Sad Men: Does Don Draper Finally Find Peace in the Mad Men Finale?

And at long last, Don Draper has died.

No, he didn’t fulfill a popular fan theory and jump out of his office building as pictured in the long-running opening credits. He didn’t die in the middle of a pitch, as his friend and mentor Roger Sterling had predicted. He didn’t die of lung cancer (though his ex-wife soon will). And, most mercifully, he didn’t get shot in the back of the head like what maybe happened to that other guy Matthew Weiner used to write about. But while the final scene of The Sopranos—the show on which Weiner cut his teeth, writing episodes as far back as 2004—will be debated pointlessly until the end of time, Mad Men‘s finale demonstrates the insignificance of that discussion. The Sopranos possibly ended with the death of Tony Soprano’s body. Mad Men concluded with something far more terrifying: the death of Don Draper’s soul.

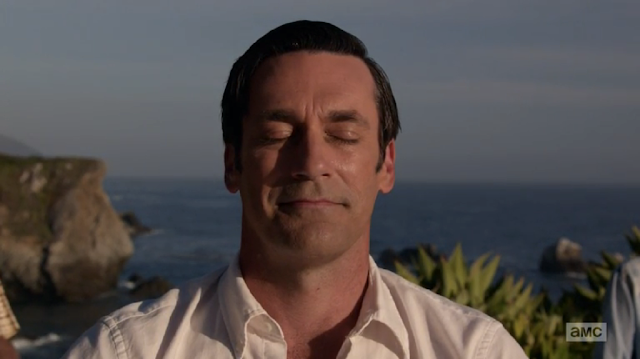

That, of course, is just one interpretation. Undoubtedly, a pocket of viewers will insist that Don didn’t dream up the Coca-Cola ad that played this majestic series off the air, that he’s still meditating peacefully out in Big Sur, that the show’s final image of his lips curling into a smile proves that he finally found true enlightenment, not that he’d just experienced an epiphany on how to sell soft drinks. And maybe they’re right. Maybe that final chime wasn’t the sound of another lightbulb going off in Don Draper’s head, the instinctive response of a man who built himself into an executive of such towering potency—the man from the opening credits who tumbles from the top of a skyscraper, then suddenly reemerges, sitting confidently in his armchair—that he reflexively transforms human feelings into ad sales. Maybe Peggy wrote the Coke ad.

But I can’t accept that reading, because it doesn’t square with the Don Draper whom I’ve followed over the past seven seasons. That Don didn’t even start out as Don—he was Dick. But then a cigarette lighter collided with a puddle of fuel, and from the ashes sprang Don Draper, advertising genius. He knew he was living a lie, and he was forever haunted, not just by the terror of being discovered (recall the opening dream of the penultimate episode, when the cop bluntly informs Don, “You knew we’d catch up with you eventually”), but by the possibility that all of the monumental effort he’d expended to build his life anew was meaningless. “I took another man’s name,” he confesses to Peggy, his protégé and most faithful friend, “and made nothing of it.”

That’s a matter of opinion—Peggy vehemently disagrees, and if nothing else, Don fathered three kids with Betty, the oldest of whom is pretty awesome—but Don certainly believes it. It’s why he recently decided to repeat history and reinvent himself once more. These last few episodes of Mad Men involved Don stripping himself of the artifices that he accumulated upon his return from Korea. He quits his job. He gives his Cadillac to a hustler and admonishes him, “Don’t waste this.” He tracks down Stephanie, his de-facto niece, and offers her Anna’s old ring, a family heirloom. But he isn’t getting the rebirth he wanted; instead, he’s overwhelmed with grief and regret. “You’re not my family,” Stephanie spits at him, and the words are like a knife to the gut. Betty has already told him, quite accurately, that their children are accustomed to his absence, that his return home would only upset them. So, what now? If he isn’t Don Draper anymore, who is he?

Enter Leonard.

Now, every season of Mad Men has featured memorable monologues, but they’ve invariably belonged to Don, that artful manipulator of language. Whether he was filtering images of his home life through Kodak’s Carousel in “The Wheel” or revealing his impoverished origins to the Hershey’s execs in “In Care Of”, Don’s eloquent dialogue formed the backbone of Mad Men‘s biggest moments. But he was almost always talking, not listening. So it took some serious stones for Weiner to write one of his grandest, saddest speeches for the finale, then give it to someone we’ve never even met before. And while I can’t pretend that I expected a significant portion of Mad Men‘s final episode to take place at a California ashram, my bafflement proved unfounded once a soft-featured, middle-aged man shambled to an empty chair and started talking. Read More