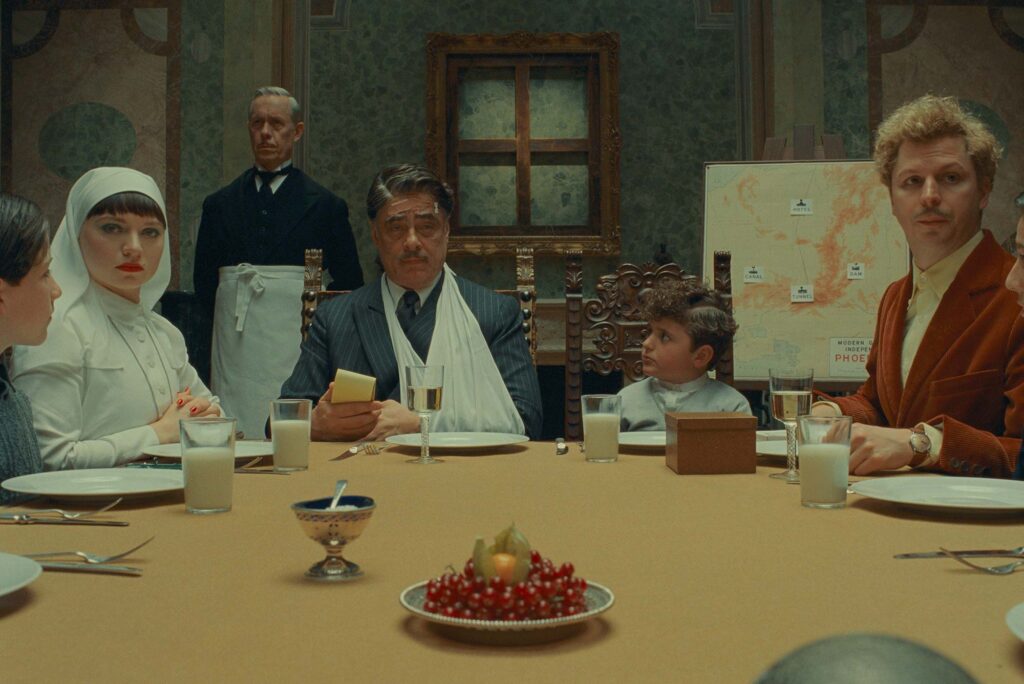

Wes Anderson’s movies are so meticulously constructed, it’s easy to overlook that they also tend to be explosive, messy, and violent. It takes all of 30 seconds into The Phoenician Scheme, his latest lavishly imagined whirligig, before someone gets literally blown in half by a missile. Not long after, the picture’s unscrupulous hero, an entrepreneur named Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro), emerges from the wreckage of a plane crash, trying to stuff a protruding organ back inside his body. Over the picaresque adventure that follows, Korda will face flaming arrows, gun-toting guerillas, duplicitous spies, overcooked pigeons, and a pit of quicksand. He’s the unflappable eye of a fastidiously unstable hurricane.

That all of this mayhem unfolds in the context of Anderson’s characteristic rigor—a method of careful framing, crisp camerawork, and filigreed production design—isn’t really a product of dissonance. Rather, The Phoenician Scheme harmonizes control and commotion. Anderson’s style is often pejoratively deemed fussy, but his exacting craft doesn’t drain the life from his filmmaking. Quite the opposite: The rich colors, the sharp wordplay, and the impeccable ornamentation all coalesce to imbue the proceedings with urgency and vivacity. In this heightened alternate reality, precision generates momentum.

The same could be said about virtually all of Anderson’s pictures, and his newest labor is somewhat less ambitious and provocative than his other recent works. There is no nesting-doll structure (as in The Grand Budapest Hotel), no fluidly shifting POV (as in The French Dispatch), no trenchant interrogation of his own artistry (as in Asteroid City). But comparison is the thief of joy, and if The Phoenician Scheme is less knotty than is typical for Anderson, it also happens to be one of the most purely pleasurable movies he’s ever made.

Part of this derives from the screenplay, which is both delightful and inscrutable. Korda’s titular plan involves the weaponization of famine, the use of slave labor, and the collaboration of investors, all in the effort to achieve… something. The particular details of the scheme are never explained. Korda frequently discusses “the gap,” which he clarifies (I use the word loosely) refers to both a budget shortfall—tidy graphics periodically appear on screen, tabulating the percentage of funds pledged by various financiers—and a more existential fissure. The brunt of the story follows Korda as he travels across a lightly fictionalized Europe and North Africa, striving to convince friends, enemies, and relatives to support his industrial aspirations.

This means that each of The Phoenician Scheme’s chapters—which are compartmentalized into actual shoeboxes and other apparel repositories, a charming and distinctly Andersonian quirk—transpires according to roughly the same pattern. And in fact, repetition is one of Anderson’s most reliable and engaging weapons. “Myself, I feel very safe,” Korda says time and again as his private flights are imperiled by leaky equipment and would-be assassins. His business negotiations, which begin with erudite dialogue, invariably degrade into unintelligible shouting matches, recalling the intermittent animalistic savagery of Fantastic Mr. Fox. And he routinely greets new arrivals with the pleasantry, “Help yourself to a hand grenade.” These flashes of recurrence leaven the absurdity with warmth and humor.

But while The Phoenician Scheme is a very funny movie, it isn’t entirely a laughing matter. Arrayed against Korda, besides his untrustworthy half-brother Nubar (played with a bushy beard and a snarl by Benedict Cumberbatch), is a cadre of bureaucrats, led with officious zeal by an operative called Excalibur (Rupert Friend). Outfitted in dark grey suits and seated around a semicircular wood-paneled table, these executives conspire to disrupt Korda’s plans, manipulating the markets for specific commodities—at one point, there is an elaborate digression regarding rivets—and also engaging in espionage.

Korda, with his abiding narcissism and his squishy morals, is nobody’s conventional idea of a hero. But he is an artist, a visionary, and his creative spirit renders him the opposite of Excalibur’s unmerry band of G-men who embody the movie’s true villains, even more so than Nubar’s red-blooded brutality. And even as the Phoenician Scheme, which was shot in the not-quite-Academy aspect ratio of 1.5:1, steamrolls forward as a fizzy and buoyant caper, it also develops a parallel track involving the battle for Korda’s immortal soul.

There are plenty of other souls on board. As usual, Anderson has stocked his film with small roles played by big-name actors, some of whom pop more than others. Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston are marvelous company as a pair of basketball-savvy brothers (one attended Pepperdine, the other Stanford), while Riz Ahmed (as an Arabian prince) and Mathieu Amalric (as a nightclub owner) fit snugly. Less appealing are Richard Ayoade (as a freedom fighter) and an oddly hammy Jeffrey Wright; for her part, Scarlett Johansson doesn’t have much to do. Michael Cera, in contrast, busies himself aggressively as Korda’s administrative secretary, deploying a happily ridiculous European accent that defines his bookish demeanor as much as his tweedy attire.

Yet the most important player in The Phoenician Scheme, aside from Del Toro, is one I’d never heard of before. Her name is Mia Threapleton, and she plays Liesl, Korda’s only daughter (he also has at least eight younger sons who tend to sit in the balcony and fire munitions at their father). Casting a relative newcomer made sense (Anderson had apparently never heard of her either; turns out she’s Kate Winslet’s daughter), given that Liesl has long been estranged from Korda and isn’t a member of his club, with its vast old-boys’ network and backroom dealings. But there is nothing tentative about Threapleton’s performance. She exhibits a coiled physicality, and she delivers Anderson’s verbal volleys with clockwork timing, helping to lend the movie’s many dialogue exchanges a steady rhythm. She also brings out the best in Del Toro, a gifted but mercurial actor who sometimes glides through his roles; here he’s locked in, shading Korda with a latent vulnerability while still emphasizing his self-important grandeur.

Liesl, as it happens, is a prospective nun, and her chastity makes her both a counterpoint to her father’s voracious appetites and an avenue for potential corruption. The narrative of The Phoenician Scheme is relatively linear, but it occasionally departs to the celestial plane, where religious figures (including those played by Bill Murray and Willem Dafoe) debate Korda’s heavenly credentials. These passages, which ditch the movie’s vivid pastel color scheme in favor of handsome black-and-white, aren’t all that interesting in themselves. But they do coat the film in an additional layer of meaning, paying tribute to what you might call the spirituality of family. Korda doesn’t need to acquire monopolistic power or revolutionize the global economy; he just needs his daughter.

Perhaps that’s hokey, but there is too much verbal whimsy and aesthetic wonder on display for me to care. Late in The Phoenician Scheme, Korda stands before a complex diorama, one complete with model trains and flowing waterfalls. It’s almost too fine a metaphor for Anderson’s art—oh look, here’s a flamboyant innovator parading his immaculately designed vision to the broader world—but there’s real human feeling behind all of that whirring circuitry, the kind that revitalizes your faith in original cinema. Maybe Wes Anderson’s punctilious technique and restless imagination aren’t for you. Myself, I feel very safe.

Grade: A-

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.