Did you know that technology is, like, A Thing? Were you aware that people regularly communicate via the internet, often in the guise of false personas? Have you ever grappled with the reality that innovations in hardware and software have, in both positive and negative ways, forever changed the contours of human interaction? If your answer to these questions is no, then you are sure to be electrified by Searching, a clever and gimmicky little thriller directed by Aneesh Chaganty. But if you have even the faintest familiarity with online culture—if you have a Gmail account or an iPhone or a web browser—you may find this film’s purported insights to be stale and preachy. Who knew the kids these days were so darned secretive?

I dare say most of us. But just as we shouldn’t judge an online account based on its avatar (whoops, spoiler alert!), we shouldn’t judge a movie for its tiresome themes alone. And Searching, despite its occasional shrillness, is a taut and engaging potboiler, as well as an audacious formal exercise. It may not have anything meaningful to say about technology, but it does use that technology in new and interesting ways.

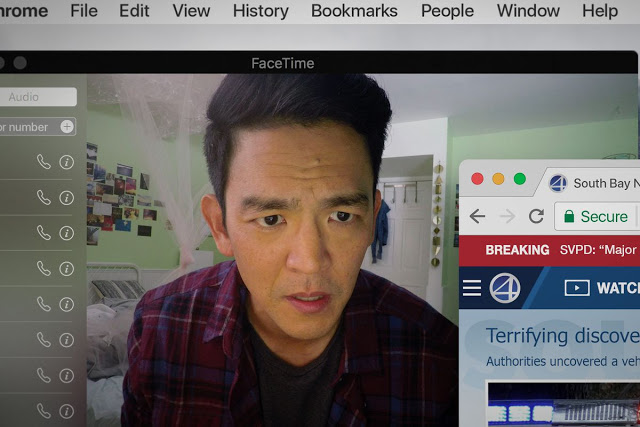

In a sense, Searching is the logical next step in an emerging subgenre of cinema that weaponizes scientific advancements against their users. Last decade witnessed the boom of found-footage horror, where in movies like Paranormal Activity and Cloverfield, digital cameras and smartphones shifted from devices of convenience to chroniclers of terror; recently, in the Unfriended films, the friendly confines of a group chat disintegrated into an arena of suspicion and murder. Searching is not strictly a horror film (though it certainly traffics in fear and desperation), but it nevertheless uses a similar grammar, as the entire movie appears to unfold on electronic screens—mostly the tiled windows of a desktop computer, plus the occasional cell phone.

Thematically, this is a dubious proposition. No doubt Chaganty wants his film to serve as a warning on the dangers of technology—the way it can cloak evil in anonymity even as it can also unite friends and families—but any force that his message carries becomes dulled through repetition and obviousness. Yet in terms of execution, Searching is something of a triumph. Rather than being hamstrung by his conceit, Chaganty maximizes its potential, thanks in part to its encyclopedic variety. The movie’s opening sequence alone, which tracks the upbringing of Margot (played as a 16-year-old by Michelle La) by her father David (John Cho) and late mother Pamela (Sara Sohn), is a marvel of precision and economy, condensing a decade and a half of life into a whirlwind compendium of emails, calendar appointments, and home videos. (It could form a formidable double feature with the title sequence of The Commuter.)

That opening dispenses a dizzying amount of information through a number of different means, but it never feels chaotic or disorienting. And perhaps the most impressive thing about Searching is not noticing how impressive it is. At times Chaganty appears to be compiling a Wikipedia entry on “Forms of modern communication”, ranging from the relatively prosaic (FaceTime, YouTube) to the social-media-focused (Facebook, Twitter) to the downright obscure (“What the hell is YouCast?”). But he’s done so with remarkable forethought, considering how to arrange this barrage of visual and textual data within the cinematic frame, and in frames within that frame; even simple tasks like minimizing a window elegantly lead into the next mode of electronic discovery. (Only during a few missed phone calls—those rarest of occasions where one person attempts to actually speak to another via airwaves—does Chaganty run into trouble, weirdly choosing to illustrate the process with threads of neon light pulsating against a dark background.) For all its conceptual bravura, Searching plays like a genuine movie; after awhile, you stop focusing on all the clicking and shuffling and toggling and just engage directly with the underlying story.

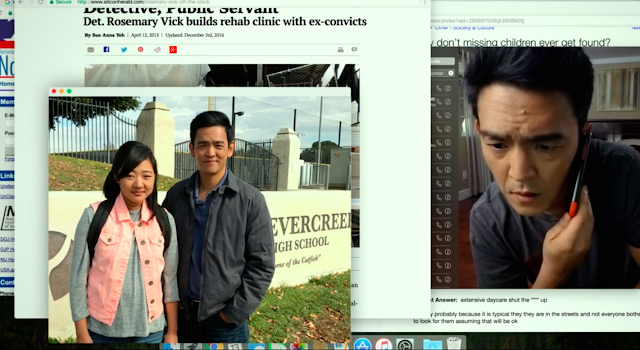

Which is, well, fine. The plot is splendidly simple: Margot disappears, and David naturally becomes obsessed with, ahem, looking for her. He receives the assistance of a sympathetic detective (Debra Messing), who still can’t stop him from conducting his own unsanctioned investigation, which involves everything from making spreadsheets to harassing Margot’s classmates online to beating up a punk at the local mall. The screenplay, by Chaganty and Sev Ohanian, is predictably unpredictable, suggesting a series of obvious suspects before revealing their innocence and moving on to the next target. Motives are debated, deceptions are uncovered, and seemingly innocuous words and images are revealed to be of major significance.

As a mystery thriller, Searching is perfectly adequate, which is another way of saying it’s disposable and unmemorable. But beyond its already-estimable technique, the movie has some things to say that, if not exactly profound, are at least worth reflecting on. One involves the concept of criminal crowdsourcing, the way cases can drastically mutate once they fall into the eager hands of the internet. As Margot’s disappearance gains notoriety, it becomes a cultural sensation as much as a missing-persons investigation, with the proliferation of hashtags that are both supportive (#FindMargot) and insidious (#DadDidIt). This isn’t exactly new territory, but the film at least exhibits a fluency in the wildfire nature of viral crimes and their incessant media coverage.

Beyond that, Searching ponders the eternal tension between parents and children, wondering if technology has allowed enterprising young people to more effectively hide their secret impulses and desires from their forebears. Again, this is hardly a revolutionary idea, but the movie manages to ground its sermonizing in human drama, thanks mostly to Cho’s steady, sympathetic performance. It’s been nearly two decades since the actor introduced us to the acronym “MILF” (related: I feel old), but he’s always demonstrated an everyman quality, even within the zaniness of the Harold and Kumar universe. David is a decent dad, which means he’s charmingly out of touch with his daughter (he doesn’t even know how to spell Tumblr, ha!), and Cho mingles feelings of shame and confusion along with the expected agony and indignation.

That those feelings aren’t diluted, even though we’re watching a screen within a screen, is a testament to Searching’s fluidity, as well as its conception of technology as a benevolent parasite that has infected even our most mundane social rituals. That the movie has been touted as Hitchcockian is absurd, but it’s also irrelevant; the real tension here lies not in the resolution of the mystery but in the inherent clumsiness of electronic interaction. Fearing that your daughter is dead? Sure, that’s excruciating. Sending an emotionally loaded text message, then seeing that dreaded ellipsis pop up and clutching your breath as the recipient begins to compose a reply? Now that’s suspense.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.