The Manifesto is counting down every theatrical release its proprietor watched in 2013. Today, we continue with our look at the least memorable movies of 2013. If you missed Part I, you can find it here.

Moving on to the remaining movies I’ve already forgotten:

The Iceman. Richard Kuklinski purportedly killed over 100 people while working as a mob hit man. Factually speaking, that’s pretty terrifying, but in director Ariel Vromen’s eyes, it’s also worthy of a movie. Why? The reason escapes me, as The Iceman is little more than a grim, grimy exercise in repressed rage. Vromen did have the good sense (or luck) to cast Michael Shannon, a physically imposing actor in the midst of a meteoric rise—in addition to his fine work on HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, Shannon turned heads with his revelatory performance in Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter, then landed a plum part in Man of Steel—but while Shannon is a fearsome screen presence, he can provide little depth to a film that seems mesmerized by Kuklinski’s very existence. It’s as if Vromen believes that simply informing the audience that a remorseless assassin also had a family spares him from the imperative of delivering a thoughtful or compelling narrative. Throw in its linear structure and point-and-shoot style, and The Iceman is unmemorable in the most literal sense; the only scene I can remember in any detail occurs when Kuklinski permits one of his targets to pray before executing him. Otherwise, all I can recall is a smudgy streak of violent executions and shrill domestic fights, with no underlying tension or hook. (According to IMDb, James Franco, Winona Ryder, and Ray Liotta all appeared in this movie. I remain unconvinced.) Kuklinski eventually received a life sentence, which somehow seems appropriate—to toil in obscurity is just what this ugly, irrelevant movie deserves.

Jack the Giant Slayer. When viewed from a lenient perspective, Bryan Singer’s playful take on “Jack and the Beanstalk” is perfectly acceptable. It’s light and airy, with a spacious, inventive production design and a spirited score from John Ottman. Moreover, the computer-generated giants are convincing, and the medieval battle scenes, while hardly revolutionary, at least provide a respite from the gunfire and detonations that litter most summer studio productions. There are worse, less diverting times to spend at the movies. But that standard of adequacy is hardly one that Singer—the director of the first two (pretty good) X-Men movies, plus the cult hit The Usual Suspects and the underrated Valkyrie—should strive to meet. Jack the Giant Slayer may strike a refreshingly breezy chord in a marketplace dominated by glowering and destructive pictures, but it remains profoundly lazy in such rudimentary areas as plot and character. All of the human interactions in the film—the earnest romance, the strained comedy, the fiendish villainy—feel perfunctory and underwritten, as though Singer is far less interested in his characters than in the mechanics of their fight against a tribe of towering behemoths. But perhaps that’s by design: The giants are impressively rendered as foul and grotesque, but they’re less evil than irritable, and they tend to regard Jack and his ilk with a mixture of contempt and indifference. They and Singer seem to be of like mind.

Kon-Tiki. Joachim Rønning’s and Espen Sandberg’s quasi-epic—which earned an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film—tells the tale of a hardscrabble band of seafarers who crossed the Pacific Ocean on a raft in 1947. They constructed the raft from balsawood, without any modern materials, in an effort to prove that the ancient settlers of Polynesia made the very same crossing thousands of year earlier. (In 1947, this proposal apparently sounded scientifically heroic rather than just plain stupid. Also, that the voyagers used modern machinery to actually build the raft didn’t seem to violate their self-imposed rules. No matter.) That yields the promise of an exciting romp of high-seas adventure, but Rønning and Sandberg derive surprisingly little cinematic suspense from their pioneers’ maritime journey. After a boilerplate setup in which the group’s leader is shown to be fighting against an entrenched scientific establishment—a clumsy, obvious ploy for our sympathy—the movie basically involves a few men sitting on a raft, hoping that the wind propels them in the proper direction. It’s dull, dreary stuff, and after a time you begin to wish that an enemy vessel would appear, just to give our heroes something tangible to fight against. Worse, Kon-Tiki exhibits little effort to differentiate its characters; with the exception of a panicky engineer, all of the explorers are hardy, brave folk, making them a rather bland batch who hardly inspire a rooting interest. Kon-Tiki tries to make a heartfelt case for the academic value of scientific discovery, but it would prove more effective if we gave a damn about the scientists in the first place.

Mama. Reduced to its essentials, and Andy Muschietti’s vaguely supernatural thriller—about a pair of young girls who receive the protection of a spectral being, who in turn grows savagely possessive when adults interfere with her de-facto parentage—is pretty dumb. But it has its virtues, most notably the phenomenal performance of Megan Charpentier, an 11-year-old actress of extraordinary poise who, along with an admirably committed Jessica Chastain, brings a human dimension to Mama‘s cookie-cutter horror. The movie also marks Muschietti as a genuine talent with a keen eye, particularly in a gasp-worthy early sequence (in which he shrewdly bifurcates the frame) that’s downright masterful. It’s a shame, then, that Muschietti ultimately squanders his assets, ignoring the interpersonal dynamics in favor of cheap scares and ungainly backstory. Mama‘s final third is little more than a things-go-bump-in-the-night spookfest; it’s facile, haunted-house schlock transplanted to some very creepy woods. But the ending has an elegiac twist that’s almost touching, and it’s indicative of Muschietti’s potential. (He’s already been fêted by Guillermo del Toro, and Universal has reportedly tapped him to helm its reboot of The Mummy.) Mama proves to be a decidedly curious calling card for Muschietti: It both shows what he can do and suggests that he can do so much better.

Now You See Me. I have an exceedingly high tolerance level for twist-laden movies—I highly enjoyed both Wild Things and Swordfish, for example—but Now You See Me‘s narrative acrobatics exceed even my liberal threshold. Louis Leterrier’s magic-based actioner attempts to function as what Hitchcock dubbed a “Refrigerator Movie”, the kind that so engrosses you with its moment-to-moment hijinks that you can’t be bothered to notice its gaping plot holes until after it’s over (when you’ve gone to make yourself a snack). And it might have succeeded, had Leterrier’s approach not been so blankly generic. The overarching concept—a troupe of self-serving magicians wield their talents to swindle a corrupt insurer, essentially acting as white-collar vigilantes—is appealing, and in its early passages, Now You See Me is a satisfying blur of sleight-of-hand, with Leterrier’s nifty camerawork accentuating his heroes’ mystical derring-do. So why does the film resort to such numb action-movie clichés as a frantic car chase on New York City highways, or an equally rote foot chase through the streets of New Orleans? The problem isn’t just that the movie is fundamentally empty; it’s that Leterrier’s execution, while suitably workmanlike, has none of the flair or showmanship he purports to impart to his characters. Unlike a true magician, he can’t distract you from keeping your eye on the ball, meaning that as the plot twists rise, so will your eyebrows. Eventually, the sheer number of contrivances becomes too much to bear, and when Now You See Me concludes with one of those everything-is-explained flashbacks, it induces more groans than gasps. Conning insurance companies may be easy, but conning your audience is a difficult trick indeed.

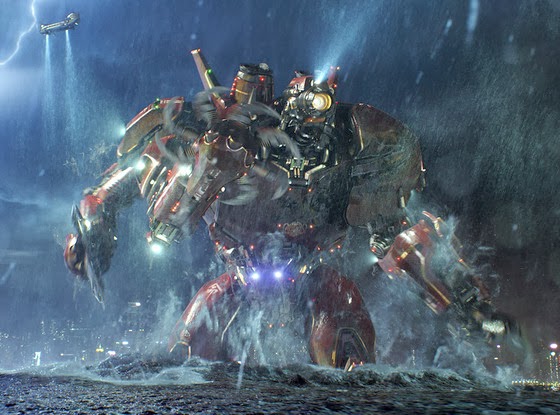

Pacific Rim. When he was young, Guillermo del Toro liked monster movies. When he grew up, he turned into a pretty talented movie-maker himself, putting a playful, anarchic spin on the Blade and Hellboy franchises while peaking with the sublime Pan’s Labyrinth. Having built himself some blockbuster cachet, it was only natural for del Toro to brandish his Hollywood currency and convince Warner Bros. to give him $190 million to make a movie about, well, giant robots fighting giant monsters. That’s pretty much all Pacific Rim entails—watching it is not dissimilar to watching an extremely spoiled child mash his technologically advanced toys against each other over and over. To the extent the film features human characters, they exist merely as vessels, stoically piloting the immense robots in battle against their Godzilla-inspired foes. Of course, del Toro wants all of this to be fun, and to his credit, Pacific Rim is impassioned without feeling labored; it’s sly homage, not outright worship. But no matter how much childlike zeal he pours into his project, del Toro can’t obfuscate the unavoidable truth: Watching two lumbering, inanimate objects endlessly slug it out feels boring, pointless, and a bit puerile. Perhaps it could have been invigorating, but del Toro’s staging of the relentless combat is dour and mechanical, with darkness often obscuring the entities’ features and making it difficult to discern which beast is clobbering which. Del Toro envisioned Pacific Rim as the apotheosis of his youthful sense of wonder, but as it turns out, some children’s fantasies are better left to the imagination.

The To Do List. Aubrey Plaza is a rare breed. In a market saturated by perky and appealing twentysomething actresses, Plaza’s calling card is hostility; her characters range from expressing jaded superiority to outright disgust. But there’s an underlying sweetness to her as well, and it suggests that her reflexive scorn is less an actual attitude than a protective mechanism. She’s more than deserving of a star vehicle, but sadly, The To Do List proves to be beneath her. The movie casts Plaza as a little-liked valedictorian with no sexual experience who resolves to educate herself before heading to college. What follows is a predictable pattern of sexual invitations, humiliations, and reconciliations that’s basically just a distaff spin on American Pie, only without the genuine affection for its characters—it’s mildly funny, slightly sweet, and completely forgettable. The only truly original moment occurs near the end, when Plaza’s character displays no regrets about her selfish behavior, instead choosing to savor her assertion of independence. Otherwise, though, The To Do List simply demonstrates that dumb and raunchy comedies are secretly solicitous and tame, and the fact that it features a woman makes it no less afraid of upending the status quo. For a movie about a supposedly adventurous girl who checks off boxes like “Dry-humping” and “Motor-boating”, The To Do List is disappointingly listless.

The Way, Way Back. Of all the mediocre movies highlighted in these two posts, The Way, Way Back is probably the best. It’s a reliably uplifting coming-of-age story, it’s largely well-acted, and it effortlessly evokes the bygone sensation of a teenager being unjustly cloistered with one’s family in a dead-end beach town. But aside from a fantastic, wonderfully casual performance from Sam Rockwell, the characters of The Way, Way Back feel strangely incomplete, as though writer-directors Nat Faxon and Jim Rash (who co-wrote The Descendants with Alexander Payne) sketched them out but forgot to color them in. Nowhere is that sense of vague uncertainty more present than in Duncan, the movie’s protagonist played with suffocating blandness by The Killing‘s Liam James. Don’t get me wrong: Normal people (and teenagers) are perfectly acceptable subjects for compelling and daring stories. But Duncan isn’t an Everyman so much as a Nothing Man—he has no real personality to speak of, and although we’re meant to sympathize with his alienation, I found myself puzzled why so many strangers would befriend this sullen, uncharismatic loner. (Naturally, he draws the interest of an attractive, conveniently single female neighbor, which suggests that the pickings in this town must be awfully slim.) What’s frustrating is that the movie features enough intriguing supporting characters—in addition to Rockwell and Allison Janney (a hoot, as ever), Steve Carell is admirably unlikable, while Toni Collette and Amanda Peet both suggest well-meaning, chronically unlucky women—that it makes you wish Faxon and Rash had discarded Duncan altogether and simply focused on the adults and their foibles. As The Way, Way Back recognizes, coming of age isn’t easy, but rooting for its hero shouldn’t be this hard.

The Wolverine. Immortality is often viewed as a curse to world-weary superheroes, but it’s even worse for filmmakers. If a hero literally can’t die, how is his director supposed to place him in any real peril? James Mangold recognizes this dilemma, and in The Wolverine, he and his screenwriters (Mark Bomback and Scott Frank) smartly devise a plot to strip the adamantium-laced nomad of his powers. The only snag is that the plot is woefully undercooked, and the characters are equally underdeveloped. Perhaps there was something involving a shape-shifting lizard-woman, and maybe an old man who morphs into a gigantic suit of armor? You’ll forgive me if I’m struggling to remember—I’ll simply refer you to the title of this post. Mangold does concoct two sterling set pieces, the first a bracing, nimbly choreographed fight atop a speeding bullet-train, the second a legitimately suspenseful sequence in which Hugh Jackman (aging as imperceptibly as his character) must perform open-heart surgery on himself. That those scenes stand out, however, merely reinforces the overwhelming sense of banality that suffuses the remainder of the film. The Wolverine features the usual litany of problems that plague modern superhero movies—thin characters; clunky dialogue; overlong, maladroit action scenes—but the flaws here seem secondary to the movie’s paralyzing indistinction. I can’t criticize it in any further detail, not because it doesn’t have its problems but because I literally can’t remember them. And in a cinematic landscape awash with rote action pictures, that is perhaps the most damning assessment a critic can give.

Coming up next: The Failures.

Previously in the Manifesto’s Review of 2013

The Unmemorables: The Least Memorable Movies of 2013 (Part I)

The Worst Movies of 2013

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.