A Quiet Place: Staying Alive, with Mouths Shut and Eyes Open

We begin with a stark title card: “Day 89.” A family prowls through a deserted pharmacy, the mother scanning labels on vials while the kids amble through the aisles and pluck goodies from the shelves. It’s a familiar scene to fans of apocalyptic fiction, the dusty sills and sparse surroundings recalling similarly ominous openings from movies like 28 Days Later and I Am Legend. The key difference here is that the characters, plainly well-versed in this foreboding new normal, take special care not to make any noise whatsoever. Yet before long, a mistake is made, a sound is blared, and in the blink of an eye and the rustle of some leaves, a life is taken.

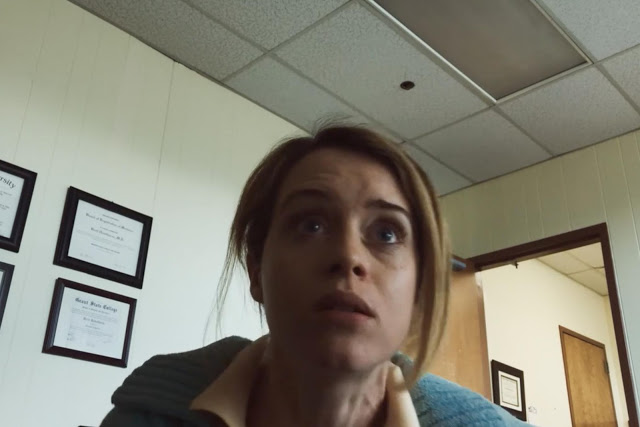

And with this brief and riveting and ghastly cold open, A Quiet Place announces itself as an expertly conceived and executed horror film, perhaps the best of its kind since It Follows. Combining a knockout premise—stop, hey, what’s that sound?—with white-knuckle set pieces and a bracing degree of economy, the movie both elevates your pulse and digs under your skin. It’s scary, sure, but not so scary that it prevents you from admiring it as a polished, fiendishly inventive piece of pulp art. Read More