It is an unwritten rule that every movie set in space must feature a scene where a character suddenly begins to run out of oxygen. Passengers, the diverting, flawed, occasionally fantastic romantic thriller from Morten Tyldum, is no exception. But the scene in question, which is both exciting and exasperating, arms critics with an all-too-apt metaphor to describe the broader film. Here is a movie that begins with enormous promise, sustains that promise for well over an hour, and then slowly, steadily runs out of air. It gasps for breath, its limbs flail helplessly, and its brain, deprived of precious nutrients like logic and plausibility, shuts down.

But if I’m writing less of a review than an obituary, allow me to express the hope that Passengers—which has been unjustly savaged by critics—may rest in peace. Its ultimate demise should not invalidate the genuine delight and intrigue it provided while it was still alive. By which I mean, for its first two acts, Passengers is a whole lot of fun. Visually, it’s sleek, sharp, and sexy, with a slick, antiseptic production design, fetching costumes, and a pleasing color palette. And narratively, it tells an engaging story fraught with genuine moral conflict. A high-concept sci-fi think-piece, it will undoubtedly draw unflattering comparisons to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but it’s inspired less by Kubrick than Kieslowski, and if its answers to its philosophical quandaries are less than satisfactory, it at least has the courage to pose such dilemmas in the first place.

Not unlike Alien, Passengers opens with a roving shot of its central spaceship, the Avalon, a lithe, spidery vessel carrying 5,000 sleeping travelers. As Thomas Newman’s score flares ominously (the composer borrows heavily from his darker cues on Wall-E), the Avalon’s autopilot rumbles head-on into an asteroid field. This being the distant future, the ship automatically repairs its damage, with the exception of a single hibernation pod, whose malfunction leads to the waking of Jim Preston (Chris Pratt). Groggy and disoriented, Jim numbly follows the cheery directions of a holographic assistant, tumbling into his assigned sleeping quarters without much thought to his surroundings. Only the following morning does he realize that, hey, it’s awfully quiet around here.

Yeah, about that: Turns out that the Avalon is in the midst of a 120-year journey to a colonial planet called Homestead II, and it still has 90 years to go; Jim was inadvertently woken a rough century ahead of schedule. He is unable to rouse any crew members or contact anyone back on Earth, and while he is (conveniently) a mechanic, the complexities of hibernation technology—and the laws of cinematic plotting—render him incapable of going back to sleep. This means that he’s destined to live out the rest of his life by himself on the Avalon, a prisoner trapped on the galaxy’s longest, loneliest cruise.

This is undoubtedly bad for Jim, but it’s good for us. Tyldum and his screenwriter, Jon Spaihts (Prometheus, Doctor Strange), don’t shy away from the tragedy of Jim’s existential predicament, but they also mine it for some clever black comedy. Some of this comes from Arthur (Michael Sheen, funny), a bartending android who serves Jim whiskey, politely listens to his grievances, and dispenses clichéd advice. Some derives from Jim’s decision to attempt to ignore his eternal doom and instead enjoy his new digs, which include a high-tech basketball court and an interactive dance studio. (If nothing else, Passengers is indisputably one of the two best movies in the past three years in which Chris Pratt engages in an interstellar dance-off.) And some arises from the Avalon’s litany of robotic helpers, who initially ground the film as a light satire of the customer-service industry. Jim is surrounded by smiling holograms and pleasant-sounding operating systems, each of whom is singularly incapable of grasping his unique difficulty. At one point, in a moment that will surely earn the sympathy of anyone who’s ever tried to telephone Dell or Comcast, Jim howls at a machine, “I need to talk to a person, a real, live person!”

Does he ever. As time passes, Jim’s isolation grows more pronounced (he eventually sports a hideous beard), his routine more dreary. He longs for companionship. He longs for human connection. He longs for, say, someone who looks like Jennifer Lawrence. And would you believe it, one day, Jim—in the throes of suicidal depression—glimpses a hibernation pod that houses a lovely woman named Aurora, and he wonders whether he just might use his mechanic’s skills and wake her up.

Now, I do not pretend that Passengers will immediately enter the philosophy curriculum at Harvard. And some viewers will surely be mortified by the film’s mere suggestion that Jim is faced with a legitimate moral conundrum. But to the immense credit of both Tyldum and Pratt, Passengers manages to make Jim’s swelling obsession with Aurora appear to be something other than completely creepy. The key is the pacing: We spend sufficient time with Jim to appreciate the enormous weight of his pain, which makes it more credible when he contemplates doing something so drastic. Pratt, an effortlessly appealing actor, helps sell Jim’s mental agony, a mixture of yearning and self-loathing. And whereas most people rely on friends or family to disabuse them of their extreme ideas, Jim has nobody around to talk him out of waking Aurora. (One of the film’s funniest scenes occurs when Jim seeks advice from Arthur, who responds congenially, “That sounds like a fine idea—you could use some company.”) In space, no one can hear him scheme.

And really, what would you do? Could you possibly be so selfish as to rob another person of her future in order to salve your own anguish? Would the prospect of a lifetime of utter solitude sway your thinking? And have I mentioned that Aurora—whose very name echoes Sleeping Beauty—is played by Jennifer Lawrence?

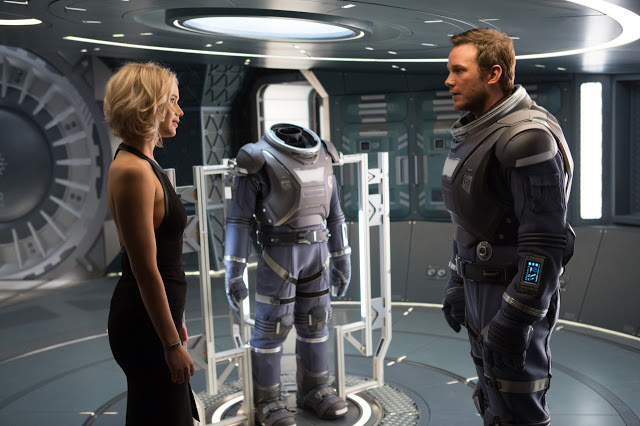

It is hardly a spoiler to reveal that eventually, whether by Jim’s hand or another’s, Aurora rises from her pod like a goddess. And at that point, Passengers suddenly and joyfully transforms into a silky, sudsy romantic comedy. It is inevitable that Jim and Aurora fall in love—they are, after all, the only two people in their cloistered world—but even if neither character is especially three-dimensional, the actors depict their mutual attraction with enthusiasm and sincerity. Pratt has the trickier part, but his measured approach contrasts nicely against the fiery Lawrence, who strives to deliver an emotional, go-for-broke performance and (as usual) nails it. Jim and Aurora’s fumbling first kiss, complicated by the fact that they’re both wearing bulky space suits, is simply adorable, while a scene where Aurora impulsively clambers across a breakfast table to tear Jim’s clothes off is the height of giddy, lovestruck fantasy.

Sadly, all fantasies are fleeting, and when Passengers transitions once again—this time into a breakneck, man-vs.-nature actioner—it does so with a thud. Tyldum has proven himself a fine director of both human dramas (The Imitation Game) and gritty thrillers (Headhunters), but here he lacks the vision to execute his set pieces with any real flair. This makes Passengers‘ more hectic moments feel like, well, an imitation game, a faint echo of other, more impressive science-fiction pictures. A sequence featuring a spacewalk and a snapped tether feels like a deleted scene from Gravity, while a climactic surgical operation in a cylindrical healing chamber recalls That Scene in Prometheus. (The exception to this sense of duplication is a stunning sequence—scientifically dubious but nevertheless heart-pounding—in which a soothing late-night swim turns into a frantic fight against zero-gravity.) Beyond that, Tyldum fails to invest his characters’ frenzied tribulations with the requisite spatial and narrative coherence. For the film’s final half hour, Jim and Aurora are constantly scurrying to and fro, agitatedly performing technically imposing tasks (vent the reactor! shut down the containment field!); it’s meant to be suspenseful, but because everything is so thinly sketched, it just comes off as silly.

It’s a bummer. Yet the failings of Passengers must be viewed in context. In a sense, the movie serves as a referendum on how to evaluate movies. Some viewers may be so repulsed by the stink of the film’s finale that they will allow it to sour the considerable pleasures that preceded it. I’m less inclined to be so severe. Part of this is somewhat selfish; here is a big-budget feature based on an original screenplay, the kind of ambitious picture that I hope studios will continue to make. But part of it is the simple recognition that endings aren’t everything—movies are far too multifaceted to be judged solely on the strength of their conclusion. And Passengers, for all its third-act faults, is by and large an enjoyable cinematic experience, full of beauty and romance and wonder. The destination may be a letdown, but the journey is a trip.

Jeremy Beck is the editor-in-chief of MovieManifesto. He watches more movies and television than he probably should.

Beale and I just saw it. We judged it much the same way you did! Although I was clutching his hand and pulled in by the suspense of the last act, whereas Beale was less thrilled. I thought the worst part of the movie was Lawrence Fishburn, thanks to awkward acting and a bad script. Enjoyed the rest of the ride though 🙂 great review! Love your last sentence.