And at long last, Don Draper has died.

No, he didn’t fulfill a popular fan theory and jump out of his office building as pictured in the long-running opening credits. He didn’t die in the middle of a pitch, as his friend and mentor Roger Sterling had predicted. He didn’t die of lung cancer (though his ex-wife soon will). And, most mercifully, he didn’t get shot in the back of the head like what maybe happened to that other guy Matthew Weiner used to write about. But while the final scene of The Sopranos—the show on which Weiner cut his teeth, writing episodes as far back as 2004—will be debated pointlessly until the end of time, Mad Men‘s finale demonstrates the insignificance of that discussion. The Sopranos possibly ended with the death of Tony Soprano’s body. Mad Men concluded with something far more terrifying: the death of Don Draper’s soul.

That, of course, is just one interpretation. Undoubtedly, a pocket of viewers will insist that Don didn’t dream up the Coca-Cola ad that played this majestic series off the air, that he’s still meditating peacefully out in Big Sur, that the show’s final image of his lips curling into a smile proves that he finally found true enlightenment, not that he’d just experienced an epiphany on how to sell soft drinks. And maybe they’re right. Maybe that final chime wasn’t the sound of another lightbulb going off in Don Draper’s head, the instinctive response of a man who built himself into an executive of such towering potency—the man from the opening credits who tumbles from the top of a skyscraper, then suddenly reemerges, sitting confidently in his armchair—that he reflexively transforms human feelings into ad sales. Maybe Peggy wrote the Coke ad.

But I can’t accept that reading, because it doesn’t square with the Don Draper whom I’ve followed over the past seven seasons. That Don didn’t even start out as Don—he was Dick. But then a cigarette lighter collided with a puddle of fuel, and from the ashes sprang Don Draper, advertising genius. He knew he was living a lie, and he was forever haunted, not just by the terror of being discovered (recall the opening dream of the penultimate episode, when the cop bluntly informs Don, “You knew we’d catch up with you eventually”), but by the possibility that all of the monumental effort he’d expended to build his life anew was meaningless. “I took another man’s name,” he confesses to Peggy, his protégé and most faithful friend, “and made nothing of it.”

That’s a matter of opinion—Peggy vehemently disagrees, and if nothing else, Don fathered three kids with Betty, the oldest of whom is pretty awesome—but Don certainly believes it. It’s why he recently decided to repeat history and reinvent himself once more. These last few episodes of Mad Men involved Don stripping himself of the artifices that he accumulated upon his return from Korea. He quits his job. He gives his Cadillac to a hustler and admonishes him, “Don’t waste this.” He tracks down Stephanie, his de-facto niece, and offers her Anna’s old ring, a family heirloom. But he isn’t getting the rebirth he wanted; instead, he’s overwhelmed with grief and regret. “You’re not my family,” Stephanie spits at him, and the words are like a knife to the gut. Betty has already told him, quite accurately, that their children are accustomed to his absence, that his return home would only upset them. So, what now? If he isn’t Don Draper anymore, who is he?

Enter Leonard.

Now, every season of Mad Men has featured memorable monologues, but they’ve invariably belonged to Don, that artful manipulator of language. Whether he was filtering images of his home life through Kodak’s Carousel in “The Wheel” or revealing his impoverished origins to the Hershey’s execs in “In Care Of”, Don’s eloquent dialogue formed the backbone of Mad Men‘s biggest moments. But he was almost always talking, not listening. So it took some serious stones for Weiner to write one of his grandest, saddest speeches for the finale, then give it to someone we’ve never even met before. And while I can’t pretend that I expected a significant portion of Mad Men‘s final episode to take place at a California ashram, my bafflement proved unfounded once a soft-featured, middle-aged man shambled to an empty chair and started talking. As Leonard speaks—about how he’s invisible to his colleagues, about how his wife and children ignore him, and about his strange, vivid, metaphorical dream in which he’s an overlooked item sitting on a shelf in a dark refrigerator—Don finally achieves the catharsis he’s been searching for. This isn’t isolation, it’s kinship: another man living out his greatest fear of meaning nothing, of being nothing. Don breaks down and bear-hugs Leonard, and in that moment—the rawest and most vulnerable we’ve ever seen him—we sense that he might finally have broken through and found peace with himself.

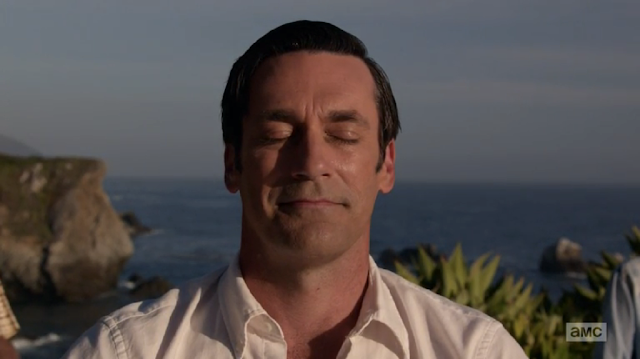

And that’s why Don’s final smile—beautifully sculpted by the great Jon Hamm—is profoundly tragic. He came so close to escaping the advertising world forever, but he got sucked back in by the vortex of his own creative talent, and his ego, and his inability to do anything else. “I want to work!” he memorably barked back in “Shut the Door. Have a Seat.” Turns out, that’s still true. This season, Don deprived himself of everything—his money, his property, his family—but he just can’t resist his own genius.

Still, even if this ending may be the wrong one for Don Draper (to be fair, that’s hardly a given), it’s the right one for Mad Men. If Don had actually reached nirvana on that remote beach, it would have felt like a cheat, a betrayal. He had simply built himself up too high to knock himself down. Yet it’s still a terrible irony. That relentlessly cheery Coke commercial is all bright sun and beaming smiles, but my own knowledge of its (fictional) genesis—of how it was made by a broken man who tried to heal himself by breaking, only to discover that he’d made himself indestructible—makes me deeply sad.

But there was, surprisingly enough, plenty of happiness to go around in the finale for the show’s subsidiary characters. Joan loses the impossibly selfish Richard, but she seizes the opportunity to build her own production company. Roger practices his French as he’s putting the finishing touches on his courtship of Megan’s mother, Marie Calvet. (Predictably, he also delivers the line of the hour in confessing his pending nuptials to Joan: “She’s old enough to be her mother. Actually, she is her mother.”) Meredith gets fired, but she’s confident that she’ll land on her feet, because she always does. (By the way, let’s acknowledge that Stephanie Drake absolutely crushed her part as Meredith; sure, she was ditzy, but she was also loyal, funny, and charming.) Sally assumes the mantle of motherhood, teaching Bobby how to cook and determinedly acting in her brothers’ best interests. Even perpetual grouse Pete Campbell seems to have a decent shot at reinventing his life in Wichita (his wife certainly seems pleased with the private jet). And then, of course, Peggy finally finds love, realizing that it was in front of her all along. The ultimate union between Peggy and Stan is one of the most conventional story beats Mad Men has ever delivered, but even if it felt a tad forced, I can’t begrudge Peggy Olsen a moment of romantic bliss.

But what about Don Draper? Is he happy? It hardly matters. This is simply who he is. He made himself, and he can’t escape himself. I find that heartbreaking, but I’m not sure Don would want it any differently. And hey, maybe in writing that Coke ad, he will finally find the happiness that has so long eluded him. But as a brilliant ad man once said, what is happiness? It’s just a moment before you need more happiness. Sadness, though? Sadness lasts forever. And so will Mad Men.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

great write-up

you nailed me!