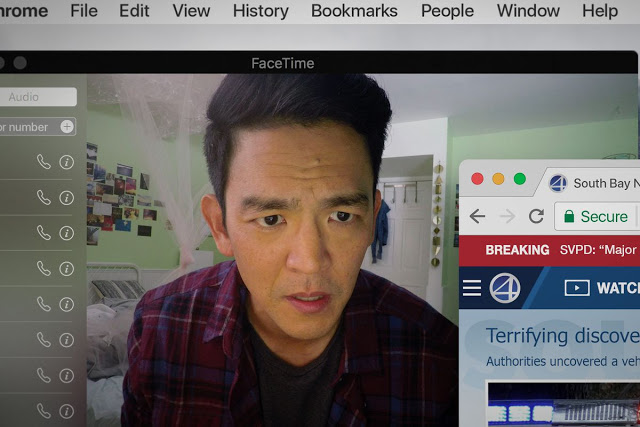

Searching: Tumbling Down the Internet Rabbit Hole

Did you know that technology is, like, A Thing? Were you aware that people regularly communicate via the internet, often in the guise of false personas? Have you ever grappled with the reality that innovations in hardware and software have, in both positive and negative ways, forever changed the contours of human interaction? If your answer to these questions is no, then you are sure to be electrified by Searching, a clever and gimmicky little thriller directed by Aneesh Chaganty. But if you have even the faintest familiarity with online culture—if you have a Gmail account or an iPhone or a web browser—you may find this film’s purported insights to be stale and preachy. Who knew the kids these days were so darned secretive?

I dare say most of us. But just as we shouldn’t judge an online account based on its avatar (whoops, spoiler alert!), we shouldn’t judge a movie for its tiresome themes alone. And Searching, despite its occasional shrillness, is a taut and engaging potboiler, as well as an audacious formal exercise. It may not have anything meaningful to say about technology, but it does use that technology in new and interesting ways. Read More