Adam McKay fancies himself an educator. He may clothe his films in the garb of genre, but only as a way to stealthily impart some wisdom onto unsuspecting audiences. And so, The Other Guys was a dumb buddy-cop comedy that attempted to smuggle in some rhetoric about financial malfeasance; The Big Short more directly addressed the collapse of America’s housing market, but it did so in the guise of a playful procedural, chronicling how a few smart guys got rich while the banks went bankrupt. Now comes Vice, a cheerful comedy that also happens to be a biopic of one of the nation’s most loathsome politicians, Dick Cheney.

You may quarrel with McKay’s politics, but you cannot deny that as a director, he has developed his own signature style. That is not a compliment. Vice, which hectically barrels through four decades of Cheney’s life before slowing its pace slightly during his fateful years in the Bush administration, often seems like a two-hour music video—the ugliest, messiest, least sexy such video ever made. Each shaky shot is held for approximately two seconds, while every scene is constantly interrupted by a barrage of random inserts, whether quick-hitting flashbacks or footage of wildlife metaphorically moving in for the kill. It’s like if a history textbook were animated by Paul Greengrass.

McKay’s hyperactivity is so extreme, a few of his gimmicks are bound to hit their target. And so they do; as a movie, Vice may be disappointingly obtuse, but it features some very good and bleakly funny scenes. In one inspired sequence, Cheney and a handful of D.C. power brokers attend a fancy restaurant, where a waiter (Alfred Molina) offers a menu of the choicest options, only instead of dishes, they’re extralegal policies like “Rendition” and “Guantanamo Bay”. And maybe 45 minutes in, McKay pretends to end the movie, complete with a fake epilogue and closing-credits scroll. These moments of genuine wit tend to be offset by gambits that land with a thud—the scene where Cheney and his wife, Lynne (Amy Adams), suddenly start talking in Shakespearean verse is downright painful—but at least they keep things lively.

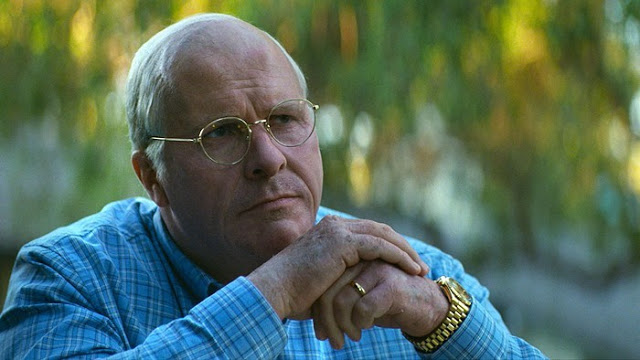

And even if you find McKay’s antics disorienting and nauseating, you are kept somewhat grounded by the impressive performances of his cast. Steve Carell plays Donald Rumsfeld as someone alarmingly fun to be around, while Sam Rockwell turns George W. Bush into a hopelessly pathetic patsy. Adams, of course, is razor-sharp as Lynne Cheney, portraying a woman who is decidedly intolerant of weakness. And then there is Christian Bale, delivering another of his inimitable acts of verbal and physical transformation. With a gravelly voice and a beach ball-sized belly, Bale’s Cheney is fundamentally unknowable, an enigma who strides through the halls of power with abject amorality, bending American policy to his own warped worldview.

Which is what, exactly? The message of Vice, beyond some boilerplate political wailing, seems to be that the only thing Dick Cheney believed in was Dick Cheney. That’s probably true, but it doesn’t make the man very interesting, either as a historical figure or a movie character. Bale’s performance is technically remarkable, but he and McKay fail to generate any real insight into their subject, which means they’re forced to fall back on a tiresome combination of mockery and disbelief. The film opens with some cutesy text noting that, because Cheney cloaked his life in secrecy, its fact-based narrative is only “as true as it can be”. That’s a clever bit of lampshading, but it really just acknowledges the movie’s essential emptiness. It may have taken a half-century before Cheney’s pattern of dissembling and deceiving was unmasked, but Vice is fraudulent from the get-go.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.