Success stories can’t be simple. Presumably, many gifted artists and athletes achieve their goals through little more than the straightforward combination of labor and talent, without facing any daunting challenges or making any personal sacrifices. But who wants to watch a movie about them? Drama requires conflict, which is why rousing tales of ultimate success must contain moments of intervening failure. (Pictures about sustained failure are far more rare, give or take an Inside Llewyn Davis.) Last week featured the premiere of two fact-based films about obsessive geniuses: Warner Brothers’ King Richard, about the father of Venus and Serena Williams, and Netflix’s Tick, Tick… Boom, about the early struggles of the creator of Rent. One teeters perilously on the border of hagiography, while the other is largely enjoyable on its own artistic terms, but both are steeped in the cinematic wellspring of toil, triumph, anguish, and redemption.

Technically, King Richard isn’t so much the story of a genius as that of the man behind the genius(es), though I’m sure if you posed that framing to Richard Williams, he’d dismiss the distinction as one without a difference. Whether this on-screen version of Richard, incarnated by Will Smith with twinkly charm and bottomless gumption, represents a drastic departure from the actual man is a debate best left to historians and biographers. What matters here is whether this Richard is the suitable protagonist of a predictable, rags-to-riches sports picture—whether he is sufficiently separable from the countless coaches and motivators who have preceded him in the illustrious screen tradition of drilling, aggravating, and speechifying.

And there are moments in King Richard when the creative team—which comprises director Reinaldo Marcus Green, writer Zach Baylin, and of course Smith himself—delivers a character who’s worthy of headlining his own movie. Despite its title, the screenplay isn’t so much interested in depicting Richard’s tyrannical training tactics—for the most part, his daughters (played by Saniyya Sidney and Demi Singleton) adore and respect him—as in exploring his efforts to break into an exclusive citadel whose fortifications have heretofore walled off poor, Black members. In his edgy encounters with prospective coaches and agents, the Richard we meet is simultaneously ingratiating and inflexible, a sycophant and a shit-stirrer. “We appreciate everybody taking off their hoods before we came in,” he says with a broad smile at a country club, transforming an enthusiastic pitch meeting into a session of clenched awkwardness. (His ultimate response to the entreaties of an upper-crust manager, portrayed by a cigar-chomping Dylan McDermott, is a gloriously impolite fart.) And even when he successfully retains the services of qualified coaches—first played by Tony Goldwyn, then a wonderful (and wonderfully mustachioed) Jon Bernthal—he constantly undermines them, whether by questioning their technique or sabotaging their plans.

Smith is brilliant in these sequences, spiking his innate likability with large helpings of bold, distasteful arrogance. Yet Richard’s feverish exploitation of his daughters isn’t entirely mercenary. He is deeply committed to (and convinced of) their future stardom, but he also insists that they receive an education, and he even removes them from playing junior-circuit tournaments, an unprecedented maneuver for aspiring tennis pros. These contradictions gesture toward a legitimately complex character, one whose virtues and flaws mingle in peculiar ways; they also leave him ripe for the scathing excoriation he receives at the hands of his wife (Aunjanue Ellis), who upbraids him for his overbearing self-righteousness.

It’s a shame, then, that King Richard eventually reveals itself as a thoroughly conventional sports movie, with the standard big sermons, big doubts, and big game. Green, whose first feature was the intriguing melodrama Monsters and Men, stages the tennis sequences competently enough, and despite the obligatory ESPN inserts, he thankfully keeps the explanatory commentating to a minimum. At the same time, he lacks discipline in the editing room; the climactic match between Venus and Arantxa Sanchez Vicario goes on for ages, further padding out a film that runs a sometimes-oppressive 145 minutes.

Nor are King Richard’s clichés limited to its final act. An early subplot, in which Richard tries to avoid the gang violence that plagues Compton, concludes with a risible drive-by execution (call it a slay-us ex machina) that spares him from himself. Green and Baylin also decline to treat Venus and Serena as actual characters, instead painting them as sympathetic avatars of athletic excellence, and providing clumsily literal confirmations of their greatness. (The real-life sisters served as executive producers.) Serena Williams is arguably the best tennis player of all time, and if you didn’t know that before watching this movie, you sure do after—not only because of the compulsory closing text describing her accomplishments, but because the script includes a scene in which Richard prophesies that she will become the greatest of all time.

King Richard, of course, is about Richard, not his daughters. Yet despite some flashes of provocation, Smith and Green ultimately shrink from the challenge of illuminating Richard Williams as a knotty patriarch, instead sanding him down and treating him as the fulcrum for boilerplate biopic sap. Again, the problem isn’t one of historical inaccuracy but dramatic laziness. As Richard grows increasingly wise and perceptive—finding common ground with Bernthal’s earnest coach, outmaneuvering a Nike executive on a potential endorsement deal, calmly preaching patience and persistence—he becomes progressively less interesting. Tennis, for all of its straight lines and boxy dimensions, is a game of infinite shots and spins. But over time, King Richard instead imitates the ball machine that the girls train on: consistently producing material right down the middle, at regular intervals, without variation or surprise.

In some ways, the storytelling rhythms of Tick, Tick… Boom! are even more familiar than those of King Richard. The directorial debut of Lin-Manuel Miranda from a script by Steven Levenson, it centers on a recognizably tortured genius, the playwright Jonathan Larson (a splendid Andrew Garfield), whose strenuous passion for his art is revealed to be both admirable and alienating. Conceptually, Tick Tick Boom (you’ll forgive me for dropping the cumbersome punctuation going forward) is something of a figure-eight, navigating both past and future at once: It’s an adaptation of Larson’s modest 1992 one-man show of the same title, which relays the saga of his extensive failed efforts to produce his first play—a terrible-sounding science-fiction musical epic called Superbia—but it’s also informed by Larson’s subsequent (and posthumous) rise to stardom, after he wrote a little show called Rent.

It doesn’t require a Ph.D in rocket science (or musical theater) to discern what attracted Miranda to Larson’s output. Yet while Tick Tick Boom is littered with allusions, homages, and cameos—a veritable paradise of theater-kid pandering—it also largely works as a robust, faintly traditional movie musical. Miranda doesn’t quite demonstrate the exotic visual imagination that Jon M. Chu flaunted in the big-screen adaptation of Miranda’s own In the Heights, but he nonetheless proves himself a capable choreographer of song and dance.

Whether he can bring nuance to a somewhat tedious plot is another matter. The brunt of Tick Tick Boom takes place on the eve of Jonathan’s 30th birthday, as he panics over the impending workshop of Superbia—wrangling aloof agents, tentative actors, and pesky bill collectors. Jonathan’s existential crisis—the gnawing fear that he isn’t cut out for Broadway, and that he might need to relinquish his lifelong dream of becoming the next Sondheim (who appears, for a handful of scenes, in the rueful guise of Bradley Whitford) in favor of getting a real job—isn’t exactly fresh; a scene where he participates in a focus group and contemplates a soulless future in corporate advertising is overly glib, and much of the film’s dramatic material feels either slight or contrived. This is especially true of his relationship with Susan (Alexandra Shipp), his supportive and solicitous girlfriend who has conveniently just nabbed a teaching position in the Berkshires that comes with a Damoclean deadline. “You’re the artist, I’m the girlfriend,” Susan claims, a stinging rebuke of Jonathan’s priorities that also doubles as an accurate critique of the movie’s secondary characters.

That said, there’s a certain honesty in Jonathan’s selfishness, and in Garfield’s rich, sweaty performance. He isn’t much of a singer, but he lends the character a kind of toxic decency; Jonathan is sweet, smart, sensitive, and a pretty lousy friend. The price of greatness, the movie seems to argue (if perhaps inadvertently), is the endemic neglect of wholesome and nurturing relationships, and Garfield conjures Jonathan as a creature of sincere obsessiveness—a purity of purpose that’s both extraordinary and unhealthy.

But about that singing: Jonathan promotes Superbia as “the first musical for the MTV generation”, and there’s something vaguely music-video-ish about Miranda’s staging, especially early on; the opening number, “30/90,” betrays a lackadaisical focus, with the camera flitting to various performers belting out their notes without any discernible discipline. Miranda is also necessarily hamstrung by Larson’s lyrics, which are more functional than memorable. One of the film’s subplots involves Jonathan’s yearslong quest to compose a cathartic ballad, but the end result—the pleasant but forgettable “Come to Your Senses”—lacks the oomph mandated by the buildup.

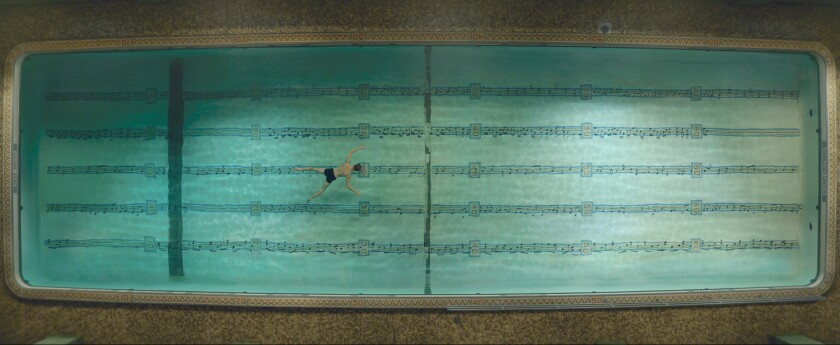

Still, Tick Tick Boom packs plenty of volume into its two hours, and as it progresses, Miranda’s technique grows bolder and livelier. The most inventive song is “Therapy”, in which Jonathan and a fellow collaborator (a vivacious Vanessa Hudgens) act out a sweltering fight between him and Susan in the plasticky manner of ventriloquist dummies. That level of productive stasis turns into dynamic motion in “No More”, in which Jonathan and his former roommate (Robin de Jesús) boast about fleeing the confines of their cramped studio for a swanky new high-rise; it also wraps with a very funny smash cut from elevator to subway. (Also moderately funny: As Jonathan glumly limps through the theater district, we see posters advertising upcoming shows with satirical titles like “White People Arguing About Marriage,” “Old Songs You Already Like,” and “Shakespeare: Does It Even Matter Which One?”) And if “Swimming” propagates the pernicious myth that great art can be composed through a blast of eureka inspiration, it at least provides the lovely image of a pool floor transforming into a ribbon of sheet music.

If Tick Tick Boom rarely operates as anything beyond a pleasing array of musical numbers (plus a showcase for Garfield), it’s plenty charming on those terms alone. To the extent it resonates further, it’s thanks to its period setting; the movie takes place in 1990, when the AIDS epidemic was ravaging pockets of the country. That may make the film sound dated or preachy, but as America finds itself gripped by yet another perversely politicized public-health crisis, it’s worth remembering how fearmongering and bigotry can carry the cost of human lives.

Larson capitalized on that idea with Rent, but the set piece in Tick Tick Boom which reverberates loudest lies a world apart from real-world notions of turmoil or loss. It is instead “Sunday”, a gentle fantasy sequence inspired by Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George in which Jonathan—who has previously worried that he’s becoming “a waiter with a hobby”—imagines the walls of the diner he works at melting away, as he conducts a choir composed of Broadway luminaries. It’s utterly shameless, an obvious excuse for Miranda to recruit all of his buddies and idols—look, there’s Renée Elise Goldsberry and Phillipa Soo from Hamilton! there’s Bebe Neuwirth and Bernadette Peters, they both won Tonys!—but it’s also a jubilant piece of daydreaming. Art’s function, it reminds us, isn’t always to reflect ugliness and truth. Sometimes, before the harsh clock of reality strikes, a genius needs to give us an escape.

King Richard grade: B-

Tick Tick Boom grade: B

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.