About a year ago, film critic Scott Tobias wrote a piece called “The ‘Gentleman’s F’ and the Scourge of Deliberate Mediocrity”. His thesis was that “bad movies are better than useless ones”, and while I don’t necessarily agree with his specific examples, I can see his overarching point. Bad movies may be horribly executed, but at least they’re distinctive and, in their own way, defiantly memorable. Useless movies, on the other hand, are bland, slothful, and scrupulously inoffensive. They’re rarely bad enough to induce anger, but neither are they good enough to inspire debate. They are simply consumed and then discarded, and to the extent that I remember them, it’s with the wistful knowledge that in watching them, I basically wasted two hours of my life.

And so, the following collective represents 2013’s Unmemorables: the Manifesto’s view of the least memorable movies of the year. None of these films is truly terrible—a few are even mildly enjoyable, at least in part—but they produced nothing in the way of an emotional response, be it love or loathing. I simply watched them, and then I forgot about them. And such ambivalence is, in its own quiet way, a more damning reaction than outright rage.

So here’s to the cinematic sinners who sinned by not trying. In alphabetical order:

About Time. There’s no rule that time-travel must exist exclusively within the action genre, and indeed, incorporating science-fiction conceits into the more prosaic world of romantic comedy is rife with possibility. (See also: Paris, Midnight in.) Sadly, Richard Curtis seems convinced that the mere introduction of time-travel into his otherwise lifeless romance can compensate for the film’s considerable flaws, most notably a blandness of character. There is simply nothing interesting about Tim, the temporally gifted protagonist, played by Domhnall Gleeson as a nice-enough guy with no discernible personality. Even less interesting is Mary, Tim’s supposed soul mate (played by a reliably appealing, somewhat vacant Rachel McAdams), who is sweet, pretty, and frightfully dull. The same can be said of the movie, which takes a single running joke—Tim repeatedly puts his foot in his mouth and then must use his powers to correct these minor transgressions—and quickly drains it of its comedic potential. Like most Curtis pictures, About Time has its pleasant moments (especially a meet-cute that takes place in total darkness), and Bill Nighy’s presence is always delightful. But on the whole, there’s just nothing here worth remembering, much less traveling through time for.

Admission. Tina Fey and Paul Rudd are both highly likable actors, and there’s nothing objectionable about just putting them in the same frame and letting them play off each other. But beyond that, Admission, Chris Weitz’s half-comedy, half-whatever, has no apparent purpose or identity. Or perhaps it has too many. Is it a comedy about two mismatched, flawed adults who learn to appreciate each other? A drama about the costs and the joys of motherhood? A scathing indictment of collegiate institutions and their seemingly arbitrary criteria? Admission feints at becoming all of these things but ends up being none of them, and its evident confusion is less a failure of outsized ambition than one of tentative uncertainty. In one scene, a handful of admission officers debate applicants’ credentials, and it’s clear they’re looking for something unique; getting in, it appears, is all about standing out. The movie should have taken its own advice.

The Croods. Over at The Dissolve, Tasha Robinson summed up the contemporary state of cinematic animation as follows: “As long as it’s all aimed first and foremost at kids, it can only go so far in terms of ambition, narrative complexity, serious subjects, and serious diversity.” The Croods illustrates this point all too neatly. Visually, the movie shrewdly exploits the promise of the medium, as it features several exciting, sharply choreographed action sequences that would simply be impossible to stage in the real world. But as busy as the film appears to be on its surface, it is ultimately empty in terms of its narrative. The quest story is shopworn, the jokes are easy and stale, and the themes of embracing family and self-discovery are tired and familiar. Part of my discontent may stem from my own stubbornness—”Relax, it’s just a kids’ movie,” the refrain goes—but I refuse to concede that animation exists exclusively to serve small children by delivering bright colors and lazy stories. There’s too much potential in animation to waste it on movies like The Croods that elevate gee-whiz style over actual substance.

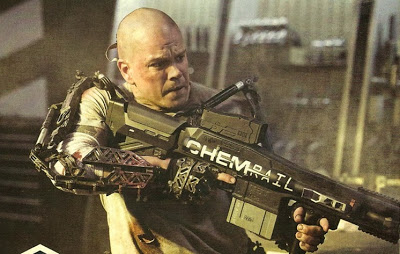

Elysium. I didn’t particularly care for any of the movies ignominiously highlighted in this post, but Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium is the only one that truly disappointed me. That’s because Blomkamp’s District 9 was a tantalizing feature debut; it wasn’t a perfect movie, but it was nevertheless an audacious, self-assured allegory that boldly fused multiple genres, including docudrama, body horror, and guerrilla action. So it’s almost crushing that Elysium plays things so safe, abandoning District 9‘s distinctly personal flavor and replacing it with by-the-book blockbuster fare. The story jabs at social metaphor, but it’s too bluntly didactic to possess any real weight, and besides, Blomkamp seems far less interested in rounding out his characters than in wielding his $115 million budget. That extra capital allowed him to hire some top-flight actors, including Matt Damon (steady as ever) and Jodie Foster (supplying the worst performance of her career), though Sharlto Copley—completely unrecognizable from the harried bureaucrat he brilliantly essayed in District 9—steals the show with a deliriously over-the-top performance as a crazed assassin. But the bloated budget really shows up in Elysium‘s action scenes, which are loud, long, and distressingly generic, as though Blomkamp consciously prioritized sheer magnitude over clarity and ingenuity. Given that he made District 9 on the (relative) cheap, it’s perhaps understandable that Blomkamp is so enraptured with all of his new toys, but next time he’d be better served using the cash to buy himself some new ideas.

Ender’s Game. There isn’t much wrong with Ender’s Game, Gavin Hood’s streamlined, workmanlike adaptation of Orson Scott Card’s wildly popular novel (which, I should disclose, I’ve never read). It has a sleek look that befits its futuristic setting, and it astutely captures the attendant burdens of isolation and ostracism that plague especially gifted children. The problem is one of scale. Ender’s Game works suitably well as a coming-of-age story, but it’s pitched as a war for humanity’s very survival. That requires it to possess a certain gravitas, but it’s difficult for the film to achieve serious resonance when it basically centers on a young boy trying to make friends while playing games in Space Camp. The stakes just don’t feel all that high, and the allegory—which vaguely attacks the notion of might-is-right militarism—comes across as both misplaced and distorted. (Politically, the movie is a muddle, doubtless the consequence of condensing Card’s book to feature-length.) And while the initial training sequences are pleasant and effective, the latter battle scenes—in which Ender barks incomprehensible commands to his posse of child soldiers while perched on a dais—play like a sound-and-light show at your local planetarium. As Ender’s Game recognizes, growing up is hard enough; must every movie teenager these days need to save the world?

Epic. See: Croods, The. But seriously, Epic is both better and worse than the other animated title in this post. Better, because the animation on display here is stunningly gorgeous, from the shimmering movements of a hummingbird’s wings to the micro-texture of each blade of grass. The movie also ostensibly creates its own universe, resulting in a rare, fresh breath of originality. Or it would, if that universe weren’t so patently purloined from other superior pictures. Epic‘s story—in which a disenchanted girl is miniaturized and must become the savior of a class of nature-warriors whose existence she has always doubted—treads such a well-worn path that you can practically see the signposts forecasting each bend in the narrative. It’s Ferngully meets Avatar, with a dash of Pocahontas thrown in. That might have been acceptable if the movie featured lively action or sharp writing, but the action (unlike that of The Croods) is merely passable, while the dialogue drifts between unmemorable and risible. There’s plenty to look at in Epic, but it would be nice if there were actually something to see.

The Fifth Estate. Bill Condon’s humdrum examination of the WikiLeaks scandal hardly deserved to become the biggest commercial flop of the year, though according to Forbes, that’s exactly what it was. It features solid-to-excellent acting from its impressive cast (most notably the chameleonic Benedict Cumberbatch as Julian Assange), and it asks some thoughtful questions about the role of the journalist in an era where speed and technological knowhow tend to trump research and patience. But Condon attempts to frame the proceedings as a new-age thriller, which is problematic because The Fifth Estate is utterly lacking in urgency or excitement. It isn’t Condon’s fault that the process of bespectacled men typing furiously on laptops doesn’t naturally lend itself to cinema, but he nevertheless fails spectacularly in his efforts to tart up the digital world, which he stupefyingly renders as a “newsroom in the sky”. (A climactic sequence, in which Condon portrays two men hacking a network by showing them literally swinging axes into bulky servers, is particularly laughable.) It’s a baffling, obtuse approach that undercuts the movie’s stabs at significance, and it betrays Condon’s ignorance of an axiom familiar to the most amateur of programmers: When solving a problem, finesse and elegance are often more effective than brute force.

42. Brian Helgeland’s sturdy, straightforward biopic of Jackie Robinson tells the story of a tremendously talented athlete who overcame the vile forces of bigotry and entrenchment in order to fulfill his dream of playing in the major leagues. In other words, it tells us nothing we didn’t already know. Robinson is an American hero with a hard-won legacy, but there’s no real insight here, and certainly no greater sense of the actual man behind the legend. The movie only really comes to life when Robinson attacks opposing defenses on the base paths; the scenes of him measuring a pitcher’s windup and taking his lead have a refreshing, immediate specificity, as though we’re witnessing an artisan honing his craft. Otherwise, however, Helgeland treats Robinson as a mere cipher in his polemical study of hatred and courage, and his conclusions—that racism is bad, and that it can be thwarted through endurance and camaraderie—are worthy of a social studies textbook. As a result, 42 is pious and forthright rather than nuanced and exploratory; it’s admirably educational, but hardly inspirational.

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug. I was a half-hearted defender of An Expected Journey, the opening chapter of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy. Yes, it’s too long, and some of the subplots feel hopelessly arbitrary (Radagast the What?), but it’s breathtakingly well-made, and there’s a real sense of passion to the project. But my enthusiasm has begun to wane with the second installment, which deemphasizes story in favor of elaborate, repetitive fight sequences. To be fair, Jackson remains one of the preeminent action directors around, and several of the movie’s early set pieces—including a terrifying encounter with monstrous spiders (a return to Jackson’s horror roots) and a magnificent river chase in which the protagonists travel helplessly by barrel—are marvels of clear-eyed, energetic filmmaking. But as The Desolation of Smaug wears on, its palette grows darker and its action scenes duller, while the introduction of an entire new crop of townspeople generates exasperation rather than immersion. (It doesn’t help that Ian McKellen, the film’s most human presence alongside the ever-dependable Martin Freeman, spends most of his meager screen time chained to a rock.) And although the initial encounter between Freeman’s Bilbo and the impressively engineered Smaug (voiced with delicious, palpable malevolence by Benedict Cumberbatch) is invigorating, the extravagant, interminable battle that follows is downright enervating, as Jackson’s camera cuts frantically back and forth across a half-dozen different dwarves whose names I can’t even remember. In the end, Jackson is so devoutly invested in killing bad guys—how many orcs are slaughtered in this movie? Does Orlando Bloom’s kill count reach quadruple digits?—that it’s hard to bother caring about the good guys.

More to come.

Previously in the Manifesto’s Review of 2013

The Worst Movies of 2013

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.