Describing Robert De Niro’s vicious mobster in Goodfellas, Ray Liotta says, “What he really loved to do was steal; I mean, he actually enjoyed it.” David Lowery’s The Old Man & the Gun also follows a real-life criminal with a genuine passion for robbery, but that’s pretty much where the similarities between the two films end. Never one to tackle genre material head-on—Ain’t Them Bodies Saints was ostensibly about lovers on a shooting spree, but it was really just a collage of pretty Texas pictures overlaid by Malickian voiceover—Lowery paints this story’s true-crime elements with a warm, humanist gloss. What would typically play as a gritty thriller—there’s even a cops-and-robbers angle, with an obsessed detective who makes it his mission to capture this audacious thief—instead unfolds as a leisurely character study of aging and contentment.

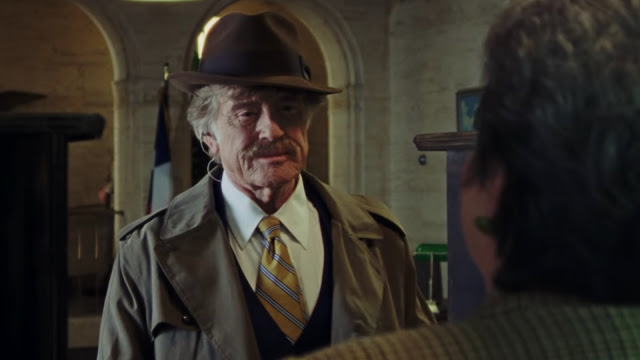

Mostly, The Old Man & the Gun is a showcase for Robert Redford, appearing in what is supposedly his final role. He plays Forrest Tucker, the felon who, as relayed in the David Grann article that formed the basis for Lowery’s screenplay, robbed nearly 100 banks over a 60-year span, escaping from prison more than a dozen times in the process. That’s quite the rap sheet, but Redford doesn’t exaggerate Tucker’s legend or puff up his stature. Instead, he delivers a sly and twinkly performance, investing this sundance elder with a strange integrity that’s part-pride, part-grace.

If The Old Man & the Gun is guilty of romanticizing the outlaw, that’s less a failure on Lowery’s part than a symptom of Forrest’s peculiar brand of criminal decency. For all the law-breaking that this movie depicts, there is very little sense of danger accompanying it. Everyone who meets Forrest, including his victims, finds him charming, not because he’s a daring scoundrel but because he’s a legitimately nice guy. “He was a perfect gentleman,” one ripped-off bank manager tells a dumbfounded detective. During another robbery, a young female teller begins to cry, only to compose herself when Forrest consoles her and insists that she’s doing a great job. Some people kill with kindness; Tucker steals with it.

He also steals the heart of Jewel (Sissy Spacek), a widow who owns a handsome ranch and who quickly falls under Forrest’s gentle spell. And in addition to operating as a sort of anti-thriller, The Old Man & the Gun plays as a tender golden-years romance. Where younger characters might find themselves tumbling into a torrid affair, Forrest and Jewel locate modest but sincere pleasure in each other’s company, sipping lemonade on a veranda and wistfully contemplating the long journeys they’ve both taken. Jewel, beyond acting as Forrest’s love interest, serves as an audience surrogate, mystified but nevertheless enchanted by this geezer’s likable lawlessness. On the opposite end of the spectrum, though no less decent a human being, is John Hunt (Casey Affleck), the Texas gumshoe who discovers a chain of robberies throughout the Southwest and eventually discerns that Forrest’s gang—which also includes a wheelman (Danny Glover) and a second (Tom Waits)—is the culprit. John, who is happily married with two children but seems to be stuck in a professional rut, becomes determined to put Tucker back behind bars, which in our eyes means he wants to spoil all the fun.

Like its subject, The Old Man & the Gun is persistently pleasant. And like its subject, its relentless amiability allows it to camouflage some of its failings, which rankle in retrospect. It’s one thing for Lowery to disdain cheap thrills as a matter of principle, but it’s quite another for Forrest’s actual heists to feel so half-formed, as though Lowery couldn’t be bothered to detail their mechanics. (An archetypal scene of Forrest and his cohorts performing reconnaissance seems to be arbitrarily inserted, given that it has no payoff whatsoever.) And a late plot development involving a betrayal is thinly sketched, suggestive of either lazy editing or blatant disregard for narrative coherence.

Of course, plot has never been of primary interest to Lowery, who prefers to make elliptical movies that focus on character and mood rather than story. In that context, The Old Man & the Gun is one of his more conventional films, especially when compared to his prior effort, A Ghost Story. That divisive picture, which starred Affleck as a silent apparition—and which was most memorable for its extraordinary scene of Rooney Mara gorging on a pie—was almost punishingly excellent; I wasn’t as enamored with it as many (it’s brutally slow in parts), but it was undeniably a major work, with bold and provocative ideas about cinematic aesthetics and storytelling. There’s only one sequence in The Old Man & the Gun that hints at that level of filmmaking verve: a late montage, set to music, depicting all of Forrest’s intrepid escapes. Otherwise, the film feels rather slight—a minor-key tune that’s designed to be cheerfully unmemorable.

Which is a compliment as well as a criticism. It takes real skill to craft something so sunnily appealing without coming across as timid. And while The Old Man & the Gun may lack vigor and excitement, there’s something authentic and enjoyable about its humility. At multiple points, the film recounts that whenever Forrest was apprehended by police in the midst of one of his thefts, he was smiling. For most of this agreeably forgettable movie, so was I.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.