Multiple times in It Ends with Us, the camera focuses on a crinkly napkin on which Lily Bloom (Blake Lively) has scrawled the numbers one through five in sequence. Lily’s mother (Amy Morton) has tasked her with delivering her father’s eulogy and has advised her to “just say your five favorite things about him,” but because Lily remembers her departed dad less than dearly, the rest of the wrinkled cotton remains blank. Yet when she stands at the funeral podium, Lily still retrieves the napkin from her pocket and glances at it—despite knowing full well that it contains no substantive text—before silently exiting the church.

This is not, strictly speaking, plausible behavior. But it nevertheless serves a purpose, loudly announcing the extent to which Lilly’s daddy issues have paralyzed her. And writ large, It Ends with Us proceeds accordingly to a similar pattern, sacrificing textural realism in the name of dramatic force. As a piece of storytelling, it is often clumsy and unpersuasive. As a work of messaging, it is engaging and even provocative.

Despite its somber gravity, It Ends with Us spends a healthy chunk of its runtime operating in the guise of a crowd-pleasing romantic comedy. Working from a screenplay by Christy Hall (adapting Colleen Hoover’s bestselling novel), director Justin Baldoni (Jane the Virgin) casts himself as Ryle (everyone in this movie has a stupid name), a tall, dark, and handsome stranger who also happens to be a neurosurgeon. He and Lily meet cute one evening on the roof of his apartment building—exactly what she’s doing up there is unclear, though her precarious position on the ledge implies suicidal ideation—and they quickly exhibit the kind of flirty, magnetizing chemistry often found in swoony cinema. When Lily asks Ryle to say something shocking, he instinctively replies, “I want to have sex with you.” Talk about a smooth operator!

Lily and Ryle don’t do the deed that night, instead sharing one of those long, heady kisses that’s conveniently interrupted by a ringing cell phone. But after Lily fulfills her lifelong dream of opening a flower shop and happens to hire Ryle’s sister, Allysa (Jenny Slate), as her first employee, Ryle reenters her orbit and reignites their mutual attraction. When they see each other at Allysa’s birthday party, with Lily wearing a sleek black number that seems to redefine the geometry of the dress, they tumble into bed together; when she slams the brakes on, he immediately declares that he’s going to sleep, a pivot designed to indicate that this smart and wealthy hunk is also the perfect gentleman. What could go wrong?

We’ll get to that. Initially, there’s a slickness to Lily and Ryle’s courtship that, while pleasant—it’s always nourishing to watch good-looking people realize they’re attracted to one another—is also somewhat artificial, suggesting a pantomime of passion. Perhaps recognizing this, the screenplay periodically flashes back to Lily’s teenage years, when she’s appealingly played by newcomer Isabela Ferrer and when she strikes up a tentative, freighted relationship with Atlas (American Rust’s Alex Neustaedter), a troubled youth who’s taken up residence in the boarded-up tenement that’s expediently located within sight of her pastoral backyard. These tender scenes (bonus points for showing teenagers using condoms), which initially seem digressive, lay the groundwork for a potential future love triangle—we are destined to meet Atlas as an adult, when he runs a well-regarded restaurant and is played by an unsmiling Brandon Sklenar—even as they also convey the breadth of the story’s ambitions and the cyclical nature of its themes.

About which: Despite its well-sculpted bodies and its breathy soundtrack (which includes both Lana Del Rey and Taylor Swift, plus Birdy’s cover of Bon Iver’s “Skinny Love”), It Ends with Us is not a sweeping love saga. Instead, at its rough halfway point, it transitions into a fraught portrait of domestic abuse. Ryle, for all his charming insouciance, is also a hot-tempered animal, prone to spasms of sudden, terrifying anger. The movie’s tonal arc gradually bends away from the joys of romantic connection and toward the ravages of spousal violence—first slowly revealing the depths of Ryle’s pathology, then contemplating Lily’s attempt to reclaim her agency.

This is very serious material, and Baldoni, as both director and actor, treats it with appropriate solemnity. But perhaps feeling beholden to Hoover’s book (which I have not read), he struggles to arrange the script’s textual arguments into a convincing picture. To begin with, Atlas is more of a construct than a character—a theoretical counterpoint who exists simply to activate Ryle’s rage and to serve as a safe harbor of male decency. (The film’s final scene is faintly appalling in this regard, though excising the tacky epilogue presumably would have infuriated Hoover’s loyal readers.)

Beyond that, It Ends with Us is so committed to advancing its noble ideas that it fails to exhibit any real detail or interiority. The movie is nominally set in Boston (filming took place in New Jersey), yet aside from the occasional Red Sox cap or Bruins reference, it contains no semblance of local color. (It has the misfortune of being released the same weekend as The Instigators, which is possibly the most Bostonian picture ever made.) As if worried you’ll be skeptical of Ryle’s work prowess, the screenplay constantly reminds you that he’s a neurosurgeon, mostly in the form of awkward lines like “How was your surgery?” and “Oh no, your surgery!” And despite Slate’s perky screen presence, Allysa is as flat a figure as Atlas; the cheerful scene where she requests a job at Lily’s shop is the rare capitalistic negotiation that doesn’t trouble itself with such trivial matters as salary or benefits.

It may seem churlish that I’m nitpicking the internal credibility of It Ends with Us; after all, wasn’t it just last week that I happily ignored the logistical dubiousness of M. Night Shyamalan’s Trap? But the movie’s surface-level depth is frustrating because it diminishes the power of its message, which is nonetheless quite meaningful. Baldoni is careful to frame the proceedings from Lily’s point of view, and his nerviest move is to make Ryle’s actions a point of ambiguity; the first instance of assault that we witness, in which he strikes her face while yanking his hand back from a burning frittata, is staged to appear as though it really might have been an accident. By presenting Ryle as an ostensibly decent man plagued with deep-seated volatility rather than as a black-hearted monster, the film lets us understand how Lily might fall under his spell, and how challenging it is for her to perceive the danger he poses to her welfare.

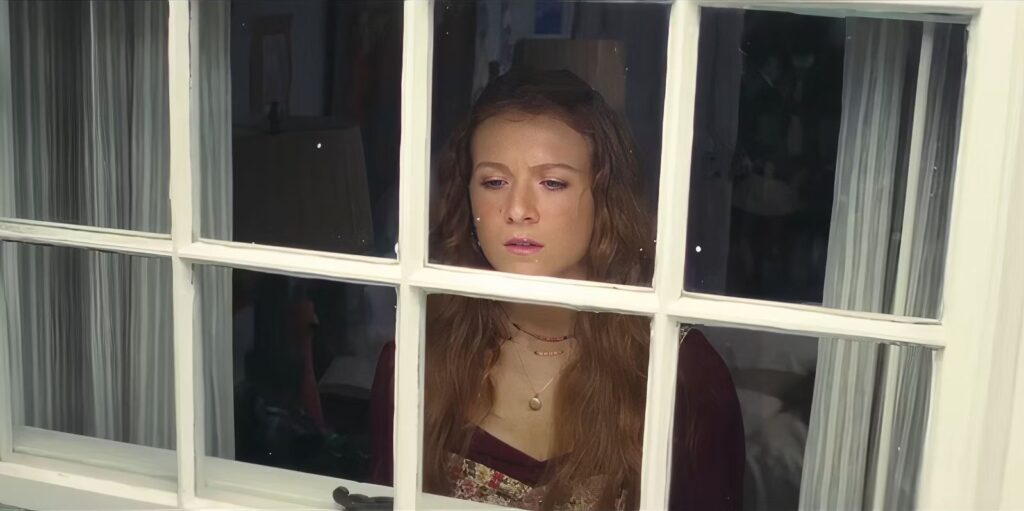

Speaking of danger, it’s vaguely perilous for It Ends with Us to treat Ryle with a measure of complexity; in essence, he’s the movie’s only three-dimensional character, whereas Lily is primarily defined by her passivity and her victimhood. But she remains the story’s heroine, and Lively’s performance is satisfying for how she allows Lily to quietly assert her independence without resorting to histrionics. A late scene in a hospital room, which ought to serve as the picture’s ending, is lovely for its rich tangle of emotions—the way it mingles affection and admiration with regret and resolve.

The notion that abusers can be wolves wearing doctors’ clothing might not shock social scientists, but it’s the kind of idea that rarely makes its way into mainstream cinema. I don’t think It Ends with Us is a great movie; its universe is too contrived, and its themes don’t fully harmonize with its characters. But I’m glad it’s making money, because it’s precisely the type of movie I wish studios would make more often: mature, humane, sincere. Critics like to imagine a utopia where the modern multiplex centers stories for adults alongside the superheroes and the franchise fare, and the success of It Ends with Us suggests that might not be a fantasy after all. Maybe it starts with this.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.