Arrival is a movie that asks a lot of weighty, philosophical questions—What does it mean to be human? How do our memories inform our sense of self? Are we alone in the universe? Are we alone with one another?—so let’s begin with a question typically asked of movies: What is it about? The answer, naturally, is a matter of perspective. From a literal standpoint, Arrival is an example of “hard” science-fiction, a piece of popular art that contemplates, with scrupulous discipline and serious pragmatism, what might actually happen if aliens suddenly appeared on Earth. That description is accurate, but it both over- and undersells the merits of this complex, thought-provoking film. On a deeper level, Arrival is a meditation on human connection, or lack thereof: the ties that bind us, the prejudices that plague us, our twin capacities for hope and fear. It isn’t about aliens. It’s about people.

That’s a lofty goal, and the challenge for Arrival, which has been directed by Denis Villeneuve from a screenplay by Eric Heisserer (based on a short story by Ted Chiang), is to fully explore its intellectual inquiries while simultaneously supplying frissons of drama and suspense. It’s a delicate balance that the film doesn’t always strike perfectly—it’s a little slow, and the integrity of the storytelling is occasionally compromised by a few one-dimensional minor characters. On the whole, though, Arrival is a consistently fascinating and sporadically transcendent achievement, the rare movie that demands being grappled with and argued about.

But getting back to questions, the first act of Arrival is preoccupied with just one: Why are they here? The “they” are alien spacecraft—shaped like giant obsidian eggs, a dozen have abruptly touched down across the globe, including one in Montana. (Their landing spots appear to be random; searching for a geographic pattern, the best scientists can come up with is a theory involving the popularity of Sheena Easton singles.) Understandably alarmed, the U.S. Army tasks a colonel (Forest Whitaker, inventing his own faux-Boston accent) with discerning the visitors’ nature and purpose. Because the arrivals don’t speak English (or any other recognizable language), the colonel recruits Doctor Louise Banks (an amazing Amy Adams), an expert linguist. Partnering with Ian, a theoretical physicist (Jeremy Renner, effortlessly likable), Louise endeavors to communicate with the aliens while the clock ticks constantly and anxious soldiers fidget with their trigger fingers.

The tension in these early scenes is stifling. Villeneuve is a filmmaker with serious thriller chops—his terrific Sicario was last year’s most nail-biting movie, while his brutal drama Prisoners was similarly agonizing—and he infuses Louise and Ian’s initial encounter with Earth’s newest guests with characteristic dread. An extended sequence where the scientists enter the darkened spacecraft through a narrow opening in its hull, like upside-down spelunkers leaping into a great maw, is grippingly disorienting, the camera warping our spatial perception to keep us off-kilter and on edge. Even when we meet the aliens, Villeneuve wisely shields them behind a translucent glass wall, lending their appearance—called “heptapods”, they basically look like oversized tree trunks with seven spindly legs—an aura of exotica. Bradford Young’s smoky cinematography makes excellent use of shadow and obfuscation, while Jóhann Jóhannsson’s throbbing score picks up where his music for Sicario left off, using dissonance and drone to amplify a deeply ominous mood.

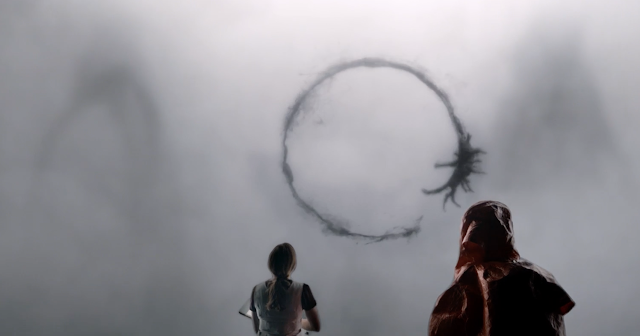

Yet for all its fraught uncertainty—and despite a heart-pounding sequence midway through the film that roils with Hitchcockian suspense—Arrival isn’t really a thriller. It’s more stimulating as a cerebral study of the unknown, if one that Villeneuve and Adams make far more exciting than you might expect. A sort of “What if?” for UFO enthusiasts, the movie plausibly depicts the collaborative efforts that a group of smart people might undertake to communicate with a foreign species. As Louise continues to interact with the heptapods, she gradually gains a rudimentary comprehension of their written language, an intricate form of coiled, circular finger-painting. Yet there’s still much work to be done, and in one geeky, fascinating scene, Louise diagrams the film’s predominant question—“What is your purpose on Earth?”—and then explains the myriad complexities involved in articulating that message.

Speaking of messages, Arrival has quite a bit to say, and the sheer breadth of its ambition is staggering. This begins with Louise. A plainly brilliant woman, she is also haunted by memories of her now-deceased daughter, the filmic repetition of which results in a sly piece of quietly ingenious misdirection. Shrewd plotting aside, as Arrival plays out, it becomes less of a conventional sci-fi flick and more of a poignant character study, with Adams’ fiercely intelligent and nuanced performance making Louise an achingly vulnerable vessel of loss and compassion. Even as Heisserer’s screenplay traffics in heady concepts like the nonlinear nature of time—the movie’s helix-shaped structure will draw comparisons to Christopher Nolan’s majestic Interstellar—Villeneuve and Adams make certain to tether these brainy conceits to Louise’s own personal struggle.

But even beyond this, Arrival is something else: a blunt, unapologetic, genuinely moving parable. The predicament that its characters face is global, not local, and during the course of the film, they routinely converse with leaders from other nations on a bank of television screens, sharing data and discussing next steps. Yet as the movie’s pace quickens and its tone darkens, many of those screens go blank, resulting in an isolation that seems destined to lead to disaster. In this, Arrival posits a nigh-religious conflict, pitting humanity’s most munificent instincts—tolerance, openness, generosity—against its bleakest impulses—mistrust, entrenchment, xenophobia. (Where Louise embodies the former, the latter are given voice by an enjoyably officious Michael Stuhlbarg.) As Louise recognizes, only through the basic virtues of decency and empathy—only by pursuing harmony rather than spreading discord—can our planet’s cultures work together to forge a way forward. It’s almost like it has nothing to do with aliens at all.

You may be tempted to disparage this allegory as obvious, cheesy, sentimental. What’s the point of lauding the qualities of open-mindedness and understanding when no one could reasonably oppose them? To which I would counter: Have you seen the news? Arrival would be a meaningful picture regardless of its release date, but it feels especially urgent in light of the presidential election, a cycle of ugliness that has normalized hatred and kindled fear. As we move into a new political era—one that is likely to bring about seismic changes in terms of immigration, foreign affairs, and countless other issues—it is heartening to watch a movie that argues so persuasively for the inherent kindness of the human race.

In relaying the scope and weight of its vision, Arrival is breathtaking, but it isn’t uniformly satisfying. I confess that the literal part of my brain craved greater clarity and resolution (a third-act twist, though powerful in retrospect, is a bit fuzzy in the moment), while the genre enthusiast in me longed for more of the blasts of excitement that Villeneuve brought to Sicario.

But entertainment is not this movie’s primary goal. This is not to discount its pleasures: Arrival looks and sounds great, and any time spent with Amy Adams is a gift. Still, there’s more going on here than strong storytelling and exquisite craft. Not unlike the creatures it portrays, Arrival is an unusual species: a mainstream studio movie with something to say. And as the final leg of Louise’s journey makes painfully, beautifully clear, we would be remiss not to listen.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.