There’s truth in advertising, and then there are the opening credits to Deadpool. Soundtracked to Juice Newton’s ’80s ballad “Angel of the Morning”, the camera pans and pulls slowly through a frozen still of interrupted carnage, and amid the suspended bullets and geysers of spurting blood, there peeks out a People Magazine cover. In that 2010 issue, People named Ryan Reynolds the sexiest man alive, so this would seem to be an opportune time for the title sequence to announce Reynolds’s presence in this madcap meta movie. Instead, the credits read, “Starring: God’s Perfect Idiot,” followed by other trivializing labels that summarize the remaining cast members: “a hot chick,” “a British villain,” “the comic relief,” “a CGI character.” The sequence concludes by informing us that Deadpool was produced by “asshats”, written by “the real heroes here”, and directed by “an overpaid tool”.

Is this anarchically funny or pitifully defensive? Who says it can’t be both? An ultraviolent superhero origin story filtered through the self-aware parody of send-ups like 21 Jump Street, Deadpool seeks to eviscerate the formula that pervades the Marvel Cinematic Universe while simultaneously hewing to that very template. (For the record, Deadpool is a Marvel production but is not formally associated with the MCU.) This means that it comes wrapped in a shield of protective irony that makes it virtually impervious to criticism. That is, how do you judge a pointless comic-book movie that so clearly knows it’s a pointless comic-book movie? Many MCU pictures are like schoolyard bullies, browbeating their mass audiences into submission through brute force. Deadpool is more like the class clown; accuse it of being stupid, and it’s likely to retort, “I know you are, but what am I?”

But even if Deadpool is fundamentally meaningless, it is not entirely witless. Much of its intelligence derives from the smirking charisma of its lead. Reynolds is indecently handsome, but his good looks have often obscured his performative skill; in undersung movies like Definitely Maybe, Adventureland, and Mississippi Grind, he has wielded his innate magnetism in subtle and surprising ways. Here, however, he’s in pure Van Wilder mode, but he’s still charming in his own cocky way, effortlessly firing off one-liners and never taking himself too seriously. The red suit may not suit him, but the character does.

That character is Wade Wilson, a mercenary who, when he isn’t thumping skulls, spends most of his time at a local dive bar run by Weasel (T.J. Miller, seemingly ad-libbing every line, with mixed success) and populated by a motley crew of beefy brawlers. (If you’re keeping score, Reynolds has actually played Wade once before, in the useless Hugh Jackman flick X-Men Origins: Wolverine; predictably, Deadpool lands a few well-placed jabs to the body of that misfire.) It’s there he meets Vanessa (Firefly‘s Morena Baccarin), a salty prostitute who, in addition to being similarly attractive, shares Wade’s taste for wordplay, foreplay, and other kinds of play that help lend Deadpool its well-earned R rating. All it takes is one highly charged game of skee-ball before these two are going at it, first in an alley, then between the sheets, and then seemingly on any flat surface.

And lucky for us. At the risk of deeming anything in Deadpool to be sincere, the coupling of Wade and Vanessa is one of the best romances the comic-book genre has yet produced. Reynolds and Baccarin have legitimately hot chemistry together, and their relationship seems rooted in genuine attraction, both physical and personal. There is something oddly disarming about a union where a heartfelt marriage proposal coincides with an equally heartfelt solicitation of anal sex.

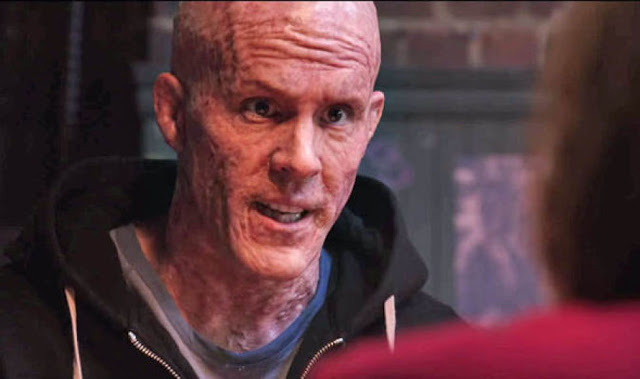

But Deadpool isn’t a love story, even if it should have been. It’s a superhero joint, with all of the mundane mayhem that entails. Wade gets diagnosed with cancer, and in a desperate attempt to defeat the illness, he submits himself to the care of Francis (a preening Ed Skrein, the original Daario Naharis on Game of Thrones), that aforementioned British villain who’s less a doctor than a maestro in torture. Agony ensues, buildings explode, and eventually Wade emerges from the flaming ruins with an invulnerable mutant body and a horribly disfigured face. (His heavily pockmarked visage provides considerable insult fodder for Weasel, who offers a number of unflattering metaphors, the most imaginative one involving Freddy Kruger and a topographical map of Utah—you can envision the featurette on the Blu-ray in which Miller trots out countless other improvised vulgarities.) Rather than subject passersby to his countenance, Wade dons the red suit from the comic, complete with twin katanas and a creepy mask (something about those egg-white eyes is deeply unsettling). He then sets out to hunt down Francis and consummate his quest for revenge.

Sounds familiar, right? Well, yes and no. Structurally, Deadpool is a thoroughly typical tale of superhero redemption, if one heightened with cartoonish violence and extreme brutality (think Kick-Ass but with actual mutants). But while the destination is inevitable, the journey is certainly different, with the screenwriters (Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick) constantly indulging in sardonic meta quips. When Wade visits Professor Xavier’s mansion from the X-Men films, he comments on the meager number of inhabitants—they include only Colossus (Stefan Kapicic), a hulking metallic biped, and Negasonic Teenage Warhead (Brianna Hildebrand, funny), a sullen teenager—and concludes that the studio must have lacked money. Some movies feature protagonists breaking the fourth wall; in Deadpool, Wade breaks the fourth wall while breaking the fourth wall, then analogizes this act to “sixteen walls”. And in lamenting his now-ugly appearance, Wade points out that his life is ostensibly over because, as we all know, nobody admires Ryan Reynolds for his acting abilities.

That last one is funny! But while Deadpool‘s one-joke premise generates a few laughs and a handful of wry chuckles, it also exposes its essential emptiness. It is not enough for a movie to simply identify a genre’s conventions. To be an effective parody, it must also provide its own contribution. Yet in exhuming the superhero movie’s tired tropes, Deadpool fails to fill in the resulting void with anything of substance or interest. The overpaid tool director, Tim Miller, serves up some perfunctory action sequences that are loud and busy but deficient in visual flair or filmmaking style. And despite the script’s insistent proclamations of irreverence, it can only sustain its sarcastic tone for so long before humor gives way to tedium.

It is hardly controversial to point out that many superhero productions are bloated and inane. But there are some good ones—Spider-Man 2, Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America: The Winter Soldier—that are motivated by more than just corporate greed. They want to bring joy to their fans, and they believe in the virtues of teamwork and heroism. Deadpool may mercilessly mock its cinematic brethren, but it doesn’t believe in anything. For a movie so smitten with the concept of irony, it falls victim to the same: In persistently poking fun at the soullessness of superhero movies, it reveals itself as soulless.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.