Late at night in a Manhattan bar, we see three people: an Asian woman seated in between two men (one white, the other Asian). They’re chatting amiably, but we can’t hear what they’re saying; instead, we listen to the observations of an unseen couple who speculate about the triad’s possible relationships. Perhaps two of them are married and the other man is her brother, they suggest, or maybe the white guy is an American tour guide. As they conjecture, the woman turns her head and looks directly into the camera, her eyes both inviting and comprehending of our attentions, as though she’s slyly caught us in the act.

This is the opening scene of Past Lives, the debut feature of writer-director Celine Song, and it immediately signals the film’s rare, delicate intimacy. When you buy a ticket for Past Lives, you end up not so much watching a movie as participating in an act of eavesdropping. Sure, you’re seeing actors pantomime a fictional story of love and loss, but you are also receiving an unauthorized glimpse into the inner worlds of two people—a secret chance to understand their desires and bear witness to their heartbreak.

The elegant force of Song’s construction isn’t immediately apparent. She builds the movie like a pyramid, setting a sturdy base before systematically loading it with increased weight and intensity. In the process, she wields her technique with invisible precision; there is nothing showy about her long takes or her steady framing (the cinematographer is Shabier Kirchner), but her fluidity makes the picture even more stealthily absorbing. Without rattling your senses or manipulating your emotions, she draws you in.

Aside from that tantalizing opening sequence (which functions as a flash-forward), the structure of Past Lives is rigorously linear. In a way, it operates as a compressed version of Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy: It contemplates the fulsome trajectory of a complex relationship via three discrete snapshots in time, each spaced 12 years apart. The first takes place in Seoul, where two schoolchildren—her name is Na Young (Moon Seung-ah), his is Hae Sung (Seung Min Yim)—find themselves straddling the distinctly pubescent boundary between friendship and flirtation. (Asked by her mother which boy she likes, Na Young identifies Hae Sung and describes him as “manly.”) Are they destined to be together? Fate would seem to have other plans, as Na Young’s family uproots to New York, severing this nascent connection before it can ever bloom.

And yet, the embers of their ineffable flame are not entirely extinguished. In the movie’s second chapter—which finds Na Young, having previously changed her name to Nora (Greta Lee), pursuing a career as a novelist, while Hae Sung (now played by Teo Yoo) completes his required military service—they reconnect via Facebook, leading to a series of Zoom calls that are charged with chemistry, frivolity, and a tinge of annoyance. “I’m supposed to be prepping for a workshop, and instead I’m researching flights to Seoul,” Nora complains during one of their lengthy chats. Her irritation is directed not just at the logistical challenges of maintaining an intercontinental friendship (the day-for-night time difference, the internet-plagued screen freezes), but also toward the instability that Hae Sung’s reemergence represents. She’s built a whole new life for herself in America; should she really risk sabotaging it in order to spend time with a guy she hasn’t talked to in a dozen years?

This is not necessarily a rhetorical question so much as one meant to underscore the film’s sizeable (if personal) dramatic stakes. For all its tenderness and tranquility, Past Lives functions as a fraught, nigh-violent collision between fantasy and reality. It carries the sweep and shape of a storybook romance—of a love that endures throughout decades and across oceans. It is also a work of unyielding honesty, reflecting soberly and sincerely on the implausibility of such histrionic tropes. The marvel of Song’s screenplay is that it treats this duality not as a conflict, but as complementary pieces of a consistent whole. Within her characters—and, one might argue, inside all of us—the majesty of art and the mundanity of life sit side by side.

The movie’s title derives from the Korean concept of in-yun: the idea that people who are connected in the present have repeatedly met as different incarnations in the past. It’s a provocative conceit, one that toys with philosophical notions of predestination, free will, and blind luck. It is also, in Nora’s hands, a comic punch line—a silly piece of folklore that Koreans “say to seduce someone.”

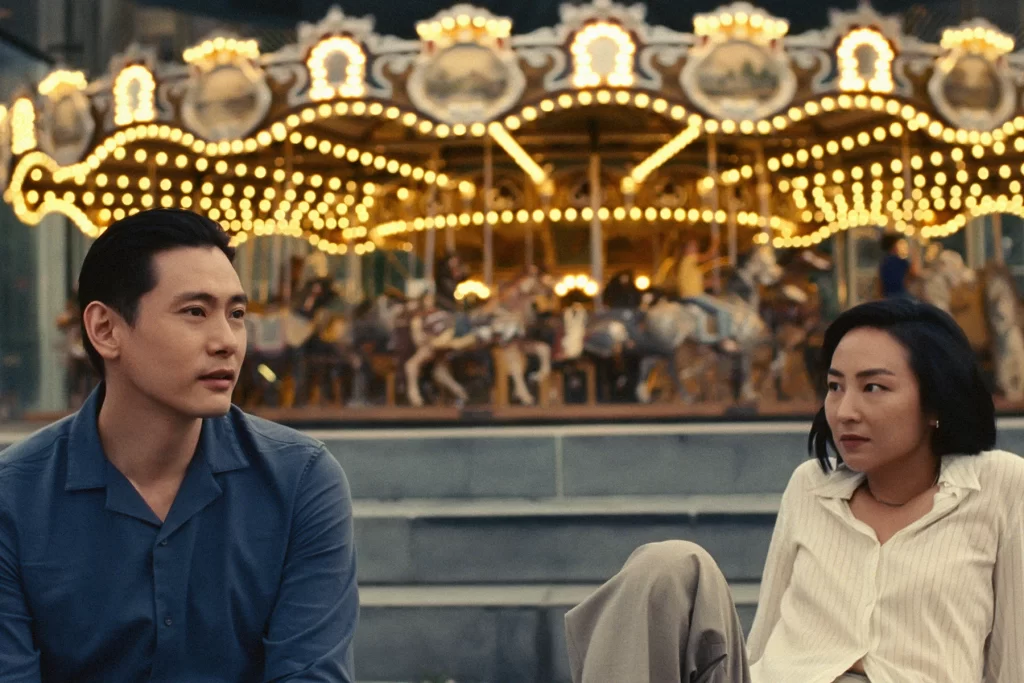

The target of Nora’s seduction, and the third person who rounds out Past Lives’ richly textured ensemble, is Arthur (John Magaro), a fellow writer who eventually becomes her husband. In the movie’s fabulously romantic and utterly devastating final act, which finds Hae Sung at long last visiting Nora on American soil, Arthur’s presence looms as a potential complication—a role he is well aware of. “I could be the villain of your story,” he acknowledges to Nora during a nocturnal chat that ripples with fear and poignancy. He’s not wrong. Yet he is also the keystone to unlocking the film’s limitless reserves of empathy. That Arthur is decidedly not a villain—that he instead wrestles compassionately with the fact of his wife’s enigmatic feelings for another man—is a testament to the generosity of Song’s characterizations and the lucidity of her insights.

It’s tempting to label Past Lives “talky,” given that it’s mostly composed of dialogue scenes. But while Song and her actors display a deft hand in exhibiting relaxed conversational rhythms, the key behavioral action on display is not speech but silence. There are numerous sequences of the characters simply looking at one another, their eyes conveying what their mouths cannot. This is a tricky thing for cinema to articulate, but Yoo, Magaro, and especially Lee all rise to the challenge with aplomb, their faces simultaneously concealing and communicating their feelings. The result is a picture of beautiful simplicity that is in no way simple.

Nobody ever shouts in Past Lives, and hardly anyone ever cries. Yet with quiet, persistent power, the movie accumulates a torrent of emotions, washing over you with its longing, its discernment, its humanity. When those tears finally do arrive, yours will surely be among them, and that’s only right. After all, just like that unnamed couple in the bar, you’re a part of this story too.

Grade: A

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.