The title of Beau Is Afraid may be a declarative statement, but its contents prompt an earnest question: Can you blame him? The story of a man beset by all manner of physical and existential terrors—angry neighbors, poisonous insects, deranged combat veterans, despondent cheerleaders, mommy issues, and (above all) his own crippling anxiety—Ari Aster’s third feature is a cavalcade of fear and anguish. Such torment is perhaps to be expected from the dude who became an indie-horror sensation with Hereditary; what’s surprising about Beau Is Afraid is that it’s such a rollicking entertainment. Sure, it subjects its hero to an unceasing ordeal of misery and humiliation, but it does so in a way that’s often (if not always) hypnotic, beautiful, and funny.

None of those adjectives would apply to Beau himself; in fact, his personality seems to revolve around a single emotion, and it’s right there in the title. We first meet Beau when he first meets the world: The film’s opening scene (“impression” might be a more accurate word) simulates the process of his birth—an unnerving disharmony of yelps and screams, set against an inky blackness that gradually gives way to blinding light. It’s one of the only times in the movie when Aster wields his formidable talent with visible stress, and it’s a bold introduction to a picture that is at once rigorous and chaotic.

The sheer ambition of Beau Is Afraid—it runs three hours, conjures glorious and ghoulish images, and tells a sprawling tale that makes very little sense—risks obscuring the meticulousness of Aster’s craft. As a writer, he tends to be impish and perverse, layering his script with enigmatic flourishes and cheeky easter eggs. (Among the signposts littering the background is a placard that reads, “Death by anal, murder by fuck,” a warning which carries greater plot significance than you might expect.) As a director, however, he is a resolute formalist. His latest film may be a bizarre phantasmagorical journey inside the recesses of its protagonist’s fraying mind, but its aesthetic is one of polish and precision. Robert Eggers, the peer Aster is often compared to, pulled off a similar trick with The Northman, but where that Norse epic was grandly melodramatic, Beau Is Afraid is discordant and elusive.

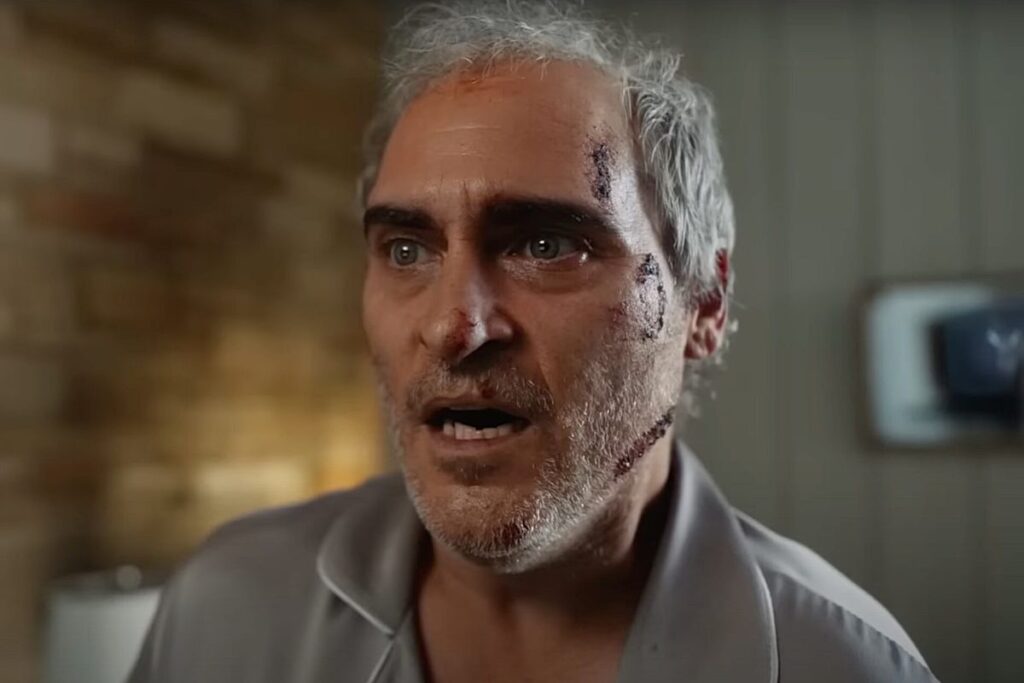

Tonally and structurally, the movie carries a mythological component, following its hero’s arduous attempts to complete a fairly straightforward quest. Beau, who is portrayed with abiding honesty by Joaquin Phoenix (in flashbacks, a bright-eyed Armen Nahapetian plays him as a teenager), wants to return home to visit his mother. Well, whether he wants to is a matter of perspective—pressing him on his attitude toward his maternal relationship, his therapist (Stephen McKinley Henderson) scrawls the word “guilty” across his notepad—but he’s supposed to. This requires him to travel from his grubby apartment—located in an unnamed metropolis (filming took place in Montreal) that seethes with anger, anarchy, and brutality—to catch a flight at the airport. Executing such a simple task proves more complicated than he might have hoped.

The opening passages of Beau Is Afraid are exhilarating in their finely wrought mayhem and swelling panic. Aster takes seemingly mundane incidents—a lost set of keys, a carelessly swallowed pill, a clogged faucet—and stacks them on top of each other (and on top of Beau) such that they amass the weight of an anvil. The sequence in which a frantic Beau attempts to buy a bottle of water from a convenience store is masterfully conceived and shot, with Aster using brilliant depth of field to depict Beau’s once-solitary residence turning into a haven for junkies, vagrants, and nymphomaniacs. The scenes that follow—a hilariously strained phone call with a UPS deliveryman who has discovered some dreadful news; a cleansing bath that morphs into an unexpected confrontation with an apologetic intruder and a remorseless spider—are equally transfixing, accumulating a delicious blend of intensity, agony, and comedy.

It’s unclear whether Aster could have maintained this level of berserk helplessness for the entirety of Beau Is Afraid’s extravagant runtime, because he doesn’t really try to. Instead, he subjects Beau to an arc of Odyssean episodes whose degree of mania naturally ebbs and flows. The movie’s quality follows a similar pattern, as some of Beau’s travails are more arresting than others. The high point—an animated interlude in which he inexplicably becomes a character within a wandering troupe’s whimsical play—is rapturously imaginative, and it confirms Aster’s gift for infusing narrative oddity with painterly beauty. Later, Beau’s reunion with an old would-be flame (Parker Posey, very fine) contemplates a different sort of ecstasy, and the fruits of their coupling are both suspenseful and hysterical. His time spent in the company of a wealthy family—the eager parents are played with brio by Nathan Lane and Amy Ryan, while the promising Kylie Rogers portrays their unhinged, pill-popping teenage daughter—is more uneven; ingenious bits (a curiously monogrammed robe, a glimpse of time-traveling surveillance footage) jostle uneasily alongside more aimless sequences, as when the daughter and her smiling friend chauffeur Beau around (and get him high) for no apparent reason. And a climactic scene set in an attic is too grotesque for me to bear, especially for the way it puts the “ick” in testicular.

Presumably, the thematic thread meant to connect these disparate strands of madness is our main character’s omnipresent fear. Yet while Beau has ample reason to be afraid—of meds, of thugs, of sex, of death, of Oedipal prophecies (Patti LuPone chews scenery as his mother)—I’m not convinced that Aster has much interesting to say about anxiety. In a sense, the movie is a victim of its own artistry; it is too distinctive, too singular, to function as a meaningful metaphor. (The obvious comparisons to the oeuvre of Charlie Kaufman aren’t always flattering, though the denouement set in a maritime amphitheater—recalling the yawning gallery of Synecdoche, New York—scores points for its striking production design.) It is certainly alarming to learn that a shattered chandelier now lies in the place where your mom’s head used to be, but it isn’t exactly thought-provoking.

What does unify Beau Is Afraid—what brings shape and consistency to its jagged shards of invention—is Phoenix. The unnervingly dedicated actor again transforms his body (remember that skeletal creep from Joker? Now he’s a doughy schlub with man-boobs), but his commitment to the role is more than just physical. Beau’s escalating predicament may play as blackly comic, but Phoenix refuses to wink at the absurdity; instead, he plays it straight, with a reactive terror that’s both deeply convincing and strangely sincere. In so doing, he reins in his director’s mischievousness, grounding the movie’s fanciful lunacies in real human emotion.

And as arch and playful as Beau Is Afraid may be, it nonetheless feels like a genuine piece of true creativity. Aster’s latest leviathan is in some ways his most remote work, lacking the pervasive dread of Hereditary or the ravishing grief of Midsommar. (The latter, for this critic’s money, remains his finest combination of outré danger and supple technique.) But it is also the product of an artist who refuses to repeat himself, and who continues to channel his virtuosic skill in exciting new ways. That aforementioned play-within-a-play sequence is breathtaking not just because it transports Beau into a fabricated cosmos (what’s real? who cares?), but because it unfolds with such powerful confidence and formal command. It’s a vigorous rejoinder to the constant doomsaying about the impending demise of cinema—a reminder that, for those viewers who thirst for intriguing and intoxicating new movies, there’s nothing to fear.

Grade: B+

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.