Jason Reitman likes two things: chaos, and smart people overcoming it. Aaron Eckhart’s amoral lobbyist in Thank You For Smoking, Elliot Page’s arch teenager in Juno, George Clooney’s slick consultant in Up in the Air—they were all sharper than everyone else, and their superior intellect helped them navigate sticky situations. So it makes sense that Saturday Night, Reitman’s brisk and entertaining and somewhat dubious recreation of the inaugural production of Saturday Night Live, centers on a brilliant young man ensnared in a thicket of logistical complications. Can our clever and resourceful hero somehow beat the odds and get the show ready for air?

You surely know the answer to that question, even if the abbreviation “SNL” is somehow foreign to you. Reitman, who co-wrote the screenplay with Gil Kenan, has structured the movie as a ticking-clock thriller, but it really unfolds in the language of the underdog sports drama. The cast and crew of the show’s production resemble a ragtag batch of hotheaded athletes and quirky assistants, a fragmented bunch whose clashing egos and disparate abilities must be marshaled by the beleaguered head coach into a unified team. The putative suspense derives from whether this unruly squad can put aside their differences and assemble a functional variety hour—can score a goal, as it were—before the final buzzer that’s destined to go off half an hour before midnight.

The young man at the center of this maelstrom is Lorne Michaels (Gabriel LaBelle), the ambitious producer who has seized on a contractual dispute between NBC and Johnny Carson and has somehow convinced the network to give his untested troupe of comic brawlers a 90-minute slice of late-night TV real estate. Saturday Night opens with a title card quoting Michaels (“The show doesn’t go on because it’s ready, the show goes on because it’s 11:30”), and that winking adage isn’t the last time it venerates its protagonist, who’s referred to at one point as a wunderkind. Still, LaBelle plays this Lorne less as an omniscient genius than a perpetually harried grifter, one who repeatedly wields his quick wit and silver tongue in an effort to solve a never-ending series of daunting practical problems.

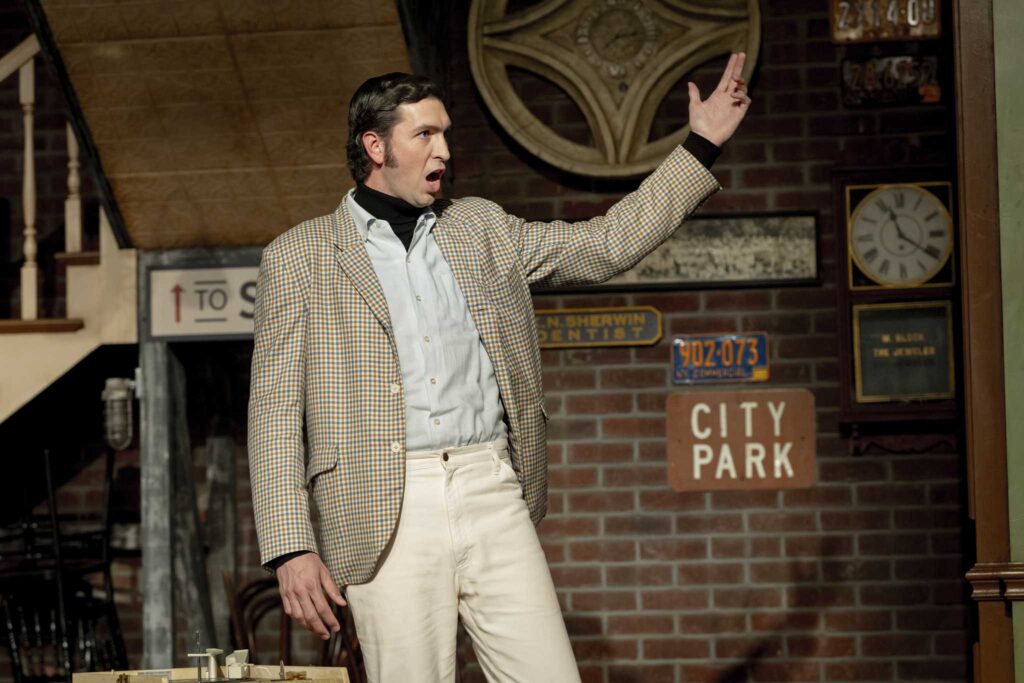

And there are plenty of those crammed into the movie’s 100-odd minutes (which purport to follow a real-time trajectory beginning at 10 p.m., but don’t get hung up on clock-watching). John Belushi (Matt Wood) still hasn’t signed his contract. He’s also constantly fighting with Chevy Chase (Cory Michael Smith), who seems more interested in parading his gorgeous new fiancée and impressing NBC bigwigs than in rehearsing his sketches. (One executive’s positive appraisal of Chase: “You’re a handsome, funny gentile.”) Lorne’s wife, Rosie Shuster (Rachel Sennott), is unsure whether to credit herself with his or her surname, a trivial crack that hints at deeper fissures in their marriage. Jim Henson (Nicholas Braun, who also plays Andy Kaufman in what I can only assume is an inexplicable meta joke) keeps complaining about his animal props, which the rest of the cast are only too happy to abuse. George Carlin (Matthew Rhys) is swearing up a storm, making him but one of many targets for the ire of an officious censor (Catherine Curtin) who insists on sanitizing everyone’s jokes. A lighting rigger quits, the speakers don’t work, and a pile of bricks collapse into literal rubble. Oh, and turns out the whole show might just be a ploy designed to give the network leverage in their ongoing negotiations with the King of Late Night himself (played via voiceover by Jeff Witzke), whose old taping is cued up to play in case the main suit (Willem Dafoe) deems Lorne’s live program unready for air.

Your level of interest in these predicaments is likely to hinge on the extent of your immersion in SNL lore. (I’m a relative neophyte; I know David Pumpkins and “Celebrity Jeopardy” and the Lonely Island, but I can’t recall ever watching an actual episode of the series.) With its ’70s wigs and prosthetic facial hair and sweaty impressions, Saturday Night is inherently performing a certain type of fan service, treating loyal followers to glimpses of the beloved celebrities (hey look it’s Jane Curtin! wait, is that supposed to be Billy Crystal?) whom they’ve watched on weekend evenings over the past half-century. There’s nothing wrong with this—it’s endemic to any fact-based recreation of the entertainment industry—but it does lend the movie a certain self-satisfaction, as though simply littering the screen with as many recognizable players as possible grants aficionados the pleasure of filling out their SNL bingo cards. (A late scene in which Lorne impulsively recruits the writer Alan Zweibel has no apparent narrative purpose beyond featuring Alan Zweibel.) It keeps lighting up the applause sign and demanding your kudos.

As if anticipating accusations of pointless mimicry, Reitman attempts to compensate with pure speed, thrusting viewers into a hectic blizzard of famous faces, period costumes, and nonstop overlapping dialogue. Visually, the movie is pretty ugly, with a wan color scheme and jittery cinematography; there are a few immersive handheld tracking shots, but mainly it just feels like someone is sprinting after Lorne without quite knowing where to point the camera. Verbally, Reitman and Kenan fare better, and if their script lacks the musical zing of peak Aaron Sorkin (an obvious touchstone), their high-quantity approach at least delivers its fair share of playful exchanges and solid one-liners.

And what of the performers charged with reciting such pithy wordplay? Even in its infancy, Saturday Night seems to have emerged in the form of a fossilized artifact, a picture that future generations might look back on as launching the careers of a tribe of hungry young actors. That reading discounts their prior work—Sennott is already something of a minor star, while LaBelle, who shined in both The Fabelmans and this year’s Snack Shack, seems destined for a similar ascent—but they’re both quite watchable here, as are Smith, Wood, a vivacious Ella Hunt (as Gilda Radner), and a scene-stealing Tommy Dewey (as head writer Michael O’Donoghue). Reitman also can’t help but surround his mostly unproven cast with a few distinguished veterans, most memorably J.K. Simmons, who portrays Milton Berle as a fabulously repellent asshole. (When Chase insults him, Berle responds, “If you want my comeback, you can scrape it off the back of your mom’s teeth.”)

Even if the few snippets of sketch comedy we do see are, well, pretty sketchy, Saturday Night is a largely pleasant viewing experience. But thematically speaking, the movie is oddly grating—maybe even fraudulent. On its face, it’s telling the triumphant story of a band of scrappy, striving artists who overpower the entrenched, stuffy establishment through the sheer force of their undeniable talent. Yet it’s really doing the opposite, paying fervent tribute to its famous subjects and worshipping at the altar of a mighty institution. There is even a whiff of scripture to it, a sense that it’s preaching the gospel of a messianic genesis. This doesn’t make Saturday Night a bad time, but it does diminish its vigor, because we’ve seen these sorts of creation myths before. Funny how a movie about the show that changed television forever ends up feeling like just another rerun.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.