NOMINEES

Josh Brolin – Milk

Robert Downey Jr. – Tropic Thunder

Philip Seymour Hoffman – Doubt

Heath Ledger – The Dark Knight

Michael Shannon – Revolutionary Road

WILL WIN

It’s perhaps the most relevant question of the 2008 Oscars: Does anyone have a chance to beat Heath Ledger?

There are a few potential answers to this question. The most direct – also the most accurate and the most important – can be condensed to one word: no. The more pompous answer goes something along the lines of, “The only person who can beat Heath Ledger is Heath Ledger,” a line of reasoning that vaguely and counterintuitively refers to the inescapable fact that Heath Ledger is dead. This is, of course, an unfortunate fact, but also sad is that Ledger’s death has become inextricable from his actual performance. Part of this is the nature of modern American publicity, while part is tied to the unnerving creepiness of the performance itself – his character The Joker is at once a casual dispenser of death and twisted philosopher of it – but no Academy member will look at the role and see only the acting. Their judgment will be affected, to some degree, by the tragic circumstances of Ledger’s demise.

As such, it’s only fair – if perhaps a bit vulgar – to ask the question: Does this in any way damage his chances of (posthumously) winning the Oscar? (I’m less interested in whether it might help his chances – no matter the reason, he’s the frontrunner, and it’s his award to lose at this point.) The answer: not that I can see. It is possible, I suppose, that a handful of voters may develop some half-assed rationalization that the Oscars are really about celebrating the living rather than mourning the dead, or some horseshit like that (my favorite online critic, James Berardinelli, actually made that exact argument in a severely misguided column), or that the extensive media coverage surrounding Ledger’s death may have actually obscured the genius of his performance, since voters will have a harder time sifting through the haze of gossip. Still, I can’t imagine that a significant percentage of Academy voters would fall prey to such fallacious reasoning, especially not when the sympathy Ledger’s death engendered is so acute.

For their part, Warner Brothers is playing this exactly right. David Carr in the New York Times has a nice article characterizing the studio’s campaign for Ledger’s Oscar as a sort of quiet, soft-pedaled insistence. Rather than shoving promotional materials down voters’ throats and risking alienation, they’re wisely letting the performance speak for itself.

Of course, things might be more interesting if Ledger were matched up against a rival generating any semblance of buzz. He isn’t. Brolin and Hoffman have each been largely ignored to this point, with voters and studios instead focusing their attention on the more high-profile stars in their respective pictures (Sean Penn for Milk, Meryl Streep for Doubt). Few people have ever heard of Michael Shannon, and while Robert Downey Jr.’s nomination was welcome, he’s never been in serious contention.

Just to be sure, we can just look at the stats. Ledger has already been honored for his work in The Dark Night a total of 15 different times (he lost only once, to Shannon at the Satellite Awards, whatever the fuck they are). The guy has a better winning percentage than I did with the ’92 Oilers in Tecmo Bowl. Anyone picking against him at this point isn’t being sneaky or contrarian, just foolish and self-indulgent. There are few times where I can make a prediction with absolute confidence, but declaring Heath Ledger the winner for Best Supporting Actor is one of them.

SHOULD WIN

I like all of these performances, which is damning them with faint praise, as Best Supporting Actor is usually one of my favorite categories. It’s nice to see Josh Brolin recognized, even if it is a year late (he should have been nominated for his remarkable work in No Country for Old Men), but his acting in Milk didn’t overly impress me. He’s a smart actor, and in playing the despicable character of Dan White, he recognizes that it would be disastrous to either sentimentalize or radicalize him; as such, he keeps us at a distance. It’s the right move, but it doesn’t necessarily translate to a compelling screen performance. (Frankly, I liked him better as George Bush in W..)

The same goes for Philip Seymour Hoffman as a vaguely suspicious priest in Doubt. Hoffman underplays the role, often deferring to the scenery-chewing Meryl Streep (though there’s a great moment when he simply sits in Streep’s chair, silently affirming his hierarchical superiority). John Patrick Shanley’s screenplays mandates that Hoffman’s Father Flynn remain ambiguous to the audience so we can never get a confident read on him, meaning Hoffman has to accentuate his character’s overt friendliness while also supplying a subtext of creepiness. He’s generally up to the challenge, if perhaps a bit too relaxed at times, thus throwing off the balance in some of the more confrontational scenes. It’s still a perfectly acceptable performance, but it pales in comparison to the tour de force Hoffman provided in last year’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.

Robert Downey Jr., in contrast, is in peak form in his absolutely hilarious performance in Tropic Thunder. The obvious level of recursion involved – he’s a self-important American actor who’s playing a self-important Australian actor who’s playing a self-satisfied black Army captain – would be satisfying enough to generate a few yuks if any recognizable name was attached; as such, he could have mailed in his role and still won over viewers. For all his ostensible inclinations toward cynicism and laziness, however, Downey Jr. is one of the more dedicated actors working today, and despite Tropic Thunder’s standing as a comedy, he unreservedly throws himself into the part. When he barks to Ben Stiller, “I don’t drop character till I done the DVD commentary,” there’s a delectable level of ironic truth inherent in that statement, as there is in his enthusiasm when he eagerly dissects a fellow actor’s performance (“He’s breaking down the aesthetic – this is Acting 101”). It’s hardly an emotionally resonant performance (not that it should be), but it sure is a fun one.

There’s little fun to be had in Revolutionary Road, in which Michael Shannon has limited screen time, but he sure makes the most of it, fashioning perhaps the most memorable character in the film. It helps that screenwriter Justin Haythe (or perhaps novelist Richard Yates) gives him some marvelously acidic dialogue, but Shannon seizes the opportunity. With his towering frame lending him a stature that is somehow both austere and menacing, he crashes into the faux-peaceful suburban life of the movie’s protagonists, bringing with him truth, bitterness, and no shortage of loathing. While he spews plenty of that loathing at not-so-innocent bystanders, some of it is self-directed – he recognizes that he’s a part of the world he so badly despises, and he hates himself all the more for it.

Nevertheless, watching the movie, I couldn’t shake the feeling that Shannon’s role functions more as a plot device than an actual character. He’s credited as John Givings, but really he’s just The Guy Who Tells the Truth. When he delivers his speeches of vitriol, he’s really a narrative construct whose job is to strip away the veneer of contentment that blankets the characters in Revolutionary Road and reveal the emotions buried underneath – rage, desperation, and fear. This is no fault of the actor, but that Shannon’s character lacks proper dimensionality as drawn in the screenplay makes his performance somehow less meaningful.

The search for meaning in Heath Ledger’s performance in The Dark Knight is a fruitless one, as is any attempt to illuminate some sort of linkage between his role as the sadistic, death-obsessed Joker and his own untimely death. I’ve always prided myself on my ability to distance myself from actors’ and directors’ personal matters when forming an opinion of their work. When I’m watching movies by Mel Gibson or Woody Allen, I evaluate them based on their artistic merits, not the public image of their creators. So when I’m discussing Heath Ledger’s nomination as Best Supporting Actor for The Dark Knight, I don’t want to talk about whether or not his own personal demons colored his work in the picture, or if his immersion into the role of The Joker somehow influenced his own worldview. I just want to talk about his performance.

And it’s a great one. It is also highly shrewd. The natural method to playing a villain as colorful and explicitly evil as The Joker is to ham it up, scoring some cheap laughs while creating a larger-than-life caricature. (Such was Jack Nicholson’s approach in Tim Burton’s original Batman.) This technique is easy and fun, but it’s also less resonant. What makes Heath Ledger’s performance in The Dark Knight so extraordinary – and so memorable – is that his incarnation of The Joker feels creepily, insistently real. He burrows himself so deeply into the character that he never once steps outside himself and attempts to curry favor from the audience. There are no askance glances toward the camera, no sly one-liners to break the tension. There is only an unstoppable force of pure evil.

Ledger’s physical mannerisms are simultaneously grotesque and spellbinding. Constantly licking his lips as if in anticipation of his next meal, he seems to be perpetually in motion, as though he possesses too much raw energy to remain in one place for more than a fleeting moment. His voice, of course, offers no trace of his natural Australian accent, instead bubbling up from the depths of his rotting soul, and his ever-present laugh shows not the slightest hint of actual mirth. The Joker may be enjoying himself, but he never expects anyone else to join in, and that resolve – the strength not to ask the audience for their sympathy or understanding – is the single greatest asset of Ledger’s performance. He does not try to relate to us. He is simply there, and his presence generates profound terror.

Of course, I’ve been writing this is the present tense, because that’s how film criticism is written, but it’s the last time we’ll write this way about Heath Ledger. This is a sad fact, and the brilliance of his work in The Dark Knight does not compensate for the loss of a talent. But though the actor may be dead, the performance will live forever, and there’s no better way to immortalize it than to award Heath Ledger the Oscar.

DESERVING

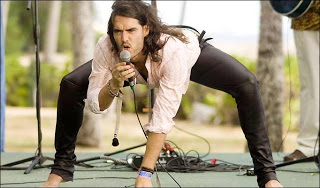

Russell Brand – Forgetting Sarah Marshall. Quite possibly the funniest performance of the entire year, Brand doesn’t just create hilarity as a preposterous British rocker – he actually brings depth and texture to the role. As for his live rendition of “Inside of You”, well, a star is born.

Bill Irwin – Rachel Getting Married. The women are receiving all the press for Rachel Getting Married, and they deserve every bit of it, but Irwin is heartbreaking as a grief-stricken father clinging to hope. He is a man of decency in a highly indecent family, and the love he displays for his daughters is touching and real.

Anil Kapoor – Slumdog Millionaire. And we thought Regis Philbin had charisma. Here’s a game-show host whose wide smile and flashing eyes are matched only by his instinct for self-promotion. After the movie, I started blurting out “It’s my fucking show!” at random intervals. I know I wasn’t the only one.

Brad Pitt – Burn After Reading. There are times when Brad Pitt decides to be serious and subtle, and then there are times when he remembers how fucking sweet he is and just lets himself go. This is the latter. “I thought you might be worried … about the security … of your shit.”

David Kross – The Reader. It’s a tall order to play a character later essayed by Ralph Fiennes and come out the winner, but Kross does so, and in his first English-language role no less. He is charged with displaying a number of Big Emotions – guilt, longing, loneliness, more guilt – but he pulls the character off without a hint of artifice. You’ll hear from him again.

Mark Strong – Body of Lies. Here’s another tall order: Star in a movie with Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe, and hold your own. As the urbane Jordanian security officer, Strong does just that, taking what could have been a stock role and creating an intelligent and strangely compelling character.

Brendan Gleeson – In Bruges. For the phenomenal scene on the phone, if nothing else. You wouldn’t think a man could bring dignity to a scene where he pretends to go to the bathroom to see if Colin Farrell just took a dump. Gleeson has that dignity.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.