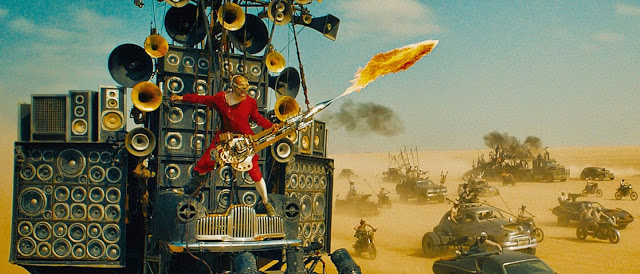

At various points in Mad Max: Fury Road—George Miller’s outlandish, unpretentious, frequently glorious action epic—an electric guitar suddenly reverberates on the soundtrack. It’s a playful sonic touch, but the musicality of the riff is beside the point; the real story is that the composer, Tom Holkenborg (credited here as Junkie XL), seems to be taking his cues from an actual character in the film, a red-clad, masked musician armed with the biggest double-neck six-string you’ve ever seen. Credited as Coma-Doof Warrior or the Doof Warrior (and played by the Australian instrumentalist iOTA), whenever he slashes his right arm across the strings, not only do bolts of noise blare on the soundtrack, but giant flames shoot out of the guitar’s headstock. And if that isn’t enough, the Doof Warrior spends his entire time riding on the roof of a massive 18-wheeler (the Doof Wagon, naturally) that’s barreling at top speed through the Australian Outback.

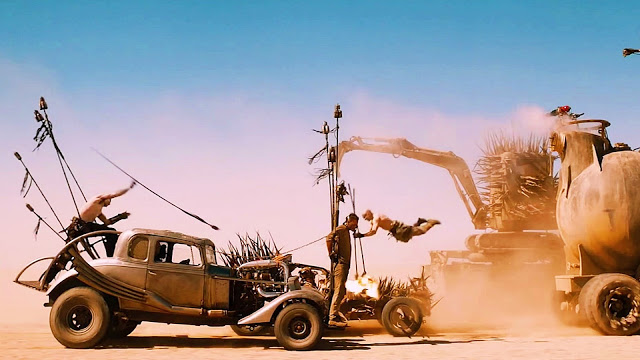

The Doof Warrior is the most memorable thing about Mad Max: Fury Road, but he is also the embodiment of its zany, carefree spirit. This is, after all, a movie that features a host of pursuing ATVs adorned with bristling spikes, resembling a motorized prickle of mutant porcupines. When bald, emaciated underlings aren’t sailing through the air on tall pieces of wood like demented pole-vaulters, they’re scrambling onto the hoods of speeding cars and spitting gasoline into open engines. Big rigs crash into one another, characters leap from vehicle to vehicle, and everything always seems to be on fire. (It’s hardly surprising that Verdi’s iconic “Requiem” figures prominently on the soundtrack.) Yet as crazed as Fury Road is, it is also lovingly intimate, the work of a director who cares deeply about his fictional dystopia. Miller may paint on an enormous, chaotic canvas, but he’s still an artist.

That’s crucial, because in the early going, Fury Road threatens to be overwhelmed by its own colossal scale. That’s especially problematic given the film’s general disinterest in human feelings. By that token, the plot—not that it remotely matters—is exceedingly straightforward. Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne, the main antagonist from the original Mad Max) is the despotic leader of The Citadel, a slab of quasi-civilization thronging with pitiable, starving slaves. As oil is the primary currency in this burned-out wasteland, Joe sends the one-armed Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron, in fine form) on a routine mission to collect gasoline. Furiosa, however, double-crosses him, spiriting away his quintet of trophy wives (whom he regularly impregnates) and revving her mammoth War Rig off in search of the mythical oasis known as the Green Place. As you might expect, Joe is less than pleased with this development, and he thus assembles his army—a band of stunted, pale-white zealots called the War Boys—and frantically pursues Furiosa.

And that’s pretty much it. Reduced to its barest essentials, Mad Max: Fury Road is basically one long car chase. The improbable feat of Miller’s filmmaking, then, is that he consistently dazzles viewers with both variety and clarity. The innumerable action set pieces on display here have undoubtedly received the aid of CGI, but they feel real, with a heft that marries the implausible to the physical. Not only does Miller’s camera coherently establish the geography of his demolition derby—that truck is about to ram this car, which will cause the guy clinging onto the car’s fender to fly into that wall of rocks, and squelch—but the film’s crisp sound mix and amazing stunt work combine to generate a tangible, convincing impact. Whenever something explodes—and something explodes quite often in this movie—you don’t just watch impassively. You feel the heat of the flames.

Nor is Miller’s artistry limited to automotive carnage. The production design of Fury Road is simply exquisite, especially in Immortan Joe’s acropolis, a sickly palace of intricate architecture and bizarre totems. It occasionally feels like a traveling carnival, replete with eye-catching grotesqueries: obese women lined up in rows like at a beauty parlor, dutifully pumping breast milk into vats; an immobilized dwarf peering through a telescope situated by a muscle-bound assistant; a man getting his pustules cleaned out before donning his armor. It may be icky, but it adds color and character. And while Miller’s screenplay, which he co-wrote with Brendan McCarthy and Nico Lathouris, is gratifyingly skimpy in terms of exposition, every frame teems with visual detail, suggesting a carefully designed universe that’s as meticulous, in its own debauched way, as the fastidious world of a Wes Anderson picture.

That’s why, although Fury Road is either a sequel to or a reboot of Miller’s Mad Max films from the ’80s (it really doesn’t matter which), its closest contemporary analogue is John Wick, the Keanu Reeves shoot-’em-up that abandoned traditional storytelling in favor of repeated gun battles and undeniable chic. But where that movie sported a dark aesthetic and dour mood, Mad Max: Fury Road is bright and triumphant. Its predominant color is orange, whether from the omnipresent flames or the billowing sand that chases characters across its arid desert. The costuming is equally impressive, especially the War Boys, who evoke childish vampires, at least until they suddenly spray their mouths with chrome and leap to their deaths like kamikazes. Miller’s characters don’t say much, but they sure look cool.

Speaking of characters, you may have noticed that I’ve yet to mention an angry fellow named Max. That’s because, outside of a quick prologue, our titular hero spends most of the movie’s first act silent, chained to a War Boy named Nux (Nicholas Hoult, having a blast), serving as the soldier’s “blood bag”. But once the film’s first extended chase scene finally concludes, Max enters the fray, though he nevertheless remains an enigma for some time. He rarely talks, he looks out only for himself, and he is one badass killing machine.

In other words, Max is the archetype of the lone Western gunman. But because he is played by the great Tom Hardy, he gradually exhibits glimmers of humanity and eccentricity, even as his brutish ferocity remains undisputed. (“You’re bleeding!” “That’s not his blood.”) Given Miller’s disdain for dialogue, Hardy communicates mainly with his eyes, but they say plenty, and his haunted demeanor—along with Theron’s gritty strength as the tough-as-nails Furiosa—attempt to give Fury Road a beating heart.

But it is not quite enough. The ostensible emotional center of the film involves the developing relationship between Max and Furiosa. Their first encounter certainly works like gangbusters; a frantic, bloody hand-to-hand fight, with Max still chained to an unconscious Nux, it’s Miller’s most inspired sequence, and there isn’t a single revved engine in earshot. Yet despite Hardy’s gruff charm and Theron’s steely toughness, the burgeoning friendship between the principals—unlike the rampant explosions that constantly surround them—never quite feels genuine. Miller is simply better at killing people than he is at caring about them.

That is a significant flaw, and it prevents the film from ascending to the pinnacle of action blockbusters. Fury Road is enjoyable, often immensely so, but it is not transcendent. Now, I appear to be in the minority; Fury Road has already achieved classic status, garnering rave reviews and soaring to #25 on the IMDb’s Top 250. I hate to pour cold water on the bonfire, but I feel compelled to voice my dissent: The movie isn’t that good. In fact, it isn’t really good at all. It’s allergic to character development, its threadbare plot is predictable, and its villain, while visually cool, is otherwise unmemorable. These are serious problems that do not dissipate simply because the movie happens to be regularly, staggeringly awesome.

But the thing is, Mad Max: Fury Road seems to know about all of these issues. It just doesn’t seem to care. It has no delusions of grandeur, and that, paradoxically, is what makes it grand. This is a movie that just rocks out and entertains, and it does so with both formidable technique and ample panache. It may not be very good. But like the Doof Warrior, in its flame-throwing bursts of maniacal genius, it can be wildly, improbably great.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.