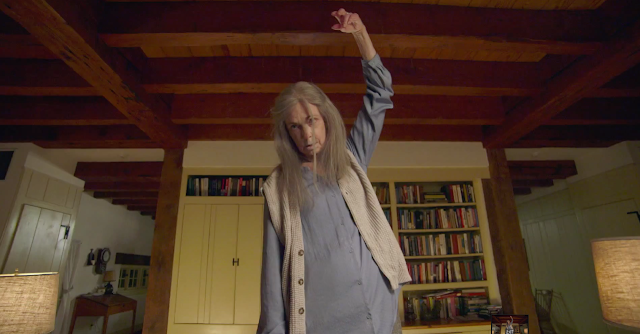

The Witch: A Puritanical Walk in the Wicked Woods

Early in The Witch, Robert Eggers’s sly and skillful horror film, a man goes hunting with his 12-year-old son. They’re searching for game in the midst of a dark, ominous wood, but they also find time for some standard-issue father-son bonding. Only it isn’t quite standard-issue; when the man, William (Ralph Ineson), cautions the boy, Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), against the dangers of sleeping too late, he solemnly intones, “The devil holds fast your eyelids.” That delectable piece of diction encapsulates The Witch‘s dual preoccupations. It’s a movie about the danger of religious fervor, but it’s also about communication—what people say (and don’t say), and, more importantly, how they say it. As the adage goes, the devil is in the dialogue.

The Witch, which takes place in the 17th century, purports to base its tale of literal and allegorical horror on actual period sources. To that end, the characters speak largely in early-modern English, which means there are a great many thous, haths, and dosts. (Even the film’s marketing materials get in on the act, treating the title’s W as consecutive V’s.) This requires a small act of translation on the part of the audience—not unlike when listening to Shakespeare, you have to actively puzzle out the characters’ speech, rather than simply absorbing it. This assumes that you can hear it; the film’s sound design picks up the rustling of branches and the bleating of animals, often compelling you to strain your ears to comprehend every flavorful morsel of colonial argot. Read More