Fly Me to the Moon: Give Me a Fake

Remember movie stars? Those fabulously attractive celebrities who compelled audiences to flock to theaters in droves by sheer virtue of their names appearing on the marquee? They’re back in Fly Me to the Moon, a fizzy, fitful romantic comedy stocked with bright colors, lithe bodies, and a smattering of funny lines. It’s set in the ’60s and could have been made then too, even if its throwback vibes are often as clumsy as they are charming.

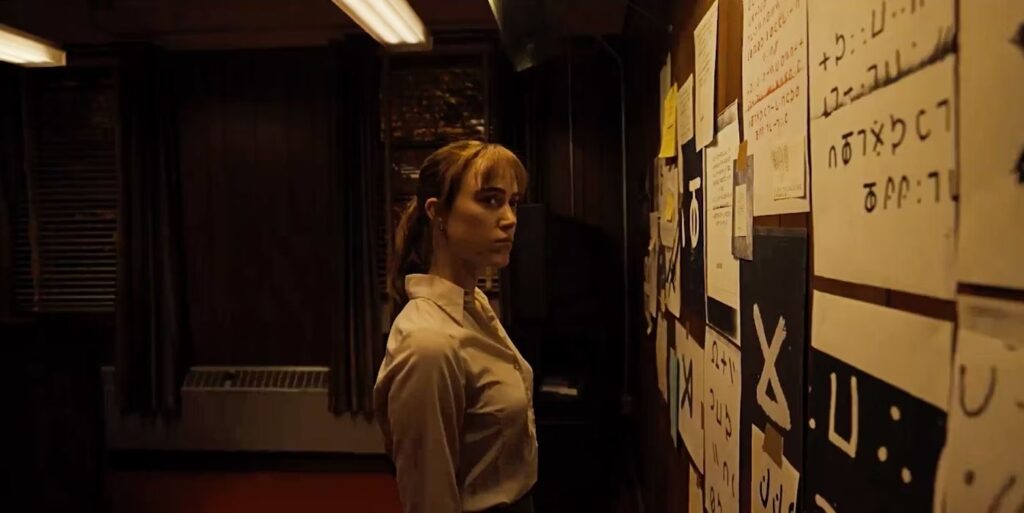

In the spirit of plucky wholesomeness that the movie tries to evoke, let’s start with the good stuff: Scarlett Johansson and Channing Tatum. And also Scarlett Johansson and Channing Tatum’s clothes. The costume designer, Mary Zophres (a regular collaborator with both Damien Chazelle and the Coen Brothers), develops the film’s characters with greater efficiency and style than Rose Gilroy’s clunky screenplay. Tatum, with his bull neck and broad shoulders, is outfitted in an array of tight-fitting sweaters that convey the swelling frustration of a robust leader whose vision is thwarted by external forces. Johansson, in contrast, is the picture of crisply tailored elegance, gliding through the picture in pastel dresses that accentuate her authority as well as her curves. Read More