Sausage Party: Imagine All the Foods, Losing Their Religion

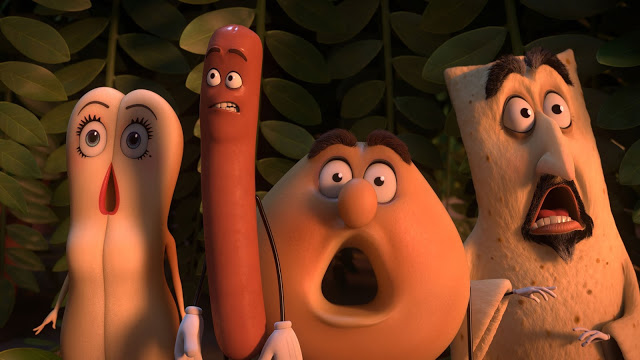

The community at the center of Sausage Party is a vibrant melting pot, a diverse cross-section of ethnic backgrounds and religious faiths. But this neighborhood is also unified in its theism—although it hosts a number of different sects, most of its residents believe in some higher power. Some sing hymns together, while others pass down oral histories of their divinities; virtually all of them contemplate the existence of life after death and hope one day to ascend to a spiritual plane. In essence, this bustling hub of worship exhibits the kind of cultural variety that you might find in any American metropolis, where people regularly attend churches, synagogues, or mosques. There’s just one small difference that distinguishes the characters of this movie: They’re all foods.

The premise of Sausage Party, which was co-written by longtime best buds Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, sounds like an idea that they cooked up while getting stoned on the set of This Is the End, their woozy apocalyptic hangout comedy. (Virtually the entire voice cast of Sausage Party appeared in that film, while Kyle Hunter and Ariel Shaffir, who both executive-produced it, also receive screenwriting credits here.) That movie used the Rapture as scaffolding for a thoughtful investigation of male friendship and insecurity, and Sausage Party features an even crazier concept that masks an even more provocative study of human behavior. Curiously, it’s the latter that leaves a mark. A self-professed work of “adult animation”, Sausage Party is frequently funny and persistently filthy, but its commitment to excess suffers from diminishing returns. It’s the skewering of organized religion that really stings. Read More