In the dreadful 2012 flop Trouble with the Curve, Clint Eastwood plays a grizzled baseball scout who has grown disgusted with the sport’s increasing reliance on analytics and technology. “Anybody who uses computers doesn’t know a damn thing about this game,” he growls at one point. His irascible critique encapsulates the film’s worldview, namely, that the classicist’s wisdom of observational experience will always vanquish the modernist’s reliance on statistical data. That broad thesis is now the animating force behind Sully, Eastwood’s brisk, hackneyed, intermittently diverting reenactment of an American tragedy that wasn’t. It’s the kind of movie where the officious villains blindly trust computer simulations, only to be taken aback when they’re informed that they’ve failed to account for that most vexing of variables: humanity.

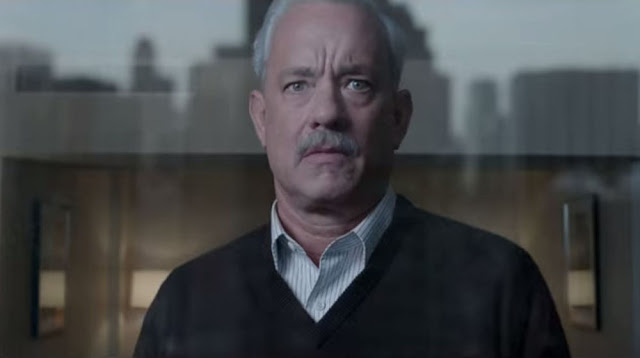

The majority of the humanity in Sully derives from Tom Hanks, an actor who, luckily for Eastwood, could imbue a paperclip with an aura of moral and professional authority. Here he provides the necessary blunt-force gravitas as Capt. Chesley Sullenberger, the pilot better known as, well, you know. The film opens with anonymous voices screaming Sully’s name as an airplane glides above the streets of Queens before crashing into a skyscraper. It’s a nightmarish image, which makes sense, given that it is born from Sully’s nightmares. In actuality, as you will no doubt remember, things went quite differently: On January 15, 2009, after U.S. Airways Flight 1549 suffered power failure in both engines due to bird strikes, Sully successfully landed the plane on the Hudson River, saving the lives of all 155 souls on board. The incident was swiftly dubbed “the Miracle on the Hudson”, with Sully as its chief architect. Roll credits.

OK, not so fast. Sully, whose screenplay is by Todd Komarnicki (adapting Capt. Sullenberger’s own book, The Highest Duty, which he wrote with Jeffrey Zaslow), purports to delve deeper into the putative miracle that inspired it. Did Sully really need to land in the water, thereby risking disaster? Couldn’t he have just returned the plane safely to LaGuardia Airport? What about Teterboro Airport in New Jersey, located just on the other side of the George Washington Bridge, a mere seven miles away? Yet while Sully feints at questioning the legitimacy of its protagonist’s legacy, what it really wants to do is cement it. This makes the project, aspirationally speaking, both noble and strangely dubious. I myself was unaware that Sully was viewed by the public as anything other than an honest-to-goodness American hero. What’s the point of making a movie that simply reiterates what we already knew?

But I probably shouldn’t question Eastwood’s artistic motivations, and besides, some of the material here is, if not essential, certainly compelling. At its best, Sully emulates its title character, chronicling Flight 1549’s all-too-brief journey with lucid, workmanlike cogency. Eastwood’s no-frills style feels right here, and while the film’s centerpiece cannot rival the pièce de résistance from Robert Zemeckis’ Flight—easily the gold standard for white-knuckle airborne suspense—it compensates with smart editing and sure attention to detail. On the plane, Eastwood creates a tense environment that pulses with fear but which also carries a strong sense of professionalism, from Sully tersely discussing options with his copilot (Aaron Eckhart, wearing a mustache well) to the flight attendants instructing the passengers to “Brace! Brace! Brace!” for impact. He also gently expands the scope of the event and considers those on the ground, including a skipper of a nearby ferry and—in the movie’s most quietly poignant arc—an air traffic controller (Patch Darragh, excellent) who becomes despondent once he learns that the flight is headed for the Hudson, certain that it’s doomed.

Those are nice grace notes, and they make it difficult to judge Sully too severely, given how it paints such a warm picture of post-9/11 New Yorkers banding together in a time of crisis. As a director, Eastwood can occasionally flirt with jingoism—American Sniper was (wrongly) chastised by some as a militaristic propaganda piece—but the patriotism on display here feels earnest and earned. The movie’s depiction of the immediate aftermath of the aircraft’s landing is fascinating—just how do you transport 150-plus people from the middle of a frigid river before they freeze to death?— but in illustrating the Big Apple’s sense of unity, it is also heartwarming. It would feel like corny wish-fulfillment fantasy, except it happens to be true.

But this is not enough for Eastwood. The real meat of Sully is not the water landing itself, but the ensuing investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board, the government agency tasked with reviewing the incident. You’ve seen the NTSB on screen before: In Flight, it was personified with chilly intelligence by Melissa Leo as an accident reconstructionist who admired Denzel Washington’s bravura mid-flight maneuvers but was less enamored of his blood alcohol content. Leo’s character had a heart of flint, but she’s an absolute softy compared to the triumvirate of NTSB investigators portrayed here. Each played by an accomplished television actor—including Mike O’Malley (Justified, Yes Dear), Jamey Sheridan (Law and Order: Criminal Intent), and Anna Gunn (Breaking Bad)—they are paradigms of petty vindictiveness and bureaucratic venality. Forget the search for truth; these three seem genuinely determined to prove that Sully behaved improperly, diving for the Hudson in a narcissistic quest for glory when a simple U-turn to LaGuardia would have done just fine.

Unsurprisingly, the NTSB has objected to the movie’s characterization of the agency as a McCarthy-esque brute squad. But the accuracy (or lack thereof) of Sully‘s representation is beside the point. Every biopic is entitled to distort the historical record in order to generate drama and excitement. The problem with Sully‘s departures from fact is that they serve to manufacture a conflict that feels wholly engineered. The extremity of the investigators’ attitudes robs the movie of all nuance; the thoughtful verisimilitude that makes its middle third so invigorating is replaced by a blockheaded war of old-school versus new-school. Sully and his copilot are the calm, ruggedly individualistic voices of reason, sagely preaching the gospel of experience and expertise. By comparison, the NTSB personnel, government agents pathetically clinging to computer models and abstract hypotheses, are revealed to be callous and clueless. It’s a crude oversimplification, one unbecoming of a film that pretends to honor the virtues of hard work and honesty.

Perhaps Eastwood felt concerned that, if he did not transform the investigators into cartoonish villains, audiences would grow restless. But that’s the other issue with Sully: Strip away the NTSB’s exaggerated malice, and there just isn’t much here that’s worthy of a movie. The script throws in a few pre-flight scenes with a handful of passengers, but it’s a feeble attempt to add definition that only reinforces their uniform anonymity. We also receive two arbitrary flashbacks to Sully’s flying career, both of which could have been inserted anywhere in the narrative and which feel designed to simply pad the runtime to feature length. Even Laura Linney—no stranger to making the most of her brief time in an Eastwood film—is wasted as Sully’s wife, popping up for a few phone calls that scream “blandly supportive spouse”. Ultimately, Sully is a 90-minute movie that feels like it could have been condensed into a half-hour TV show. (Do not even attempt to compare this film to Captain Phillips, the agonizing thriller in which Hanks played another captain of a vehicle that in 2009 found itself enmeshed in a heavily publicized nightmare—the similarities end there.)

Eastwood loves heroes—so do we all. But in relentlessly bludgeoning us with Sully’s unimpeachable heroism, he somehow diminishes it. Still, I’ll try to keep perspective and label Sully an underwhelming disappointment. That sounds harsh, but it could be worse. If I were partial to Eastwood’s reductive rhetoric, I might say that, while Sully is a hero, Sully is a disgrace.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.