I call it “December Syndrome”. It’s the strategy whereby movie studios, believing that Oscar voters have short memories, wait to release their best films until as late in the year as possible. Case in point: Of the 10 Best Picture nominees in 2010, four arrived in theatres in December, while only one (Toy Story 3) was available to the public at large prior to July. Similarly, of the past 14 Best Picture winners, eight were released in December, while only two (Gladiator and Crash) came out in the first half of the year.

It’s hard to blame studios for sticking with a pattern that works, and as long as voters keep paying homage to movies released late in the season, the months of October through December will continue to constitute a glut of cinematic glory. But the unfortunate byproduct of December Syndrome is that it turns the multiplex into a veritable wasteland for the first half of the year. If you crave high-quality entertainment prior to the summer solstice, you’d better be prepared to burrow into your Netflix account.

The months of January through April are particularly barren. Indeed, over the past eight years, of the 80 movies that have appeared on the Manifesto’s annual top 10 lists, only five (Adventureland, Duplicity, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Forgetting Sarah Marshall, and Sin City) were released prior to May in their respective years. Obviously that’s just one viewer’s subjective opinion, but I think it paints a fairly representative picture of the cinematic calendar, and it suggests a rather sober truth: Good movies just don’t come out early in the year anymore.

Or so I thought. Happily, 2011 is showing signs of reversing the trend. Not only have I already seen two excellent movies this year; I saw them on back-to-back days. Of course, this is hardly dispositive evidence – for all I know, I won’t see another good movie until the final Harry Potter film arrives in July. But this past weekend’s one-two punch of Rango and The Adjustment Bureau represents one of the best weekends I’ve had at the theatre in years. Naturally, the two films could hardly be more different, though they do share one trait: They’re both stupendously entertaining.

Rango, which is Gore Verbinski’s first feature since the third installment in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise (one of the Manifesto’s favorite trilogies, and Exhibit A of the massive gulf between my own taste and that of proper critics), is a magnificent curiosity, both agreeably familiar and wildly original. On one level, it’s a traditional western about a solitary drifter played by a movie star (Johnny Depp) who rides into a dusty town that’s rife with corruption and who must save the citizenry from seemingly certain doom. On another level, it’s an animated movie about a lizard with theatrical aspirations who receives a vision quest from a nearly-severed armadillo and whose travails are narrated by a mariachi quartet who just happen to be owls. So it’s safe to say you’ve never seen anything like Rango, even if you’ve seen it a hundred times before.

Part of the fun of Rango – and the movie, much like Verbinski’s Pirates films, provides just so much fun – lies in its gleeful homage to the classic westerns of yesteryear. In creating the aptly named town of Dirt, the art department concocts a landscape of dust, drought, and tumbleweeds, while the saloons are so shadowy and menacing that you half-expect to walk into a gunfight between Lee Marvin and John Wayne. The plot, in which nefarious evildoers have drained the town of its water supply, instantly recalls Chinatown, while Rango invariably finds himself partaking in gun duels in the sun. Depp’s drug-addled character from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas makes a sudden appearance, while Clint Eastwood’s archetypal gunslinger from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (voiced flavorfully by Timothy Olyphant) drops in for a rueful cameo, poncho and all (in a coy postmodern touch, he’s even referred to as “the man with no name”).

Having more fun than anyone is composer Hans Zimmer, who, fresh off soundtracking the dream worlds of Inception, delivers an aural pastiche that pays obvious tribute to the timeless spaghetti scores of Ennio Morricone. Zimmer is best known for his brawny, electronic-infused scores on movies such as The Dark Knight, but his work on Rango is entirely classical, if jovial. He has the gall to ape the famous “Rise of the Valkyries” sequence from Apocalypse Now, only replacing the brassy trumpets with a banjo, while his main theme features a lilting flute. It’s some of the most innovative and colorful work in his storied career.

But apart from its sly send-ups of past films, Rango has virtues all its own, most notably in its wacky, off-kilter personality. The voice work is strong, especially Depp, who showcases the same offbeat sensibility he brought to Capt. Jack Sparrow, along with Bill Nighy as the malevolent Rattlesnake Jake, a venomous villain whose rattle doubles as a machine gun. John Logan’s dialogue is full of delightful non sequiturs (“Irrelevant! Obfuscation.”), with the owls serving as a demented Greek chorus. (My personal favorite: “And so the stranger basks in the adulation of his new friends, sinking deeper into the guacamole of his own deception.”)

Visually, the movie is resplendent. The first animated film from George Lucas’ Industrial Lights and Magic, Rango is dazzlingly bright but also grimy and gritty, as befits its western locale. The textures are beautifully detailed, from the title character’s scaly skin to the dust motes that clutter the frontier. Moreover, Verbinski brings a maestro’s discipline to his action sequences, which are energetic but not disorienting, meaning we can actually comprehend who’s going where.

Rango isn’t perfect. The ultimate resolution is a bit ordinary for a film of such sparkling verve, and the romance between Rango and his designated love interest never quite pops. But those are quibbles. When a film treats its audience to a shot such as the one below – an image that encapsulates the epic sweep of an entire genre that also happens to feature a lizard riding a chicken – we’re hard-pressed not to bask in the glory of the sunset.

The Adjustment Bureau carries a whiff of Rango‘s gung-ho spirit, though it channels that energy in markedly different ways. On the surface, it’s a dystopian metaphysical thriller about a man fighting against his own fate. The forces working against him are, quite literally, the agents of God, and the film addresses such weighty philosophical topics as predestination vs. free will and the fundamental flaws of humanity. It’s a high-concept picture that occasionally seems as though it was scripted by a devotee of 2001: A Space Odyssey who did a bit too much LSD.

Yet the best and most important scene in The Adjustment Bureau is entirely bereft of any element of science-fiction, philosophy, or even action. It takes place in a hotel bathroom and involves an ordinary, mundane conversation between a man and a woman. Or it would be mundane, were it not for the crackling chemistry between Matt Damon and Emily Blunt, who play David and Elise, the two lovers at the epicenter of the movie’s vertiginous spiral. It’s a simple meet-cute – he’s practicing his speech in the men’s room, where she’s hiding from security – that transforms into an exhilarating patter between two intelligent, sexually hungry people who are irresistibly and forever drawn to each other. There’s just one problem: God doesn’t approve.

The reason The Adjustment Bureau works so well is that it anchors its metaphysical goofiness in the problems and feelings of very real people. The basic thrust of the movie is that David, upon falling in love with Elise, learns that powerful forces are determined to keep them apart, only he refuses to acquiesce – that is, he is simply incapable of giving up on his true love. Accordingly, the success of the entire film hinges on that opening scene. If we are honestly to believe that David would do everything in his power (and a few things beyond his power) to reunite with Elise, then the bond that forms between them must be both pure and visceral.

And Damon and Blunt play it perfectly. In both the initial meet-cute and a chance encounter (or is it?) on a bus shortly thereafter, they instantaneously exude lust, longing, and actual love. It helps that they’re both spectacularly good-looking; in our minds, keeping such bastions of beauty apart would be nothing short of sinful. But it’s more about the electricity that surrounds them. George Nolfi’s dialogue buffets the characters’ words back and forth like a fencing match, and the actors seize on the dialogue. David, a young and already jaded politician, can sense the presence of authenticity, and Damon plays this recognition with baffled, awestruck wonder. Blunt, for her part, is an absolute firecracker, commanding her foil’s attention with the slightest lean of her lithe body. Watching them, we recognize that they’re meant to be together.

Except, of course, they’re not. David quickly finds himself face-to-face with an army of “case officers” clad in monochrome suits and clutching books that seem to be continually writing themselves. Their affiliation is ambiguous, but their powers are unassailable, and their message is equally clear: Stay away from Elise.

What follows is a dizzying series of improbable events, buttressed by some philosophical ruminations on world history and the nature of man. All of this is preposterous; it is also tremendous fun. You can’t put a price on the exchange between David and a particularly severe adjuster named Thompson (an effective Terence Stamp), when David wonders what happened to free will, and Thompson replies, “We tried free will. Didn’t work.”.

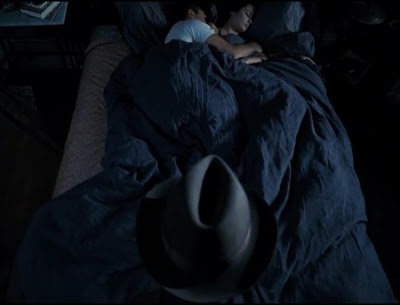

Yet I don’t mean to imply that I’m mocking The Adjustment Bureau. It is, to its great credit, a movie about big ideas, and it approaches those ideas with a seriousness that’s generally anathema to the multiplex. Nolfi, adapting a short story by sci-fi legend Philip K. Dick and also making his directorial debut, shows an ability to ask probing, academic questions while constantly pushing the pace and upping the stakes. He also expresses his ideas visually, such as in a magnificent shot in which the camera lingers on two lovers sprawled on a bed in apparent bliss, then pans down to reveal a figure watching over them with questionable intentions.

Casting is crucial in any movie that stakes its success on romantic chemistry, and The Adjustment Bureau gets it right. Damon served as the ideal Jason Bourne because he could be both intense and oddly blank, and that latter quality informs his character’s cynicism toward politics; it also allows him to bounce from playing the sleepwalking, speechifying candidate to the earnest, smitten champion. Blunt has the more challenging role because she’s required to exude exasperation and confusion as well as emotion, and she nails it – the fear on Elise’s face when her world is suddenly turned upside-down is hauntingly real. Meanwhile, John Slattery slips into the well-oiled shoes of a high-level adjuster with supreme ease.

For a movie that takes as many nervy chances as The Adjustment Bureau does, it’s unsurprising that not all of them work. The final voiceover is far too on-the-nose and should have been excised, while some of the plot contortions feel forced. But perhaps that sense of narrative suddenness is only fitting in a film that has the temerity to suggest – with a straight face, no less – that we’re all moving along some preordained path that can be continuously adjusted.

Walking out of the theatre, I gushed to my father how much I enjoyed the movie, and he stoically replied, “Well, you’re a romantic”. Indeed I am, and a hopeless one at that. My three favorite films of the past decade were Atonement (a love story between an aristocrat and her gardener), Spider-Man 2 (a love story between a superhero and the girl next door), and Wall-E (a love story between two robots who can’t talk). There’s something singularly satisfying about watching a movie that properly captures the giddiness of falling in love and the desperation of losing that feeling. The Adjustment Bureau, for all its metaphysical ambitions and penetrating societal insights, is at its heart about the existence of love and its transcendent value. It’s about a simple, cockamamie belief that’s so crazy it has to be true: Love can change the world.

And that was my weekend at the movies. I never imagined I’d say this, but if the rest of 2011 can keep pace with the first weekend in March, it’s going to be an awfully good year.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

"Aural pastiche"?? Who ARE you?

I definitely will be seeing these movies. Maybe even in a theater. Thanks, Beckler.

I just Googled "aural pastiche" to see if the Manifesto would pop up as the top hit. Turns out 14 websites outrank me, and there are 1,520 total hits. So much for inventing a literary term of art.