The greatest advantage of being an amateur movie critic rather than a professional is simple: I’m not forced to see movies that I don’t actually want to see. True, I dutifully attempt to see every movie nominated for an Oscar, which occasionally induces a sense of obligation (did I really Netflix a French animated film called A Cat in Paris?), but for the most part, I watch movies because I want to, not because I’m paid to. So, until the Mr. Provis of the technology generation bestows the Manifesto with his generosity and turns this wee blog into a for-profit enterprise (note to silent benefactors: I’m still available), I can continue to avoid the truly execrable pictures that litter the multiplex each year.

As a result, I can’t possibly pretend to author a list of the actual worst movies of 2013, as I exercised my discretion and passed on such supposed fiascos as The Big Wedding, Grown Ups 2, and Movie 43. I can, however, denigrate the small sampling of this year’s films that I actively disliked. Given my selectivity, it’s a predictably short list: As of this writing, I’ve seen 85 theatrical releases in 2013, and I only found the following eight to be genuinely contemptible. There’s assuredly more dross out there, but for now, you’ll have to settle for me warning you away from these wretched offerings. In no particular order:

Man of Steel. One popular (if anti-populist) narrative concerning the state of contemporary cinema is that movies just aren’t as good as they used to be. That’s utter rubbish, but Zack Snyder’s ponderous Superman reboot will hardly quell the senseless clamor. In empirical terms, Man of Steel isn’t all that terrible; the special effects are undeniably impressive, the production design is sleek and well-conceived, and the acting is perfectly adequate. But all of that is drowned out by Snyder’s thuddingly tone-deaf sensibility, one that equates noise and explosions with verve and excitement while mistaking turgidity for solemnity. The film’s second half—in which Superman hurtles into countless buildings and terrifies a multitude of innocent pedestrians—is an agonizing slog of unrelenting sound and fury. Leaden, humorless, and utterly devoid of character development or thematic nuance, Man of Steel is a toxic exemplar of how a $225 million budget, when attached to a tattered screenplay and a creatively bankrupt director, buys absolutely nothing.

A Good Day to Die Hard. What a waste. Man of Steel may have been a monumental failure, but at least it was a failure of ambition. The only ambition of A Good Day to Die Hard—the fifth installment of the now-festering franchise—appears to have been to sell a handful of tickets in Russia, where the film’s action predominantly takes place. (The movie racked up 78% of its $305 million worldwide gross at the international box office, the third-highest such share among major U.S. releases, behind only Escape Plan and The Smurfs 2. Apparently, foreign audiences have yet to tire of 1980s action heroes and cartoons.) I’m hardly an obsessive disciple of the Die Hard series, but regardless of your level of affection for John McClane, his latest travails exhibit a weary, wheezing quality that’s downright dispiriting. The action scenes are limp and unimaginative, the villains are rote and unmemorable, and the perfunctory attempt at character-building—in which McClane attempts to reconnect with one of his children—feels reheated from the prior episode, Live Free or Die Hard. For his part, Bruce Willis looks both bored and indestructible, perhaps because no one would dare touch him as he strolls his way through the wreckage to collect a paycheck.

The Company You Keep. Robert Redford’s would-be-thriller has the skeleton of an interesting movie, one in which a seemingly decent man faces a reckoning courtesy of his past sins. But after an intriguing first reel, the movie sputters and stalls, failing both as a suspense picture and as a portrait of loss and regret. Part of that is due to Redford’s own hubris: He cast himself as the lead, but at 77 years old, he looks as though he can barely climb a flight of stairs, much less outsprint a nationwide manhunt. And while he still holds the cachet to fill out his roster with an exceptionally talented cast (Susan Sarandon, Nick Nolte, Chris Cooper, and Richard Jenkins are just a few of the high-profile names on hand), he gives them precious little to do. Oddly, the movie’s lone memorable moment occurs when an intrepid reporter (a reliably scrappy Shia LaBeouf) attempts to pick up a university student (the up-and-coming Brit Marling). It’s a scene of seeming improvisation that infuses The Company You Keep with a spark of energy. But that spark is quickly extinguished, and all that remains is a jumble of aged movie stars, looking confused about why they’re here and frustrated that they missed their nap.

Only God Forgives. Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive was one of my favorite films of 2011, a virtuosic reimagining of 1980s macho action movies filtered through the new millennium’s more refined aesthetic. For his follow-up, Refn borrows a number of Drive‘s memorable elements—extreme violence, lush photography, Ryan Gosling—and grafts them onto a narrative so stupendously idiotic that it’s hard to believe it even exists. Set in Thailand, the purported plot pits Gosling (who sleepwalks through a role that’s wholly devoid of personality) against a samurai-wielding detective who moonlights as a karaoke performer. That may sound alluring, but Only God Forgives is really just a loose, incoherent assemblage of grotesque executions, none of which is staged with any particular visual wit or élan. Not only is the movie loudly and profoundly stupid; worse, it’s tedious. Kristin Scott Thomas provides a welcome jolt as Gosling’s ferocious mother, but even she can’t rescue Only God Forgives from Refn’s flagrant self-indulgence. Perhaps Refn felt uncomfortable in the wake of Drive‘s critical acclaim and felt the need to reestablish himself as a maverick rather than a director who connects with mainstream audiences. For my part, I liked him better when he was making good movies rather than terrible ones.

At Any Price. The motivations behind At Any Price—in which Ramin Bahrani attempts to tell a sweeping tale of the plight facing the middle-American farmer in the technology age—may be honorable, but intentions can only get you so far, and Bahrani’s ambition outstrips his execution. Whereas his prior feature, Goodbye Solo, was a thoughtful and intimate affair, At Any Price is bulky and sprawling, a character study of desperation that clumsily transitions into flailing melodrama. There’s also a struggle between a tradition-minded patriarch (Dennis Quaid, very good) and his Nascar-obsessed son (Zac Efron, pretty bad); as with the rest of the film, this exploration of father-son conflict is far more compelling in theory than reality. (As an indication of the movie’s slapdash approach to storytelling, Heather Graham shows up to sleep with both men, for no better reason than that it causes strife between the two.) At Any Price scores points for effort, but it’s nonetheless a confused, muddled film that never finds sure footing. Middle America deserved better.

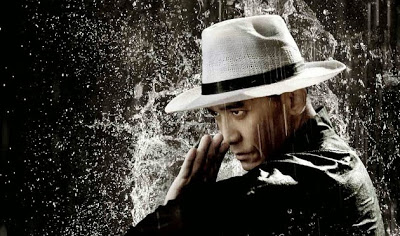

The Grandmaster. There’s a certain appeal to a legendary filmmaker like Wong Kar Wai helming a kung-fu picture: the possibility of a fertile crossbreed between high-art cinema and pulpy entertainment. Sadly, The Grandmaster is a dull, sodden film that satisfies as neither art nor pulp. Wong is a supremely elegant stylist, but his fight scenes are strangely lacking in beauty, not to mention energy. He predictably takes a philosophical approach to martial arts, but Zhang Yimou charted similar territory to far superior effect in Hero and House of Flying Daggers, which managed to be cinematically stimulating as well as piously reverent. The story, meanwhile, is completely threadbare, a familiar, languorous tale of unfulfilled love that’s populated by stock archetypes rather than actual characters. It’s as if Wong couldn’t be bothered to invest his movie with any identity, instead simply relying on his visual gifts to elevate a meandering screenplay. In this, Wong disrespects the discipline he attempts to honor.

Gangster Squad. Good actors can only take a bad movie so far. No 2013 film exemplified this axiom more than Gangster Squad (though The Company You Keep came close), an ugly, pointless Untouchables wannabe that feels as though it was scripted by a violence-crazed teenager. The crack cast—which includes Josh Brolin, Ryan Gosling, Emma Stone, Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, and Anthony Mackie—is a mighty collection of Hollywood talent, but director Ruben Fleischer seems completely disinterested in utilizing their abilities. (Gosling, by the way, could stand to be a bit more choosy; after appearing in three of 2011’s best films, he landed in two of this year’s worst.) That’s because Gangster Squad is really just a moronic revenge fable, one in which every character is either deeply noble or repulsively rotten. It can’t even qualify as dumb fun, as Fleischer’s Tommy-gun shootouts are as clunky and monotonous as Snyder’s superhero battles in Man of Steel (if blessedly shorter). In fact, the only memorable thing about Gangster Squad is that it serves as a cautionary tale: The next time you consider seeing a movie based on its cast, research the director and screenwriter first.

Prince Avalanche. It’s interesting to note that, with the exception of The Grandmaster, the preceding pictures on this list met with scorn from most critics. That’s not the case with David Gordon Green’s Prince Avalanche, which currently sits at 84% on Rotten Tomatoes (The Grandmaster is at 75%), suggesting that it’s legitimately well-liked rather than merely tolerated. I remain baffled by the insistent praise for the film, in which Paul Rudd and Emile Hirsch play a couple of nobodies tasked with hammering signage into a stretch of burned-out road. That’s it. That’s the movie. Green seems content to just let his two leads wander around in the wilderness, drinking and bickering and occasionally bonding, but really doing nothing in particular. Now, I generally don’t demand intricate plots from movies, but I do require some sort of hook, whether it’s memorable characters, snappy dialogue, evocative imagery—something. There’s simply nothing compelling about the experience of watching Prince Avalanche. It’s a boring movie about two boring people who do boring things. That it’s set amidst the aftermath of a forest fire doesn’t transform it into a profound commentary on the mundanity of everyday existence or the cyclical nature of life. It just makes us wish these two losers would hurry up and get on with their lives, so that we can get on with ours.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.