Bathed in ghostly white moonlight, a man stands in the center of a black roadway lined with forest-green pines. In the distance, he spots the faint outline of a moving object, which he gradually perceives to be a horse-drawn carriage. As the animals gather velocity and momentum, he realizes that he’s about to be trampled. He shuts his eyes and braces for impact, only to realize that the vehicle has magically stopped and angled itself perpendicular to him, its door thrown open, beckoning him into the waiting darkness. And then the coachman calls out, “Did you order an Uber?”

I made that last part up. The vampire mythos, with its lustful symbolism and its gargled accents, is easily vulnerable to ridicule. And there are certainly times when Nosferatu, Robert Eggers’ sumptuous remake of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 touchstone, dances up to the cliff’s edge of parody. But what rescues it—what turns your stifled laughter into shrieks of horror and gapes of wonder—is that it approaches its material with absolute sincerity, and without a shred of irony or detachment. Eggers, undertaking the perilous task of updating a 102-year-old classic, has of course renovated the silent black-and-white original, imprinting it with intoxicating sound and color. Yet he has not sacrificed any of its elemental power, forgoing the temptation for winking archness and instead operating with brazen, old-fashioned conviction.

And also new-age craft. Again working with the cinematographer Jarin Blaschke, Eggers has concocted a gripping visual schema that is both chillingly malevolent and hauntingly ethereal. That aforementioned shot of a solitary traveler standing on a desolate road is but one of many exacting compositions which expertly juxtapose light and darkness. As befits a horror picture, Nosferatu’s palette is often dusky, but it isn’t murky; instead, Eggers and Blaschke are purposeful in what they withhold and what they reveal. Straight from the outset—the cold open finds a virginal young woman sleepwalking on the grounds of her manor and pledging herself to an unseen creature, her white gown flowing in the midnight wind—the movie’s aesthetic is operatic. This degree of grandeur extends to all components of the film’s production: Craig Lathrop’s set design, with its vast fortresses and Gothic alleyways, is appropriately baroque; Linda Muir’s costumes are fabulously frilly; Robin Carolan’s throbbing score, what music it makes.

The sheer weight of this artistry demands a commensurately sweeping narrative to support it. You already know the story, even if you haven’t seen Murnau’s original (which was an unauthorized adaptation of Dracula) or Werner Herzog’s 1979 update (which I remain sadly ignorant of): Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult, putting a Christmas bow on a very fine year), an enterprising real estate agent eager to prove himself, accepts an assignment requiring him to travel to Transylvania, where he must secure the signature of a mysterious recluse named Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård). He leaves behind his new wife, Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), a fragile thing prone to fainting spells, inexplicable seizures, and somnambulism. As Thomas plunges deeper into the foreboding catacombs of the Count’s castle, Ellen’s symptoms grow increasingly severe, a deterioration that somehow seems linked to Orlok’s sinister whispers.

The opening passages of Nosferatu are its creakiest. Thomas’ journey through the Carpathians leads him to a Romani village whose peasants engage in bizarre rituals; their primitive practices are only thinly connected to the main plot, and the interlude lacks the supple majesty that Eggers supplies elsewhere. The pace picks up a bit once Thomas encounters Orlok, whose face Eggers intentionally shrouds for an extended period. (The amusing exception occurs when Thomas cuts his finger and Eggers cuts to a close-up of Orlok’s eyes bulging with hunger.) More interesting and unsettling are Ellen’s travails back home in Germany, where she suffers through bouts of anxiety that prove to be less harmful than carnal.

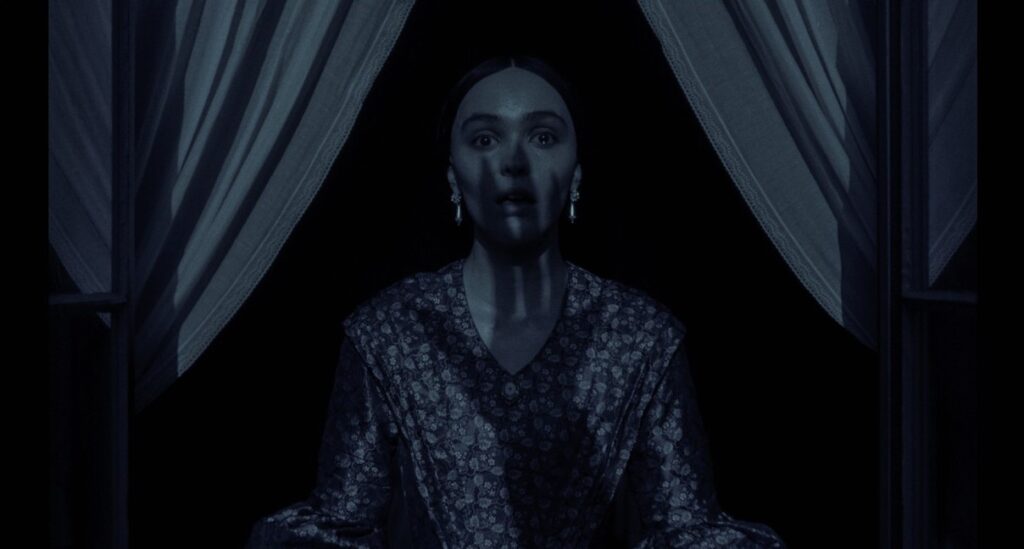

Vampirism is inextricably bound up with sex—the obsessive need to possess someone, the notion of gaining life by feeding on another’s flesh—and this Nosferatu’s treatment of Ellen’s suppressed lust is positively indecent. “He spreads his shadow,” she pants at one point, constantly prophesying that “he is coming”; talk about w(h)etting your appetite! Later, she flings herself on her knees, her head pressed against her husband’s crotch, before looking up and taunting him that he’s an inferior lover; this leads to a sex scene that nervily commingles ecstasy and brutality. Throughout the movie, Ellen moans and heaves and spasms, her body contorting into inhuman positions, her voice sighing with a mixture of pain and longing. She exists in a state of perpetual excitement, and when it comes to the beast who stalks her, it’s unclear whether she wants to fight him or fuck him.

Eggers, using practical effects and dastardly editing, is only too happy to put Depp’s face and form through the wringer. (It’s tempting to imagine what Anya Taylor-Joy, Eggers’ first muse and initial choice, might have done with this role, but Depp’s physicality is nonetheless persuasive.) Yet while it’s understandable to characterize Nosferatu first and foremost as a visual feast—the shot of a giant shadow in the shape of Orlok’s clawed hand metaphorically exerting its grasp over the entire city is dazzling, as is the dissolve where the back of a vampire’s head somehow turns into Ellen’s visage—the movie also excels on another, more surprising level: It is a triumph of dialogue.

Then again, this is perhaps less surprising than you’d think. Four features into his career, Eggers’ setting has never advanced past the 19th century, and he has consistently aligned the rhythms of his screenplay to the period of the vernacular; no contemporary filmmaker is more committed to wielding modern cinematic tools in the service of antiquarian language. The plot of Nosferatu may be simple and familiar, but the words that the characters speak are flavorful and new, and the richness of their verbiage lends further elegance to a movie that’s already dripping with sensation. At one point, Orlok invades Ellen’s dreams (he does that a lot, actually) and threatens to devour her loved ones unless she surrenders to his will; the sequence is beautifully staged (the camera glides around the shadowy walls with fluid precision), but it’s also verbally invigorating—a fraught tête-à-tête of demonic manipulation.

Depp and Hoult prove capable of articulating such ornate dialect, while Skarsgård twirls his tongue around every syllable like he’s savoring morsels of haute cuisine. (He occasionally sounds like Kayvan Novak from What We Do in the Shadows, but there’s nothing funny about his looming frame or his revolting makeup.) Yet the actor who proves best suited for Eggers’ silky wordplay is Willem Dafoe, who previously starred in The Lighthouse and had a supporting part in The Northman. Playing a Van Helsing surrogate called Prof. Albin Eberhart Von Franz (wahoo!), he shows up halfway into Nosferatu and immediately kicks things into another gear, recognizing the absurdity of the material but never condescending to it. (Dafoe has a meta connection to this universe, having appeared in Shadow of the Vampire, where he played… Max Schreck, the actor who portrayed Count Orlok for Murnau. Yikes.) The tested marriage between Ellen and Thomas is nominally touching, but it’s the scenes between Ellen and Von Franz—the doctor understanding the depths of his patient’s trauma and his inability to rid her of it—that lend the movie its quiet tenderness.

Which is not, to be sure, its primary emotion. But what is? Not fear; despite a few hoary jump scares and some dream-scene fake-outs, Nosferatu isn’t especially terrifying. It’s more a work of extravagant beauty, gorgeously conveying the all-consuming agony of desire. No doubt that’s a recognizable theme, but it’s rarely been manifested with such creativity and style. Technically speaking, Eggers may have simply remade an old movie. But with lush images and vivid words, he has infused the vampire genre with fresh blood.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.