Can a movie be exhilarating and tedious at the same time? Elvis, the biopic about an American icon (Elvis Presley) from an Australian director (Baz Luhrmann), is a vigorous and exhausting work, 159 minutes of bright lights and raucous noise and extravagant camera moves. It is also oddly boring, struggling to derail itself from the rigid train tracks that most pictures of its ilk travel upon. It has become fashionable, and a bit too cute, for critics to deride docudramas of musical genius as unwittingly earnest reproductions of Walk Hard, the 2007 parody that skewered the genre with John C. Reilly singing ditties like “You Got to Love Your Negro Man.” Elvis is too vibrant and enthusiastic and just plain expensive-looking to be dismissed as repetitive boilerplate. Yet its story—of greatness discovered, burnished, troubled, and exploited—is too typical to be memorable.

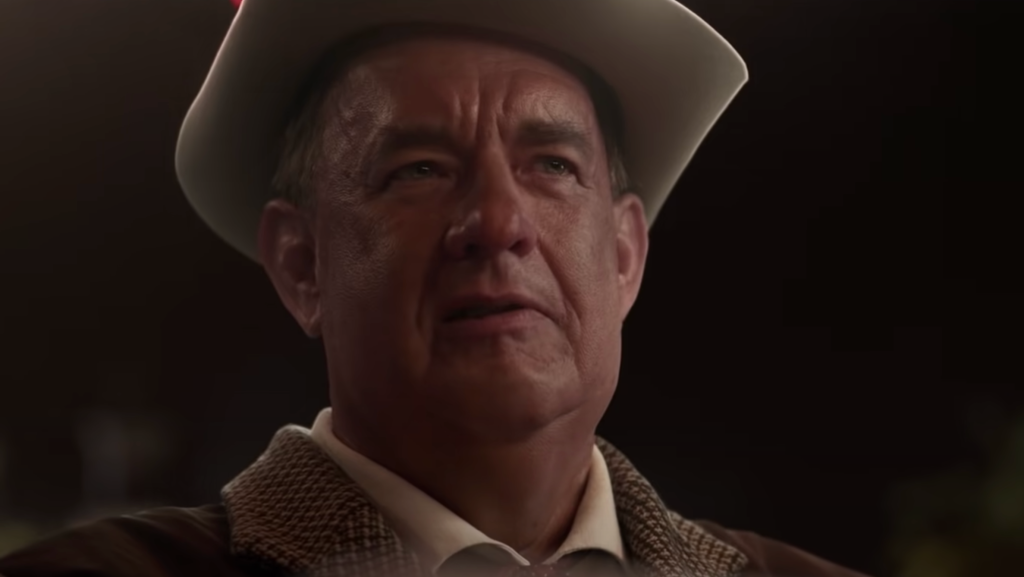

Its narrative trajectory may be tiresome, but visually speaking, Elvis is not dull. Never one for restraint, Luhrmann hurtles through his material with aggressive, often excessive verve, stitching together cacophonous sequences with music-video impatience. There are times, especially during the opening act—which finds the louche Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) narrating the film’s events in flashback as he lies in a hospital bed and imagines himself wandering through garish casinos with a drip in his arm—when this hyperactivity can feel overwhelming, like a Broadway production by way of Michael Bay. Still, the movie’s style is consonant with its subject, creating a feedback loop of restless energy. It’s fitting, if perhaps predictable, that Elvis feels most alive whenever Elvis is on stage feeling lively.

“If I can’t move, I can’t sing,” Elvis (Austin Butler) grumbles at one point, and one suspects that Luhrmann suffers from a similar affliction. Yet despite all of its relentless motion—the toggling between timelines, the cutting across vantages, the pivots and zooms and crane shots—Elvis snaps into focus during its performative scenes. The most memorable of these is a nigh-mythical birth sequence—in case you missed the metaphor, Parker supplies it via voiceover—at a Louisiana hayride in 1955, when Elvis croons “That’s All Right” and uncorks his trademark pelvic wiggle (“What’re they hollerin’ at?”), sending his female onlookers into fits of orgasmic hysteria. (I considered questioning the credibility of such a biological response, but then I remembered watching Britney Spears cover “Satisfaction” at the 2000 VMAs.) Luhrmann’s choreography of this sequence is characteristically boisterous, but his natural exuberance matches the feverish pitch of the crowd, and the result is electric.

What follows is rather less hypnotic, though Luhrmann is gracious enough to periodically integrate similar renditions over the story’s 18-year period. Parker, a venal entrepreneur with a white straw hat and a silver tongue, seizes control of Elvis’ musical career like a farmer fattening his livestock. (Parker opens the film managing the country crooner Hank Snow, and a nifty montage displays his new golden goose’s rapid ascent of their tour’s billing.) From there, well, you know the rest. Their initially fruitful partnership will gradually grow rancorous, leading to contractual disputes and splintering mistrust. Various illicit substances will be abused. A beautiful woman (Olivia DeJonge, most recently seen on HBO’s The Staircase) will show up, only to be quickly neglected per the stresses and obligations of fame. The hero’s meteoric rise will be followed by a cataclysmic fall.

If I sound a bit frustrated by this conventionality, it’s because Elvis represents another example of its director spotlighting his gifts while failing to fully capitalize on them. Luhrmann’s magnum opus remains Moulin Rouge, in which he assembled virtually every pop song composed in the 20th century and arranged them into a buoyant and glitzy medley that served as the sonic and emotional backbone for a heedlessly transcendent romance. His subsequent features—the goofy but enjoyable Australia and the dubiously conceived, frequently entertaining adaptation of The Great Gatsby—were whirls of mania and craft, treating viewers to impressive sights of high-toned spectacle but never quite figuring out what to do with their characters. Elvis is arguably his most disappointing work, not because it fails to deliver moments of amazement but because it squeezes those moments into such a boxy and formulaic package.

Which doesn’t mean it’s devoid of innovation. Luhrmann manages to bring some flair to otherwise prosaic plot-moving scenes; there’s a nifty sequence that juxtaposes Elvis’ crowd-pleasing Vegas shows with Parker’s serpentine negotiations with a hotel manager (he scrawls an unscrupulous contract onto a cocktail napkin), while the Faustian scene where Parker initially seduces Elvis with whispers of stardom takes place in a malevolent hall of mirrors, throbbing with such menace that it could have been yanked from a horror movie. Parker would doubtless claim that he’s responsible for nurturing that stardom, but Luhrmann seems to view it as simply god-given, which is why he dispenses with cataloguing Elvis’ creative process and instead envisions him as a prodigy whose greatness sprang from his soul; he cleverly underlines this conception with a quick flash to the artist’s youth, when the spirit takes hold of him at a gospel revival.

Nor is the film’s orthodoxy entirely unpleasant, given that it leans into a rich cinematic tradition of affording talented actors the opportunity to showboat. Hanks, our paragon of human decency and moral authority, relishes the chance to play a heavy so unrepentant that he demands reimbursement for $1.25 in gas money; if the performance lacks subtlety (and features a silly, vampiric accent), that’s only because it dovetails with Luhrmann’s maximalism. As for Butler… hey, who the hell is Austin Butler, anyway? A television bit-timer whose prior big-screen legacy was setting up Brad Pitt’s funniest line in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, the 30-year-old unknown was a risky choice to headline such a big-budget project. Whether he accurately mimics Presley’s rangy voice (he sings early in the picture, while later scenes blend his vocals with the King’s archival recordings) and signature gyrations are better debated by music historians than movie critics. What I can say is that, aided by Catherine Martin’s sharp and colorful costumes, Butler embodies a very particular type of charisma—soulful and alluring, yes, but also a little dangerous. When his Elvis approaches the mic, you lean forward, sensing that you’re about to watch something forbidden.

Which, all told, you rarely get. One of the movie’s subplots involves the government’s distaste for Elvis’ gesticulative flamboyance, and its efforts to throttle his artistic expression in the name of civility. No one could reasonably accuse Luhrmann’s filmmaking of being polite, but while Elvis posits itself as mounting a proud defense of lewdness and obscenity—one byproduct of framing Parker as such a heel is that it casts Elvis’ attempts to defy him, as in a ludicrous episode involving a Christmas special, in a rebellious and celebratory light—it is ultimately too cautious to be revolutionary. It proceeds roughly as you expect it to, which means it’s yet another entry in the long procession of venerable musical hagiographies. It may possess some stylistic swagger, but in the end, it ain’t nothin’ but a biopic.

Grade: B-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.