A punishing movie whose bits of greatness are obscured by a fog of auteurist pretension, The Lighthouse is a deeply frustrating experience, a tantalizing work that defies explanation and categorization. It defies enjoyment too; as technically impressive and formidably confident as it may be, it isn’t much fun to watch. But it does carry a genuine personality, the imprint of a director who refuses to sacrifice his bizarre vision for the sake of more quotidian values like accessibility. Or, you know, coherence.

That director is Robert Eggers, whose first feature, the terrific horror movie The Witch, blended creeptastic folk-story terror with silky filmmaking craft. It also featured characters speaking in period-specific dialect, a trick Eggers repeats here, though the setting has been bumped up by a few centuries to the late 1800s. The screenplay, which Eggers wrote with his brother Max, is laden with old-timey jargon—“aye” in place of “yes”, “ye” instead of “you”, etc.—which enhances the film’s already-ornate degree of detail. Assuming, of course, you can understand what the hell they’re saying.

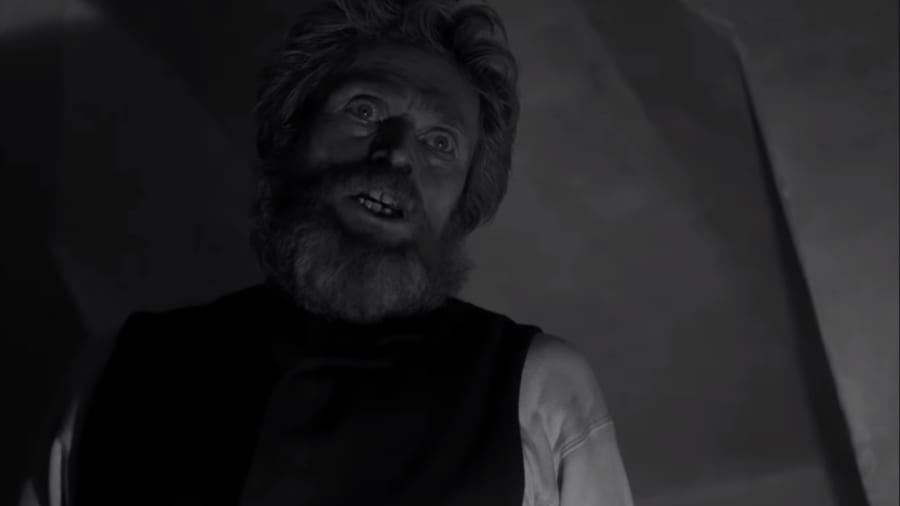

“You must have misheard,” the lighthouse keeper Thomas (a very fine Willem Dafoe) says at one point to his underling, Winslow (Robert Pattinson). If he did, he isn’t the only one. A claustrophobic two-hander of vigorous one-upmanship, The Lighthouse demands intense performances, and both of Eggers’ actors oblige, throwing themselves completely into their roles. (They’re also equipped with robust facial hair: Pattinson a heavy mustache, Dafoe a bushy beard that might as well be a bird’s nest.) Unfortunately, that commitment extends to their thick longshoreman accents, an inflection that results in consonants being swallowed like cold soup. Perhaps Eggers intended this unintelligibility to function on a metaphoric level, heightening the alien nature of the world that he has so scrupulously constructed. Regardless, you may find your hand instinctively reaching for a phantom remote control, hoping futilely that someone might turn on the subtitles.

Not that your comprehension of the language much matters. The Lighthouse is less about plot than about mood, attempting to suck you into its black hole of isolation and paranoia. It’s a story of what happens when two strong-willed men are forced to share close quarters for an extended period, with nothing but each other, alcohol, and the cruelties of nature for company. For reasons unknown (but which you’ll surely speculate on), Winslow accepts short-term employment as a “wickie”, otherwise known as an assistant to Thomas, the maritime veteran who masters a barren spit of land off the coast of Maine. Initially, Winslow assumes that they’ll divide the duties equally, but Thomas has other ideas—“The light is mine,” he declares, brooking no argument—leaving his minion to tend to the job’s less appealing aspects. The film’s opening act follows Winslow as he acclimates to his unforgiving new environment and performs tasks that are decidedly unglamorous: hammering shingles, cleaning cisterns, shoveling filth. When he empties a chamber pot into the sea, its contents get unceremoniously blown back into his face.

It’s hard, dirty work, but while The Lighthouse can be a very ugly movie—screen it in Smell-O-Vision, and it would surely reek of piss, shit, and farts—it’s also kind of beautiful. Shot in stark black-and-white and framed in a boxy aspect ratio, the film is spartan but textured, Eggers’ camera dispassionately capturing the coldness of the landscape. (As with The Witch, the cinematographer is Jarin Blaschke.) The sound design is impeccable; a foghorn is constantly heard blaring in the distance, a distant symbol of the vestiges of society. One of the people thanked in the closing credits is Ari Aster, and while this critic may prefer that director’s supple maximalism, Eggers plainly shares with him the conviction that even the most brutal of stories should be told with painstaking craft. (A double feature of this film and The Light Between Oceans, Derek Cianfrance’s elegant and aggressively gentle melodrama, would result in quite the case of tonal whiplash.)

Eggers’ technique may be striking, but it doesn’t render The Lighthouse especially entertaining. The movie’s first half, which (to the extent it focuses on anything) centers on the fraught and wary bond that develops between Winslow and Thomas, is dreary and unpleasant. There are unexplained phenomena of varying degrees of inexplicability: a naked man caught in a trance; a seagull with an apparent vendetta; a venomous mermaid that washes ashore. It’s both tedious and silly, an eye-catching collage of eerie nonsense.

Winslow begins the proceedings sober, but once he falls off the wagon at the rough halfway point, the film picks up in energy, if not in logic. Again, this is presumably by design; The Lighthouse is a movie about men caught in the grips of madness, and Eggers seeks to pull us inside his characters’ diseased minds. But even as the film acquires a bit of narrative momentum and indulges in some well-executed genre thrills—bloodstained axes, heedless brawls, ghastly burials—its effect is distancing rather than immersive. Perhaps Eggers is a victim of his own success (imagine what insanity feels like!), or perhaps he simply fails to tether his outré flourishes to a recognizable human element; either way, despite badly craving to do so, he never satisfactorily articulates a suffocating sense of sickly desperation.

Despite these faults, The Lighthouse is not without its fearsome pleasures, chief among them its lead performances. Pattinson effectively communicates Winslow’s mounting misery and frustration, culminating in a juicy, hilarious monologue where he savagely insults Thomas’ stink, comparing it to—among other things—“curdled foreskin”. (A separate scene, in which he announces his desire to copulate with a steak, is destined to be preserved in a thousand memes; compared to Winslow, the despondent astronaut whom Pattinson played in High Life seems positively suave, though both masturbate quite a bit.) It’s Dafoe, however, who really shines. He has his own meaty speeches, and he tears into Eggers’ flavorful dialogue with evident relish, but he also locates a tendril of grief amid the absurdity. To the extent the movie is memorable for reasons beyond its own strangeness, it’s thanks to the hidden grace notes of Dafoe’s sly performance.

Defiantly abstruse to the very end, The Lighthouse envelops itself in an enigmatic haziness that invites basic questions and promotes wild conjecture. Where exactly are Winslow and Thomas? When are they? Are they in purgatory? Is it all a dream? Eggers, of course, has no interest in resolving these conundrums; to the contrary, he lampshades them, with Thomas at one point suggesting that he just might be a figment of Winslow’s imagination.

It makes no difference, of course. The harsh joke of The Lighthouse is that the truth of its narrative is irrelevant; all that matters is the experience, the sensation, the mystery. It’s a clever enough idea, but it proves diminishing, exposing the emptiness at the movie’s core. In the end, that titular structure—which extends straight into the night sky like a beacon of civilization, or maybe just a trolling middle finger—is something of a symbolic feint; there are no guideposts here, nothing to rescue you from the crashing waves of lunacy that Eggers has so vividly created. That may qualify as an achievement, but it also reveals that in this grimy universe, meaning—and enjoyment—are hard to find.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.