charmingly nasty piece of work, full of rich colors and garish shocks. It’s a proudly ridiculous B movie, one with little sense and lots of blood. Soderbergh has made far better films—just last year, he delivered Logan Lucky, a spry and surprisingly tender heist picture—but it’s still exciting to watch him dispense with any semblance of sensitivity and just slather on the gory carnage.

With the exception of the Ocean’s Eleven movies, no two Soderbergh productions are alike. Yet his restless career has followed something of a pattern, toggling between quirky, experimental features (Full Frontal, Bubble, Che) and more brusque genre fare (Haywire, Contagion, Side Effects). Unsane may be his first film that falls into both camps. In terms of plot, it’s pure pulp, a grisly tale of violence and murder. But while Soderbergh typically flaunts his smooth craftsmanship when making mainstream material, Unsane is different, carrying none of the elegant polish that heightens the Ocean’s films. Instead, it looks cheap and DIY, almost as though it was shot on an iPhone. Which, of course, it was.

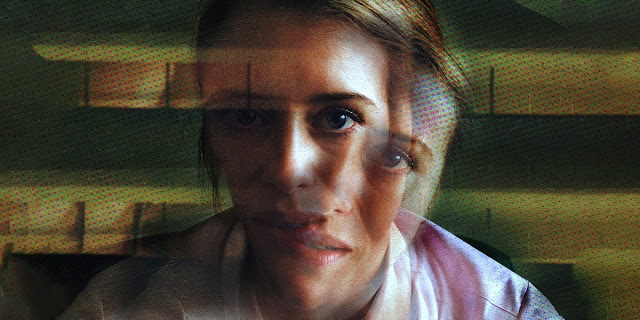

Yes, the legendary Steven Soderbergh—Palme d’Or winner and three-time Oscar nominee—has made a feature-length movie using a fucking smartphone. And perhaps the most impressive and disturbing thing about Unsane is how credibly it passes as a major studio production. Sure, the image tends to have a waxy, hyper-digital look, and the slightly boxy aspect ratio feels a little weird. But there are no nauseating whip pans, and only a few juddery following shots. The framing is confident and generally precise, and the extreme close-ups feel natural rather than invasive. Soderbergh has called the iPhone the future of movies, and watching Unsane, it’s easy to imagine a horde of ambitious wannabe directors grabbing their cells and churning out films that are as artistically fertile as they are economically frugal.

Except, it’s unlikely that those newcomers will possess Soderbergh’s inveterate skill, his gift for making filmmaking look easier than it is. And Unsane is probably as good as an iPhone-helmed movie can possibly look, thanks to its crisp editing and steady blocking. (As ever, Soderbergh shot and edited the picture himself, under pseudonyms.) It’s most striking for its use of primary color, in particular various shades of blue; a late tête-à-tête in a small, unfurnished room pops off the screen thanks to the deep cobalt of the walls and the floor. It hardly seems accidental that the movie opens with an unspecified narrator waxing poetic about the color, recalling fondly just how beautiful the object of his affection looked in blue attire when they first met.

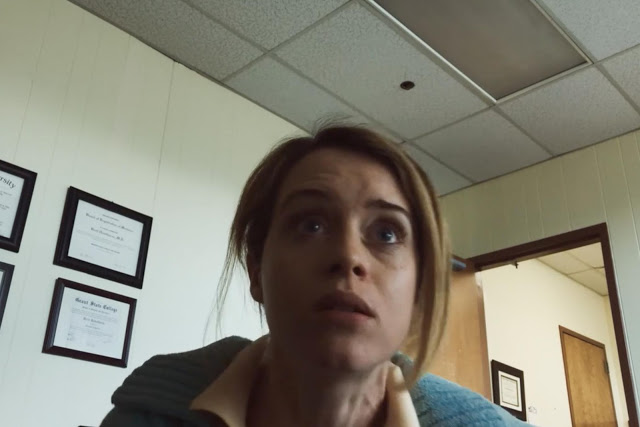

The identity of that narrator remains a mystery for some time; instead, Unsane centers on his crush, Sawyer (Claire Foy). As we learn from the film’s brisk early scenes, Sawyer is a Type A businesswoman, slicing through those around her with purposeful ferocity. Whether she’s deftly deflecting the advances of an overeager superior or effortlessly picking up a slab of beef in a bar, it’s plain that she operates from a position of complete control.

Until she doesn’t. Turns out, Sawyer is a recent victim of stalking, and she constantly sees her menacer’s bearded face in the visage of total strangers. Resolving to get help, she visits a pleasant therapist at an inviting facility called Highland Creek. After a brief but productive chat, Sawyer agrees to future appointments, a seemingly healthy decision that will help her cope with her trauma. Now, if she could please just fill out these boilerplate forms…

If there’s a lesson to Unsane—well, a lesson beyond “beware of doctors with facial hair”—it’s to read the fine print. By casually signing those forms, Sawyer has “voluntarily” committed herself to Highland Creek, an ostensibly cheery clinic that’s actually an asylum. Whoops! Surely this is all just a silly mistake, one that can be rectified with a simple phone call. But the harder Sawyer tries to leave the premises, the deeper she descends into its bowels. This is especially problematic because she insists that one of the doctors, a smiling chap played by mumblecore guru Joshua Leonard, is the very same stalker who’s been terrorizing her these last few restless months.

Is Sawyer’s life really in danger, or is she simply the victim of her own paranoid delusions? The best stretch of Unsane teases out this question, forcing you to question Sawyer’s sanity and reliability even as you grimace in horror at her predicament. While you puzzle that out, there is quite a bit else to chew on. This includes a half-hearted attempt to scold the health-insurance industry, which—as Sawyer discovers thanks to a friendly fellow resident (Jay Pharoah) who conveniently keeps a clandestine cell phone—incentivizes sham shops like Highland Creek to hold patients against their will. Sawyer must also navigate the peculiar codes and rituals of the asylum, including warding off the violent attentions of Violet (Juno Temple, having fun). Amy Irving pops up as Sawyer’s mother, brought in to advance Sawyer’s case and the plot, while a certain movie star and Soderbergh vet appears in a pointless flashback, just to send the audience into appreciative titters. And there’s perhaps a whiff of #MeToo topicality in the story of a society whose instinct to blame female victims of assault is so ingrained, it extends to throwing them in the loony bin.

None of this is especially persuasive. As Unsane grows increasingly outlandish, it forfeits any interest in being taken seriously. But even though this movie is utterly ludicrous, it is never boring, and its director stages its grotesqueries—a throat slashed here, a neck snapped there—with energy and wit. By the time a symbolic necklace makes a portentous reappearance, it is difficult not to smile at Soderbergh’s no-holds-barred approach.

Beyond its ability to regularly deliver brutish genre thrills, Unsane is most noteworthy as a star vehicle for Foy, whose lithe and vigorous performance may as well come with a sign that reads, “I am more than just the Queen in The Crown.” On that show, Foy excels at articulating inner anguish and desire, emotions that decorum prevents from bubbling to the surface. Sawyer is likewise incapacitated by circumstance—she too suffers at the hands of a rigid system that dehumanizes its members—but that’s pretty much where the similarities end. And while Foy occasionally struggles with her American accent, she plainly relishes the opportunity to externalize her rage. Sawyer is intelligent but impulsive, frightened but vicious, and Foy manages to garner your sympathies while also making you wonder if she just might be a lunatic. She’s playing Lisbeth Salander next, and while I’m wary of studios recycling that character, after Unsane, the idea that Foy can anchor a new cinematic franchise is far from crazy.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.