Action-packed but not kinetic, stimulating but not engaging, immersive but not intimate—Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here might be described as an anti-thriller. Its plot, which is essentially Taken by way of Taxi Driver, features a handful of genre staples: a rugged but troubled hero, a girl in peril, a cadre of reprehensible evildoers, crushed skulls and buckets of blood. But while the movie hits all of the familiar revenge-narrative beats, it does so in decidedly offbeat ways, preferring to linger in the unsettling spaces that bubble up between the requisite moments of violence and mayhem. It’s less interested in elevating your pulse than in digging under your skin.

This approach has its rewards. You will surely see more exciting movies in 2018 than You Were Never Really Here, but you may not see a more distinctive one, and there’s intrigue in the way Ramsay upends expectations and shows you something creepy and new. But her assaultive style has limitations, too; when viewed from a certain angle, her commitment to jaggedness is less suggestive of a disciplined artist abiding by her principles than of a smug director refusing to entertain her audience. The result is a film that’s easy to admire but difficult to, you know, actually like.

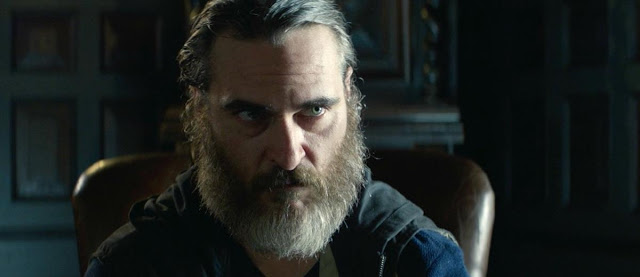

But let’s start with the positive. The most obvious target for your admiration is Joaquin Phoenix, that most dedicated of actors who burrows into his roles with disturbing intensity. A gift to any filmmaker, Phoenix’s ability to internalize anguish makes him a particularly good fit with Ramsay, who likes to turn her protagonists inside-out and upside-down. Her prior two features—Morvern Callar (starring Samantha Morton) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (Tilda Swinton)—explored women locked in perpetual struggle with themselves, and while Phoenix may carry a Y chromosome, he maintains that legacy of inner turmoil here. With burly arms and an even bigger belly, he lends his character—a mumbly, suicidal gun for hire called Joe, who’s both nominally and thematically related to the hulking antihero Nicolas Cage played in the 2014 movie that shares the character’s name—a bone-deep existential despair that seems to seep from his pores and gets matted in his thick, greying beard.

Phoenix’s crumbling humanity is something of an emotional life raft in a film that endeavors to drown you in pain, roughness, and confusion. To be fair, You Were Never Really Here wastes no time disguising its intentions or camouflaging its methods; it opens in a nondescript motel room where anonymous trinkets litter the floor and a man lies on the bed, his ragged breathing muffled by the plastic bag that he has inexplicably pressed over his face. That’s our Joe, and we learn as much about him in this grim introduction as we do over the next half hour, during which he pummels a random assailant in an alley, hops into a Cincinnati cab, makes an ominous phone call (“It’s done”), and returns to New York, where he cares for his frail mother (Judith Roberts). Adapting the novella by Jonathan Ames, Ramsay’s economical approach makes good sense; she’s a shower rather than a teller, and with Phoenix silently conveying Joe’s disillusionment, she doesn’t bother wasting time on getting-to-know-you dialogue or needless exposition.

Which doesn’t mean that she’s precise. To the contrary, Ramsay favors a disorienting technique that’s aggressively hyperactive in both sound and image. (Thriller connoisseurs may be reminded of Good Time, another messy Big Apple escapade that trafficked in human misery, though Ramsay is a more intelligent and less sloppy director than the Safdie brothers.) Throughout its brief runtime, You Were Never Really Here periodically erupts in sudden cutaways and bursts of random noise. Childish voices chatter nonsensically, often counting down from round numbers (30, 50, 10), while the music by Jonny Greenwood—returning to his discordant roots after delivering an atypically gorgeous score for Phantom Thread—clatters with woozy dissonance. Presumed flashbacks reveal fleeting glimpses of various terrors—a boy hiding under a table from an abusive father, a blinding foreign desert of military malfeasance, a storage container piled with lifeless bodies—without explanation or cogency. It’s visions of death by a thousand editing cuts.

The goal of all this quick-hitting agony, I suspect, is to pull you inside Joe’s fraying mind and expose you to his wounded soul. Mission accomplished, I suppose, but the sound execution of Ramsay’s process doesn’t necessarily equate to cinematic success. Watching this movie, I was always on edge, but I was rarely engrossed; Ramsay’s method, blanketing you as it does, can feel queasy and punishing. And where We Need to Talk About Kevin eventually sloughed off its jittery antics as it crescendoed to a climax of terrible clarity, You Were Never Really Here remains persistently off-putting.

Sometimes, though, it develops momentum in spite of itself. The plot—which follows Joe’s desperate attempts to rescue a preteen girl (Ekaterina Samsonov) from the clutches of some evil politicians who operate a grotesque sex ring—proceeds with the expected twists and turns, but Ramsay’s syncopated style acquires power when twinned with the story’s blunt-force brutality. It’s telling that most of the film’s violence—Joe is handy with a gun, but his weapon of choice is a ball-peen hammer—takes place either offscreen or from a distance, as during a riveting sequence where Joe storms a building and wreaks havoc; we watch all of the carnage on grainy security cameras, a remove that somehow intensifies the ferocity.

To borrow a line from another revenge thriller, death is Joe’s art, but it is also this movie’s primary preoccupation, which may be why Ramsay seems most invested after the bodies hit the floor. (She’s certainly more concerned with her characters’ mortality than with narrative plausibility.) As grimy and savage as You Were Never Really Here may be, it finds room for sporadic moments of startling gentleness. A sequence where Joe lays a loved one to rest in a lake is lovely in its quiet, shafts of light penetrating the water with messianic symbolism. And in the film’s most astonishing scene, after Joe fells a pair of would-be killers, one of them spends his death throes softly singing along to a ’70s ballad playing on the radio, before Joe joins him in a whispered, funereal duet. In moments such as these, You Were Never Really is weirdly, hauntingly beautiful.

Yet it is also ugly. Perhaps my tony tastes are simply too delicate for Ramsay’s bruising belligerence, but her relentless activity ultimately proves exhausting and enervating rather than invigorating. You Were Never Really Here is well worth seeing, both for Phoenix’s performance—he is always really good—and for the intellectual satisfaction of watching an artist apply her talents without quarter. But while I can appreciate the singularity of Ramsay’s vision, I’m not sure she needed to swing her avant-garde hammer quite so hard.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.