Richard Jewell: A Bomb Detonates, and a Life Explodes

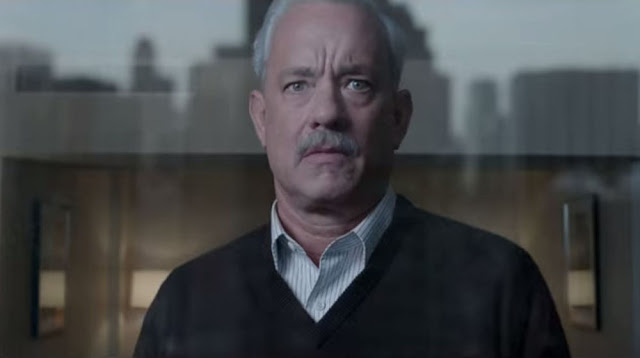

Even when they aren’t appearing in Westerns or war films, Clint Eastwood’s heroes routinely find themselves under siege. Earlier in his everlasting late period, in movies like Invictus and J. Edgar, Eastwood’s principals operated from inside the government, attempting to impose order and decency on a cruel and lawless world. Lately, however, The System itself has become Eastwood’s chief antagonist, a daunting power intent on smearing the names and ruining the lives of good men. In Sully, a skilled and noble pilot found himself the target of a biased and insidious bureaucratic inquiry. Now comes Richard Jewell, which dramatizes the 1996 Atlanta Olympics bombing and its aftermath, when the country collectively decided—based on hunches rather than evidence—that the doughy security guard who thwarted the attack was in fact the man who perpetrated it.

This material—an innocent man, railroaded!—is catnip for Eastwood, which means it plays to his worst instincts. Yet while Richard Jewell is clumsy and dubious, it is also fleet and colorful, featuring some of the director’s most relaxed and immersive filmmaking in years. It would be terrible if it weren’t so enjoyable. Read More